The illustrations all come from our own website. Click on them for large images, and for more information about them. — Jacqueline Banerjee

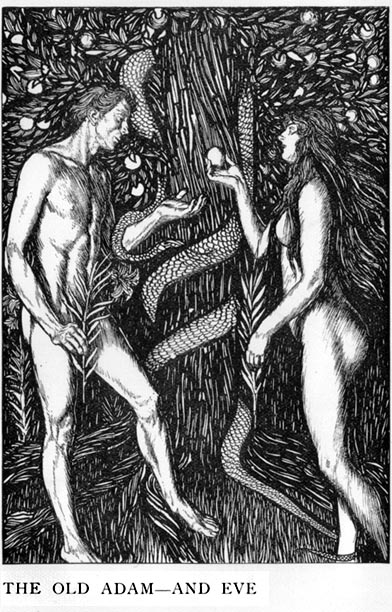

The term "fallen woman" refers to an irrevocable loss of innocence, a concept originating in the biblical fall in the Garden of Eden; the characterisation of Eve as temptress inextricably links her fallen state with the loss of sexual purity. During the Victorian period a woman's identity was indisputably intertwined with her sexual status; a woman was either an untainted "maiden," a wife or mother (which placed her sexuality safely in the domestic sphere), or she was vilified by labels such as "spinster" or "whore," both of which had negative connotations, the former with sexual atrophy, the latter with deviant promiscuity. Essentially, any deviance from the paragon of ideal Victorian womanhood, the "angel of the house," insinuated that a woman's fall was imminent. Each of the novels discussed here portrays a different interpretation of the "fallen woman."

Hetty Sorrel in George Eliot's Adam Bede (1859) is the quintessentially Victorian "fallen woman," that is, a lower-class maiden who is seduced by the idea of a life of "lace satin and jewels," and is sexually corrupted by a man above her station who has no desire to marry her. Similarly, Aunt Esther encapsulates the idea of a fallen woman's fate: we learn that she dies in desolation, "nought but skin and bone," desperate for a "spot to die in peace" (377). While Hetty and Esther provide the tragic beginning and end of the "fallen woman," Lydia Gwilt in Wilkie Collins's Armadale (1866) functions as a far more portentous figure. Characterised as a devious, flame-haired and mercenary, she is described as having the "sexual sorcery" of a "siren" (383). Like a black widow spider she devours the men in her path, from triggering the death of her music teacher at the tender age of thirteen, to poisoning her first husband and sadistically marking Allan Armadale as her next victim. In contrast to Hetty and Esther, Lydia's fallen state does not render her a victim, but an aggressor. Hetty and Esther are victims of society's corrosive condemnation; in contrast, Lydia personifies the patriarchal fear of what might result from an unchecked female sexuality that is irrepressible and impervious to societal judgment.

George Eliot's Adam Bede

Edward H. Corbould's Dinah Morris Preaching on Hayslope Green.

In Adam Bede Hetty Sorrel is implicitly linked with the fallen Eve when she is seen gathering apples, conventionally regarded as the forbidden fruit. Hetty evokes the erotic desires of the flesh, functioning as a foil to Dinah who represents an almost prelapsarian spiritual purity. "What a strange contrast the two figures made ... Hetty, her cheeks flushed, her neck and arms bare, her hair hanging in a curly tangle down her back ... Dinah covered with her long white dress, her pale face full of subdued emotion" (136). Juxtaposed with Dinah's altruistic nature, Hetty's is innately selfish: she consciously wields her beauty to obtain male attention. She even desires to keep Adam under her spell when she has no wish to marry him: "she liked to feel that Adam was in her power, and would have been indignant if he had shown the least sign of slipping from under the yoke of her coquettish tyranny" (84). Therefore, although Hetty's vulnerability is detailed — she is described as having a "childish soul" (111) and all the resilience of a "soft coated pet animal" (326) — her awareness of her own sexuality renders her amenable to her fallen state. In the mythos of the novel Hetty commits an untenable wrong by actively attempting to transcend her class; Hetty's desire to become a "grand lady ... with feathers in her hair" (129) is as condemnable as her sexual transgression. However, society's ultimate persecution comes from her act of infanticide: her actions are no longer just immoral but criminal. In a society that valorized motherhood and conceived of a mother as the bearer of an "elevated position of moral authority" (Zedner 14), Hetty's act of child murder is perceived as irredeemably abhorrent. Any sympathy evoked by Hetty's tragic circumstance is preemptively diluted by her previous remarks at the novel's outset. She shows little regard for Mrs. Poyser's daughter Totty, complaining that children are "worse than nasty little lambs ... for the lambs [are] gotten rid of sooner or later" (132). Hetty is once more the antithesis of Dinah whom Totty goes to happily after she has refused Hetty by "knitting her brow, setting her tiny teeth and leaning forward to slap Hetty on the arm" (126).

Wilkie Collins's Armadale

George Housman Thomas's The Ravishing Miss Gwilt (centre).

However, whilst Hetty covets the life of a lady she is not directly manipulative. In contrast, Lydia Gwilt is the apotheosis of the femme fatale archetype; Lydia harnesses her allure to manipulate men to her will: Allan Armadale, Ozias Midwinter and Mr Bashwood all fall victim to her magnetism. Lydia's fallen state holds more of a Luciferian quality than Hetty's: she is described as a "tigeress" with "devilish beauty" and "devilish cleverness" (364). Richard Altick draws parallels between her red hair and the red hair of devils and demons in medieval drama. Unlike the traditional tragic fallen woman, Lydia is comfortable in her fallen state; she becomes erotically charged at the idea of deception: the feeling of "terrible excitement" at the thought of brushing Armadale's "life out of [her] way" made her "blood leap, and [her] cheek flush" (486). This dark eroticisation of the criminal fallen woman is a convention of the Victorian period and can be seen in Dickens's account of the hanging of Maria Manning: there, he describes the "woman's fine shape; so elaborately corseted and artfully dressed, that it was quite unchanged in its trim appearance as it slowly swung from side to side" (Dickens 162). According to Lombroso, a Victorian criminologist influenced by Social Darwinism, the female criminal is more "depraved" and "terrible" than the male criminal "for criminals are an exception among civilised people and women are an exception among criminals" (41). Lydia Gwilt fits this specification; she appears to be innately fallen and exacerbates the Victorian anxiety that "beneath the façade of the loving honest woman there lurked a darker self" (Zedner 41). Lydia is a natural charlatan effortlessly masquerading when necessary and using "the machinery of the modern metropolis with the expertise of a Victorian James Bond" (Sutherland ix). Even her name hints at her innate criminality "her name chiming 'guilt'" (Altick 323). Lydia's transgressive sexuality aids her criminal activity, but it is also symptomatic of psychological degeneracy. According to the Victorians "uncontrolled sexuality seemed the major almost defining symptom of insanity in women" (Showalter 74). Lydia's psychological instability manifests itself both in her self-destructive nature (indicated by her laudanum addiction and her suicide) and in her sadistic behavior ("do you ever like to see the summer insects kill themselves in the candle?" (166)). Therefore, although Lydia seems at home in her fallen state it is also the source of her self-destruction. Once she admits that her love for Midwinter has "altered" her it is as though the stain of the fallen woman becomes visible to her "is there an unutterable Something left by the horror of my past life ... are there plague spots of past wickedness on my heart?" (546).

Elizabeth Gaskell's Mary Barton

Charles M. Relyea's Mary Barton.

The association between "fallen women" and disease and pollution was not just a metaphorical one. The Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 decreed that women suspected of prostitution were subject to forcible examinations and often placed in hospitals for up to a year. This idea of the fallen woman as a contagion is particularly pertinent to Elizabeth Gaskell's novel Mary Barton (1848). In the Victorian period the threat of lower class female sexuality was seen as "the driving force behind all crime, poverty and social disorder" (Mayhew 35).

The impoverished fallen woman is embodied here in Aunt Esther who conceives of her fallen state as a contagious disease. Just as Lydia almost cries out to Midwinter "Lies! All lies! I"m a fiend in human shape!" (490), Esther warns Mary not to touch her; "not me you must never kiss me" (235). Esther functions as a cautionary omen of what will befall Mary if she succumbs to the upper-class Carson. The narrator emphasises the "unacknowledged influence" (25) Esther has over Mary: Mary decides that "her beauty should make her a lady ... the rank to which she firmly believed her lost aunt Esther had arrived" (26). However, unlike Hetty who dreams of lace and luxury, Mary dreams of ample food for her family and even finding Jem a job once she is Mrs Carson. Mary's refusal of the upper-class Carson and her abrupt acceptance of the working-class Jem removes her from the risk of becoming a "fallen woman."

In conclusion, the fear of the "fallen woman" and the valorisation of the pure "angel of the house" are both indicative of the Victorian need to confine female sexuality to marriage. Even Dinah, a paradigm of saintly virtue, must give up her role as minster in order to become the quintessential "angel of the house." In contrast to Dinah, Hetty is removed from society yet Arthur is incorporated back into life at Hayslope. All three of the "fallen women" of these novels commit offences against the ideal of the "angel of the house"; Hetty and Esther violate the sanctity of marriage by falling pregnant outside of wedlock, and Lydia conceives of marriage not as a sacred union in which to have children but as an opportunity for monetary gain. As soon as these women resist the rules of society they are condemned and fall victim either to death or societal expulsion. In the Victorian period Darwinian theory was appropriated and branded with Victorian moral conventions, asserting that men are born "animals" and women "angels." Whilst it was considered natural for men to indulge in their sexual appetites it was considered perverse and "unnatural" for women to act the same way (see Scott 353-5). Therefore, by using the "fallen woman" archetype each of these novels reveals Victorian culture's belief that female sexuality was dangerous, both to women themselves and to society at large.

William Holman Hunt's Awakening Conscience.

Related Material

- Private vs. Public: Female Sexuality in Victorian Culture

- "What Makes a Fallen Woman Fallen?" (with reference to Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market

- Mary Barton

- Thomas Hardy's "The Ruined Maid"

- The Contagious Diseases Acts

- Fallen Women in Victorian Art

- Augustus Egg, Past and Present

- W. H. Hunt's Awakening Conscience

Works Cited

Altick, Richard. The Presence of the Present: Topics of the Day in the Victorian Novel. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1991.

Collins, Wilkie. Armadale. London: Penguin Classics, 2004.

Dickens, Charles. "Lying Awake." In Selected Short Fiction. London: Penguin, 2005.

Eliot, George. Adam Bede. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Classics, 2003.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. Mary Barton. Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 2006.

Lombroso, Cesare. The Female Offender. New York: Littleton, Co: Fred B. Rothman & Co., 1999.

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor. New York: Dover, 1968.

Scott, Clement. "An Equal Standard of Morality." Humanitarian. 5 (1894): 334-35.

Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture. New York: Pantheon Books, 1985.

Sutherland, John. "Introduction." In Armadale. London: Penguin Classics, 2004.

Zedner, Lucia Women, Crime and Custody in Victorian England. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1991.

Created 22 June 2016