Introduction

In the midst of fog-filled Victorian nights, patient parents would soflty whisper lullabies to their sleepless children, soothing their fears that a monster might be loitering under their bed. Little did they know a particularly dangerous monster was hiding in the dark cracks of the etymology of their consolation: some argue that the word 'lullaby' is derived from the Hebrew 'Lilith abi', which signifies 'Lilith, begone' (Gorrell 100). The origins of the demoness Lilith can be traced back to the dawn of monotheist cults; according to the Jewish Talmud, written during the second century, she was Adam's first wife, created equal to him unlike his second wife Eve, who was designed as his obedient partner. After refusing to adopt the submissive position during sexual intercourse, she was banned from the Garden of Eden, sent to Hell, and doomed to see every one of her children die. According to one legend, she morphed her body into that of the snake Nahash in order to tempt Adam's new wife Eve into her downfall.

Over the centuries, her character suffered the reputation of a snake-like child-eater, and a sexually alluring temptress for men (Patai 296). Lilith's tragic figure, which always lingered in the confined circles of Talmudic and Jewish oral histories, and loitered in the shadow of the Middle Ages and early modern era, far from the light, arguably because of the Christian hegemony of the period in Western Europe. Nevertheless, Lilith slowly crept her way into the general subconscious of Victorian society, where she shifted from a blood-thirsty therianthrope to an alluring femme fatale, due to different cultural and religious factors.

The first occurrence of Lilith that transcends ancient religious texts into Western European folklore appears in Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe's masterful 1808 play Faust, where the succubus was introduced as Adam's first wife, a woman of great beauty — a danger against whom Faust is warned. John Keats shyly introduced the figure into nineteenth-century Britain with his Lilith-infused poems “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” (text) and “Lamia” (the Roman translation of the name Lilith), in which dangerous temptresses lured men to the depth of despair. The works of Goethe and Keats started the process of Lilith’s transcendence. She gradually obtained not only a physical body, but also one with a sensuous appearance. In doing so, Lilith established herself as a catalyst of several major Victorian anxieties through her rising transformation and mystification.

Faust and Lilith (Faust preparing to waltz with the young Witch at the Festival of the Wizards and Witches in the Hartz Mountains). Richard Westall. Oil on canvas. 1831. Courtesy of Langan's Restaurant, London.Arguably, the first depiction of Lilith in nineteenth-century art was executed by Queen Victoria's drawing master Richard Westall’s depiction of the encounter between Faust and a seductive Lilith in his piece Faust and Lilith (1831). In this painting, Lilith had all the features of an English rose, with her lily-white skin, red hair, fine features and voluptuous body leaning towards Faust; she captivates him with the delicacy of her traits and curves of her body amidst a scene of debauchery. Beyond the beauty, Faust fatally fails to see the face of Satan frowning at him, and the small serpent crawling towards him; this depiction of Lilith embodies sensual temptation in its purest form, as it leaves Faust blind to anything other than the feminine ideal. For the first time, Lilith fully lost her bestial side, for the snake is present in the painting but not as part of her anatomy. She is fully human and humane, virginal-looking yet deadly attractive.

The Importance of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood on the establishment of Lilith as a Victorian Icon

After Westall's glorious introduction, Lilith had to wait almost half a century to reappear on the Victorian scene, and to be established as an icon by the Victorian Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a creative, dissident group that emerged from the artistic circles of the Royal Academy in the late 1840s. With Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt at its founding core, the Brotherhood founded its basis in the belief that art was meant to be moral, innovative, politically reformist, and should follow the masters of painting pre-dating and up to Raphael (Barringer, Rosenfeld, Smith 9). Biblical, mythological and literary themes were prevalent and preferred amongst the group, and more particularly the female figures of those narratives. Proserpine, Beatrice Portinari, Salome, Ophelia, the Lady of Shalott, and more strong feminine figures have been the subject of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's soft and bright oil paint brush strokes.

Lady Lilith. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Oil on canvas. 1873. Courtesy of Delaware Art Museum.

Rossetti, one of their most prominent members, found himself attracted to the work of Goethe, and established Lilith as a Victorian icon by means of what could be considered a truly creative obsession. His painting Lady Lilith presents a voluptuous, warm-toned depiction of the succubus brushing her copper hair, a halo of lush flora surrounding her. Her diaphanous beauty can only indicate the influence of Westall's painting on this figure, but unlike the first picture, this image of Lilith seems more suggestive, as her sensuality is only revealed by the focus on her naked shoulder, emphasised by her fully clothed body. The centre piece of the painting is undoubtedly her hair, the embodiment of a dangerosity and sensuality she embraces: indeed, the comb and mirror are the focal point, affirming her narcissistic and body-orientated inclinations. Notable elements framing the painting deserve to be highlighted: the white roses surrounding her hair like a halo have most commonly been associated with the symbolic ideas of virginal beauty, purity, and innocence, whilst the poppies at her elbows have been ancestrally used for the extraction of deadly opium. The association of these two metaphors establishes a contrast between the innocent and the lethal, and adds ambivalence to the character; she stands somewhere between nobility (Rossetti ennobles her with the title of 'Lady') and disrepute.

Rossetti also touched upon the beauty of the corporeal in his sonnet “Body's Beauty” composed in 1881, paralleling his painting to offer an interdisciplinary representation of his Lilith:

Of Adam's first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

That, ere the snake's, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative,

Draws men to watch the bright web she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

The rose and poppy are her flowers; for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

Lo! as that youth's eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

This sonnet embodies all the ambivalences of the painted character; the themes of the poppy and the rose are once again touched upon, as well as the importance and emphasis on Lilith's hair as her seductive weapon. She is depicted as a witch flaunting her reptilian tongue between 'soft-shed kisses'. Nevertheless, Lilith appears more overtly deadly in the sonnet, as she takes the life of an enthralled young man in the last two lines, perpetuating her reputation as a femme fatale. In a letter to his friend Dr Hacke in 1870, Rossetti referred to his picture-sonnet as the representation of a 'Modern Lilith' (Allen 286). This modernity, according to Virginia M. Allen, had a lasting influence on the new representation of Lilith for a modern audience: 'Rossetti may have delved into his capacious memory for Goethe's image, but his involvement with the form was perennial. It was with this work that the image received a new label, and the deadly night-demon of Jewish folklore received a new form' (291). This painting was therefore a defining landmark for the depiction, appreciation and evolution of Lilith, as she became even more beautiful and ambivalent, therefore more menacing.

Lilith. John Collier. Oil on canvas. 1887. Courtesy of Atkinson Art Gallery.

Rossetti's work inspired another Victorian artist, John Collier, to paint one of his most famous pieces, Lilith, in 1887. His Lilith bears a striking resemblance to Rossetti's Pre-Raphaelite style, with her luscious red hair, angelic resting face (rendered in tempera painting technique); she nevertheless appears more sexually menacing. A snake is wrapped around her naked neck, hips and leg, gently brushed by her long hair. In a movement of seduction, she reveals her neck to the snake, its fangs seemingly ready to plunge her into deceit - or into confidence. The contrast between her light white body and the darkness surrounding her diffuses a sense of dread and uneasiness, as the fragility of the delicate young woman hides a darker tone. In the same fashion as Westall's Lilith, her alluring nudity 'is not overly lascivious, and Lilith is presented as an image of idealised beauty, which is both realistic and contemporary.' Indeed, Lilith was again given a modern twist as she was adapted for Victorian British beauty ideals, similarly to Rossetti's Lady Lilith, with her long red hair, pale skin, and curvaceous figure.

Following Westall's tradition, Lilith was assuredly established within Victorian iconography thanks to Rossetti and Collier's paintings, as in both paintings she represented the anxiogenic dichotomic beauty surrounding the Victorian female body, in both its virginal and tempting splendour. Both Pre-Raphaelite artists offered a modern take on Lilith and reassessed the character's dangerous femininity; even if the snake is still present, she is detached from it in a corporeal sense, and presented as an unambiguous aesthetical British ideal. Her ambiguity shifted from snake-human to virgin-temptress, as her dangerousness became more subjugated yet just as strong.

An evolving vision of femininity and womanhood

This shifting perception of a character as dominating as Lilith into a modern and attractive depiction took hold of the Victorian arts as the condition of women was drastically changing. In the beginning of the Victorian era, the demands of the Industrial Age needed women to participate in labour, but they were confined to domestic roles at home, and their social status only valued by their relation with a masculine relative, as they did not have to right to own properties or vote. Roderick F. McGillis analysed 'the limitations of Victorian domestic life where fortunate women married and bred, the less fortunate found positions as cooks, governesses or maids, and the least fortunate drifted to the streets' (McGillis 3). Nevertheless, in the beginning of the 1880s, the image of the New Woman, an emancipated, free, and intellectual Victorian woman started to emerge in English society, in light of the rise of the suffragette movement, and the feminisation of education and labour (Diniejko). Intellectual feminists such as Mrs. Wolstenholme Elmy, and her ally and friend Emmeline Pankhurst became the leading figures of a changing social order, advocating female empowerment and free love through franchise in the late nineteenth-century. The fin-de-siècle became a key period for the advancement of feminism, as considerable milestones were reached for the improvement and evolution of the female condition. In 1869, nine women sat through the “General Examination for Women” in London, and six of them became the very first women to access university education in England (Carter). Lilith, the child-eater and sexual temptress, therefore came to metaphorically and exaggeratedly represent this new vision of femininity, between female empowerment and danger for the traditional social and family structure. As Virginia M. Allen puts it into words: 'She represents the New Woman, free of male control, scourge of the patriarchal Victorian family' (Allen, 286). The image of the free temptress was still at the core of the character, her alluring and tempting figure, bedroom eyes and luscious hair remaining the features of sexual danger, fitting her in the label of the emasculating femme fatale, halfway between the “Madwoman in the Attic” and the “New Woman”.

The anxiety Lilith stirred within Victorian society can nevertheless not be only attributed to her embodying the New Victorian Woman; Lilith provoked an uncomfortable anguish for her transcendence of feminine labels. Depicted in very intimate and tranquil scenes -naked, combing her hair in front of a mirror- and bearing the features of a traditional English lady, the paintings show Lilith as an aesthetically tamed and pure woman which seems to stay indoors, with her lily-white skin; her physical appearance emanate an immaculate aura, as opposed to past monstruous and anxiogenic depictions. This aesthetical conflict has been identified by Nina Auerbach: 'It may not be surprising that female demons bear an eerie resemblance to their angelic counterparts, though characteristics that are suggestively implicit in the angel come to force in the demon' (Auerbach 75). While depicted as a monster in the Talmud, she now appears as a woman of good repute in English arts; the unresolved tension between the appeal of a respectable woman and the abject attraction of a temptress undoubtedly unnerved Victorian audiences.

This depiction of Lilith as an influence on fin-de-siècle Victorian literature

In addition to Victorian pictorial art, Lilith made her way into the lines of some of Britain's best authors. Among them, Robert Browning and George Macdonald possibly delivered the most brilliant literary depictions of Lilith.

In 1883 Robert Browning composed “Adam, Lilith and Eve”:

One day, it thundered and lightened.

Two women, fairly frightened,

Sank to their knees, transformed, transfixed,

At the feet of the man who sat betwixt;

And "Mercy!" cried each--"if I tell the truth

Of a passage in my youth!"

Said This: "Do you mind the morning

I met your love with scorning?

As the worst of the venom left my lips,

I thought, 'If, despite this lie. he strips

The mask from my soul with a kiss--I crawl

His slave,--soul, body, and all!'"

Said That: "We stood to be married;

The priest, or some one, tarried;

'If Paradise-door prove locked?' smiled you.

I thought, as I nodded, smiling too,

'Did one, that's away, arrive--nor late

Nor soon should unlock Hell's gate!'"

It ceased to lighten and thunder.

Up started both in wonder,

Looked round and saw that the sky was clear,

Then laughed "Confess you believed us, Dear!"

"I saw through the joke!" the man replied.

They re-seated themselves beside.

It presents the first instance of a bonding friendship between Lilith and Eve, as they are first introduced as 'two women', speaking the same words to their Adam. It is the most sympathetic and less threatening representation of the demoness; she swears that 'the worst of the venom left my lips', as she professes her desperate love for Adam, and bears no cruel feelings towards the original couple. We are in fact presented to a shifting opposition, as Lilith and Eve seem to form a pair in front of Adam, contrasting with the canonical couple of Adam and Eve against Lilith. Browning did not restrict his depiction of her with a mere physical description: he went into the depths of his interpretation of the character, depicting the desperation of a loving woman: 'I crawl / His slave, --soul, body and all!'

George Macdonald’s 1895 masterpiece Lilith returns to a more traditional portrayal of Lilith, with her canonical demoniac traits. The novel tells the story of Mr Vane, an Oxford graduate librarian who discovers the passage to a parallel universe where his father resides with the help of a ghost, Mr Raven. There, he meets Lilith, the Queen of Hell, who seduces him. She stays a seductress, and reappears as the child-killer she is; the reader is introduced to her daughter Lona, whom she ends up killing, before being brought to the House of Death. Once again, Lilith appears as a femme fatale, burdened with the discomfort she triggered in audiences: “one feature of MacDonald's Lilith is the concurrent pity and repulsion which she attracts. Lilith has all the ingredients of the fatal woman as outlined in Mario Praz's The Romantic Agony: she is timeless, wise, troubled, and pale” (McGillis 8). MacDonald also repeated a Talmudic episode in the chapter “To the House of Bitterness”, as Mr Vane is crushed by the weight of Lilith as she lays on him: 'Came a cold wind with a a burning sting - Lilith was upon me' (Macdonald 85), an image proving the power of Lilith, as she finally manages to have the dominant position on top of a man.

In addition to MacDonald's masterpiece, a number of authors were inspired to infuse the danger of Lilith in the characterisation of their protagonists. Among them, the novella Lilith by Walter Herries Pollock, released in 1874 in the pages of The Temple, and The Soul of Lilith, written in 1895 by Marie Corelli, stood out. In both novels, two women named Lilith (without any direct affiliation to our demoness) lead to the destruction and decay of the male protagonists with their vampires' appeal. These two occurrences show how Lilith was finally incorporated into the mainstream, as the mere mention of her name could sparkle reverential awe and terror in the eyes of the Victorian readership, and project a number of pre-determined features unto new characters.

Lilith as the embodiment of Victorian fears

In a transitional time of dramatic scientific discoveries, philosophical and psychiatric advancements and modernisation, a traditionally Christian Victorian society suffered great inner conflicts that notably emerged through the character of Lilith; indeed, she proved a source of anxiety far beyond her alluring and dominant femininity, shattering the moral expectations of a conservative society.

If the character of Lilith subconsciously ignited passions and anguish from the Victorian audience, it is arguably largely due to her foreign nature, which has been very little studied and identified in a Victorian context. Lilith, or לילית in Hebrew, remains an exotic Talmudic character who -not unlike Dracula- made her way to Great-Britain to allure British men and compromise the ideal of 'Britishness'. Indeed, Judaism became a significant spiritual and foreign entity in Victorian Britain, as 'the number of Jews in Britain rose from 60,000 in 1880 to 300,000 by 1914, as a result of migrants escaping persecution in Russia and eastern Europe' (English Heritage), with an especially important community in East London. From shapeless Jewish demoness, Lilith performed a metamorphosis into the traits of a seducing English Rose, while still remaining the Hebraic Other. She therefore stands as an exceptional occurrence in Victorian Arts, as Jon Thompson identified that 'once individuals are designated as cultural “others” by virtue of being foreign [...] they are scarcely characterized at all or are only handled in the most stereotypical fashion' (Thompson 69); indeed Lilith escaped from the pigeonhole of traditional Victorian depictions of the “villain Jew”, as she concealed her foreign nature in the body of a British lady. It may be argued that this depiction was an example of whitewashing, nevertheless it undeniably allowed the development of her multi-faceted self though her ability to adapt to different audiences. Her Otherness was made more malleably dangerous by her newly-found Britishness.

As a demoness of transcendence, Lilith proved an uncomfortable character for Victorian Britain, since she transcended her original religious role to become a secular and profane cultural icon. Indeed, as Nina Auerbach explains, 'In Victorian England, an age possessed by faith but deprived of dogma, any incursion of the supernatural into the natural became ambiguously awful because unclassifiable' (75). The major appeal of Lilith and her constant presence in Victorian arts could have stemmed from a crumbling Christianity, and her transition from religious texts to secular pieces from the newly-contested biblical origin of humanity, destabilized by Charles Darwin's 1859 theory of evolution. Indeed, 'the man who is generally credited with causing doubt in the minds of Victorian Christians is Charles Darwin' (Scotland 1), though in fact geologists, linguists, and biblical scholars had done so decades earlier. All these factors raised 'questionings as to whether God had by special acts created the world and the creatures which populated it.' Many in England therefore tried to find answers in alternative beliefs; 'as the old certainties crumbled, new faiths emerged, such as Spiritualism, established in England by the 1850s, and Theosophy, which drew on Buddhism and Hinduism' (English Heritage). Lilith was the active witness of the dissolution of Christian hegemony towards a more secular, non-conformist, and even supernatural iconography.

Lilith therefore stirred up feelings of anxiety in Victorian times as she embodied the destruction of a traditional society's foundations and became the testament of a Victorian society in a state of intellectual and social flux.

Conclusion

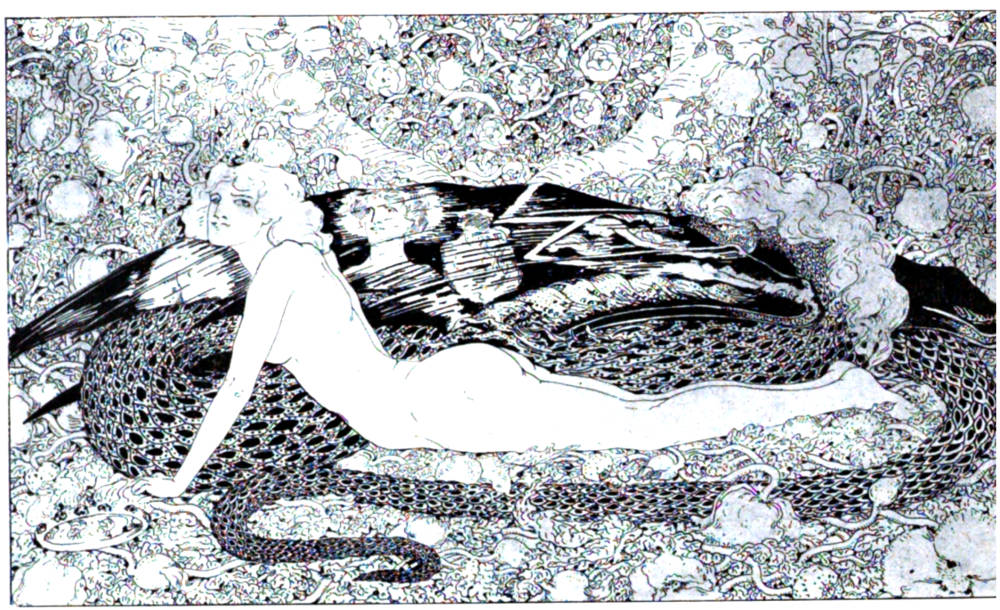

Lilith. Althea Gyles. Illustration from The Dome I (Oct.-Dec. 1898): 235.

The very last occurrence of Lilith in Victorian arts might have been Althea Gyles's illustration from the journal The Dome. Gyles depicts Lilith with her canonical signature look: the nudity, the rose, and the snake. Nevertheless, her long locks were cropped to a short flapper bob; the rebellious element of her hair is still present, but has shifted to an early twentieth-century context, when short bobs proved to be more dissident than long hair. The carefully blended brush strokes of Pre-Raphaelite oil painting techniques were abandoned in favour of modern black and white sharp lines and an Art Nouveau style, continuing to adapt Lilith for a new century with an intact, yet evolving, relevance.

Through her shifting representation in the Victorian pictorial and literary arts, the figure of Lilith proved herself an iconic representation of many Victorian fears. Her sexually dominating allure has been analysed as a castrating and feminist blow during a period that saw the role of women greatly changing, but the examination of British identity she triggered were a cathartic element for Anglo-Saxon audiences. The rise of Lilith's Victorian representations is therefore the story of a demoness' redemption who, through the works of artists who understood the complexity and beauty of her story, morphed her into an icon of progressive transgression in a changing Victorian society.

Bibliography

Allen, Virginia M. "'One Strangling Golden Hair': Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Lady Lilith.” The Art Bulletin. New-York: CAA. 1984

Auerbach, Nina. Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1982

Barringer, Tim, Jason Rosenfeld, and Alison Smith. Pre-Raphaelite: Victorian Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing, 2012

Browning, Robert. “Adam, Lilith and Eve”. The Lilith Project. 1883. Web. Accessed 14 April 2019

Carter, Philip. “The first women at university: remembering ‘the London Nine’”. The World University Rankings. 28 January 2018. Web. Accessed 15 August 2019.

Diniajko, Andrzej. “The New Woman Fiction”. The Victorian Web. 17/12/2011. Web. Accessed 15 April 2019

Gorrell, Robert M. What's in a Word?: Etymological Gossip about Some Interesting English Words. Reno: University of Nevada Press. 2001

Macdonald, George. Lilith. Great Britain: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 1895

McGillis, Roderick F. “George MacDonald and the Lilith Legend in the XIXth Century”. Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature. 6.1 (1979): Article 1.

Patai, Raphael. “Lilith”. The Journal of American Folklore 77, No. 306. Cambridge: American Folklore Society. 1964

“Religion”. English Heritage. Web. Accessed 16 April 2019

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Body's Beauty”. 1881. Poem Hunter. Web. Accessed 17 April 2019

Scotland, Nigel. “Darwin and Doubt and the Response of the Victorian Churches”. Churchman. 100.4. (1986).

Thompson, Jon. Fiction, Crime, and Empire. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. 1993

Yeats, W. B. “A Symbolic Artist and the Coming of Symbolic Art.” The Dome 1 (1998): 233-37. Hathi Trust Digital Library. Web. 30 October 2019.

Last modified 30 October 2019