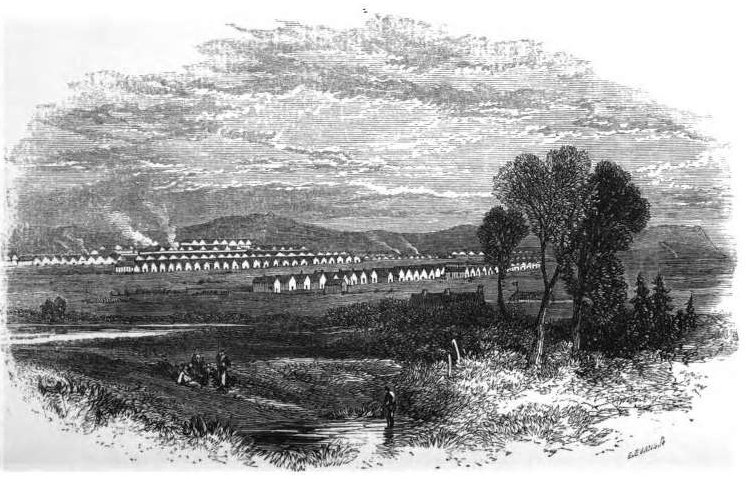

A General View of the Camp at Aldershot, from a sketch by Marianne Young (facing p. 21). Prince Albert, an "armchair strategist" and a stickler for organisation, felt that the British army compared badly with the continental model, and wrote to the Duke of Wellington in 1847 "proposing a provisional training camp for the army" (Stewart 153, 158). Such a facility was set up in 1852 in Chobham, Surrey, but it was only a short-term solution, and did not satisfy him. At last, he persuaded the government to acquire 3000 acres of sandy heathland at Aldershot, on the Hampshire/Surrey border, for a permanent base. The camp was laid out in the mid-1850s, with bell-tents quickly giving way to wooden huts, which were later replaced by brick ones. From the beginning it was divided into north and south sections, their blocks lettered alphabetically. The south was larger than the north, with accommodation for 12,000 men, while the north, on the other side of the Basingstoke Canal, housed only 8,000 (see Young 26). In 1858, the road links with London and Portsmouth became less important with the opening of North Camp station, which then had "four broad platforms, designed to help troops entrain and detrain" (Holmes 512; only two platforms remain now).

The Queen's Pavilion, from a sketch by Young (facing p. 82), who found "its form and position highly suggestive of an Indian bungalow" (24).

Having urged this permanent encampment, the Prince continued to support it, pushing for the full reorganisation of the army. In 1855, for instance, he wrote a long memorandum to Lord Aberdeen, pointing out problems in the way the army operated: "We have ... no generals trained and practiced in the duties of that rank ... no general staff or staff corps ... no field commissariat, no field army department, no ambulance corps, no baggage train...." (qtd. in Stewart 156). Perhaps equally important in promoting change was the way he encouraged "the increasingly personal interest of the Queen herself" (see Mallinson 217). In this endeavour, he oversaw the design of a pavilion, recorded as having had "graceful timberwork, looking oddly like C20 Scandinavian and an impressive testimony to Prince Albert's modernity" (Pevsner and Lloyd 826), which the royal party could use when reviewing the troops. He also ensured that it was visited regularly:

Often ... the long valley presents a brilliant aspect, when her Majesty and staff review the troops. Early in the season, when the militia were stationed in the south camp, it was pleasant to note these thousands of the sons of the soil, who had never before seen their Queen, march by the little knoll on which she stood, her richly-caparisoned charger by her side; to watch their eager glances and gratified smiles, with the difficulty they evidently had to remember that they were soldiers, and so not free to express their rough enthusiasm; it was amusing to see the country-squire captains, and some of the marvellously stout surgeons, fresh from private practice, try to affect the military bearing that only comes of twenty years' service. (51-52)

Sadly, the pavilion was demolished in the 1960s when the barracks were rebuilt, and replaced by a training school for the Royal Army Nursing Corps, completed in 1966 (Pevsner and Lloyd 74). The site now houses a huge computer science complex, though the name remains, as the address is still "Royal Pavilion."

Left: An officer's hut (still wooden here). Right: Interior of the hut.

Both taken from sketches by Young, facing p. 30. Young explains that the room is "furnished by an enormous coal-box, of the dimensions of an ordinary bath," and observes that the grate is "also singularly out of proportion to the apartment." Furniture consisted of "a small iron bedstead, with a camp chair and table. The chief decorations of the walls are a cap, sword, and cloak, and although from the adjoining apartment may be heard the voice of an Irish help, or a crying infant ... , one cannot help feeling that domestic life is out of place here" (29-30).

Barracks had now taken over from the old system of billeting, but they were notoriously spartan: "Barracks were long draughty rooms with primitive sanitation," writes one modern commentator succinctly (Nalson 4). Even these single rooms for officers look bleak and confined, especially considering that the occupant would probably have come, if not from the aristocracy, then from "the upper section of the middle class" (qtd by Holmes 161, from a comment of 1858).

Young herself concedes that the whole place could look perfectly "dismal," but she also conveys something of the excitement of living in the army:

It is scarcely possible to imagine any spot of earth so dismal as the camp of Aldershot on a field-day — the black, tenantless huts; the roads, long, bare, silent; the poor cur, who here and there wanders forth, weary of the solitude; the single tradesman's cart, stopped at a corner, the driver sleeping, no one being there to receive his goods; the hospitals, with their sentries, and the poor men in blue, looking to the distance, and feeling how weary a thing is pain and weakness: but at mid-day, hark! they are coming lack. The familiar airs sail nearer and nearer on the breeze: from the rising ground the red threads wind along, some branching to the north, others coming onward to the south; they halt — all is line and order for a moment — it is past, and then the whole plain is covered with men, each soldier, with his musket in his hand, running quickly to his hut; when freed from his heavy weapon, he may seek the cook-house, eat, drink, and be merry. (Young 63-4)

Left: One of the original brick-built barracks now being used as part of the Aldershot Military Museum. Right: The Prince Consort's Library. Prince Albert himself financed the library that still bears his name, for the further education of the men in military matters. It still "supports the work of the Army and the wider defence community" ("Prince Consort's Library").

The Crimean War was a wake-up call for those directly involved in army matters, making it painfully clear to others besides Prince Albert that the army had to be put on a more professional footing. The process itself was a long one. However, the prince's input was valuable, and the establishment of Aldershot Military Town was an important step in the right direction.

Related Material

- The Role of the Victorian Army

- The Prince Consort's Library, Aldershot

- The Prince Consort and His Legacy (a review of Jules Stewart's Albert: A Life)

- Royal Garrison Church of All Saints, Aldershot

Bibliography

Holmes, Richard. Soldiers: Army Lives and Loyalties from Redcoats to Dusty Warriors. London: HarperPress, 2011. Print.

Mallinson, Allan. The Making of the British Army from the English Civil War to the War on Terror. London: Bantam, 2009. Print.

Nalson, David. The Victorian Soldier. Oxford: Shire, 2000. Print.

Pevsner, Nikolaus, and David LLoyd. Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Buildings of England series. London: Penguin, 1967. Print.

Prince Consort's Library. Leaflet available at the library. Print.

Stewart, Jules. Albert: A Life. London: I. B. Taurus, 2012. Prnt.

Young, Marianne. Aldershot and All About It, with Gossip, Literary, Military, and Pictorial. London: Routledge, 1857. Internet Archive. Web. 13 May 2012.

Last modified 13 May 2012