Jim Spates has kindly shared with readers of this site material from his wonderful blog, Why Ruskin. This excerpt from his post of May 2025 has been adapted for our own website, but readers are urged to read the full entry, which addresses a broader range of readers, here. — Jacqueline Banerjee

“All Creatures Great and Small…” (Psalm 104:24)

“He hath made everything beautiful in its time” Ecclesiastes 3:1

If one reads any of Ruskin’s books, beginning with the first volume of Modern Painters, published in 1843, all the way to his last, his marvelous autobiography, Praeterita, published in the 1880s, one finds at the heart of what he is trying to say this recognition of and abiding praise for Creation. Always committed to telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, as far as he was able to discern it, he wrote about those things which are pleasant to most of us (love, babies, dogs, cats, mountain views, flowers), as well as those which are, usually, not so well-regarded. In our busyness, our ignorance, and, often, our foolishness, thoughtless dismissal or disdain, we often miss some of these phenomena, and so, he wrote in such a way that would we would be alerted, or re-alerted, to these, exhorting us to take the time to see and study them and recognize that all were, in their time, beautiful, and essential to the well-being and continuance of Creation.

In 1869, he published a small volume, which continued this theme: The Queen of the Air. On its face, it is his attempt to alert us to the existence and pervasiveness of deep forces at work in the universe which, whether we know of them or not, shape all life. As he developed his thesis, he included a passage that surely some of his readers would have found disconcerting, a passage reflecting on snakes and their role on this earth. He was fully aware that, in history, save for a few cultures, snakes had never been high on a list of the earth’s most beautiful creatures. That passage follows below, and I trust you will give Ruskin's words the cognitive attention they deserve:

he dead hieroglyph may have meant this or that — the living hieroglyph means always the same; but remember, it is just as much a hieroglyph as the other. Nay, more, — a "sacred or reserved sculpture," – a thing with an inner language. The serpent crest of the king’s crown, or of the god's, on the pillars of Egypt, is a mystery, but the serpent itself gliding past the pillar’s foot, is it less of a mystery? Is there, indeed, no tongue except the mute forked flash from its lips, in that running brook of horror on the ground?

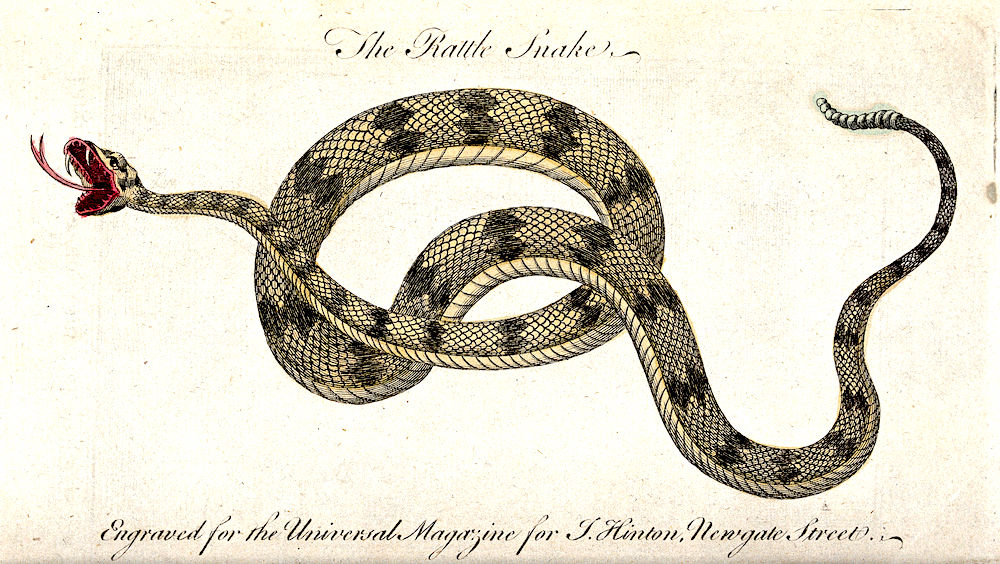

Coloured etching of a rattle snake. Wellcome Collection (Reference 41204i): public domain. Ruskin's own paintings of snakes can be found in the collection of the Ruskin Drawing School: see Robert Hewison on The Queen of the Air, n. 7.

Why that horror? We all feel it. Yet how imaginative it is, how disproportionate to the real strength of the creature! There is more poison in an ill-kept drain, — in a pool of dish-washings [soap] at a cottage door than in the deadliest asp of the Nile. Every back-yard which you look down into from [your seat on] the railway as it carries you out by Vauxhall or Deptford, holds its coiled serpent: all the walls of those ghastly suburbs are enclosures of tank temples for serpent-worship; yet you feel no horror in looking down into them, as you would if you saw the livid scales, and lifted head. There is more venom, mortal, inevitable, in a single word, sometimes, or in the gliding entrance of a wordless thought.... But that horror [we feel] is of the myth, not of the creature. There are myriads lower than this, and more loathsome in the scale of being; the links between dead matter and animation drift everywhere unseen. But it is the strength of the base element that is so dreadful in the serpent; it is the very omnipotence of the earth. That rivulet of small silver — how does it flow, think you? It literally rows on the earth, with every scale for an oar; it bites the dust with the ridges of its body. Watch it, when it moves slowly:— A wave, but without wind! a current, but with no fall! all the body moving at the same instant, yet some of it to one side, some to another, or some forward, and the rest of the coil backwards, but all with the same calm will and equal way — no contraction, no extension; one soundless, causeless, march of sequent rings, and spectral processions of spotted dust, with dissolution in its fangs, dislocation in its coils. Startle it;— the winding stream will become a twisted arrow;— the wave of poisoned life will lash through the grass like a cast lance… it is passive to the sun and shade, and is cold or hot like a stone; yet “it can outclimb the monkey, outswim the fish, outleap the zebra, outwrestle the athlete, and outcrush the tiger!” It is a divine hieroglyph of the demoniac power of the earth, — of the entire earthly nature. As the bird is the clothed power of the air, so this is the clothed power of the dust; as the bird the symbol of the spirit of life, so this of the grasp and sting of death. [81-84]

In this way, Ruskin asks us to pay heed to, not to mention honor and revere, all the creatures we encounter, whether great and small, instantly appealing — or daunting.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Ruskin, John. The Queen of the Air: Being a Study of the Greek Myths of Cloud and Storm. London: Smith, Elder, 1869. Internet Archive. Web. 22 June 2025.

Created 22 June 2025