[This document comes from Helena Wojtczak's English Social History: Women of Nineteenth-Century Hastings and St.Leonards. An Illustrated Historical Miscellany, which the author has graciously shared with readers of the Victorian Web. Click on the title to obtain the original site, which has additional information.]

Sarah, Countess of Waldegrave was without doubt the most influential woman in nineteenth-century Hastings. She was born Sarah Whitear, a clergyman's daughter, at Hastings Old Town Rectory in 1787. Her first marriage was to Edward Milward, many times Mayor of Hastings, and on his death she inherited great wealth. Her subsequent marriage to an earl made her a Countess.

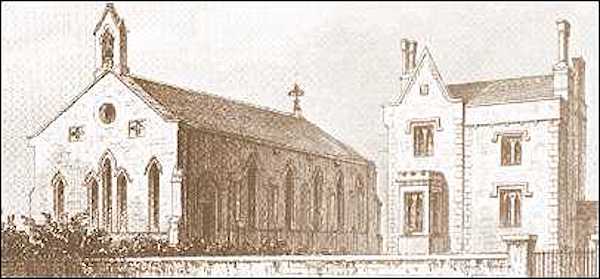

Sarah used her position and wealth to help the town and, most especially, the poor. She endowed seven churches. The first, in 1838, was St Clement's, Halton (pictured below) for which she donated the site, the building stone, the school and the parsonage. She funded numerous Sunday schools, poor schools, and institutions, and provided wash houses and public baths for the poor in Bourne Street. She also funded a Fisherman's Institute in All Saints' Street and was involved in the Hastings Literary and Scientific Institution.

A bossy and autocratic woman, Sarah did not hesitate to interfere and to persuade people to do things her way; which of course they did, especially as she often attached strict conditions to her gifts. She financed a school in the High Street on the condition that there were separate girls' and boys' entrances; she allowed public access to Ecclesbourne Glen and the Lovers' Seat, but would not allow any alcoholic beverage to be sold there.

St Clement's Church and parsonage, Halton. Detail from an 1849 engraving. The church was demolished in the 1970s.

Pennies were collected from the town's children to erect a drinking fountain to her memory. This was built in 1861 and stands outside Holy Trinity church, Hastings. In 1865 John Bazalgette called it "one of the prettiest drinking fountains in England, I know nothing to compare to it for architectural beauty and good taste." However, he continued:

Its condition, as I have seen it, is disgraceful. It is dirty, and, unfortunately, in its state of dirt, IT IS DRY... devoid of that source of health it was intended to convey, in order to relieve the poor man from the compulsion to visit the public-house and its consequent drunkenness. (Hastings & St Leonards News, 22 September 1865)

Last modified 2000