[The author has kindly shared with readers of the Victorian Web this review essay from his Open Letters Monthly: An Arts and Literature Review. Thanks to Nigel Banerjee for suggesting it and to Jacqueline Banerjee for gaining permission from Mr. Donoghue. George P. Landow formatted it for this site. All illustrations except for the last come from Open Letters Monthly.]

Recently a visiting young friend was surveying a bow window stack of books in my apartment and, laughing out loud at one particular volume, declaimed:

Who shall tempt with wandering feet

The dark, unbottomed, infinite abyss,

and through the palpable obscure find out

His uncouth way?

(My friend has been on a bit of a Milton bender lately). The uncouth way here, the dark, unbottomed, infinite abyss was John Ruskin: The Early Years by Tim Hilton (1985), and my friend’s implication — in fact, his outright pronouncement, was that such a book could only appeal to the lover of obiter dicta, the reader of Statius for pleasure (in Latin, of course), the snapper up of odd intellectual trifles. Such is the state of affairs with Ruskin and today’s young Turks. But it was not always so.

One hundred and fifty years ago, he ruled the Western intellectual world with a breadth and thoroughness that hadn’t been seen in centuries. Socialist workman’s groups, lace-curtained Mayfair reading rooms, rough and tumble Colorado mining towns, and not only the lecture halls of Boston and Oxford but their boarding houses as well — all these were conquered by Ruskin in the 1840s and 1850s. Conquered many times over, for Ruskin’s writings extended to many different fields of interest, but conquered mainly by the same instrument: Ruskin’s magnificent prose, at once hortatively beautiful and grippingly personal (as when writing about the humble barn swallow: “It is an owl that has been trained by the Graces. It is a bat that loves the morning light. It is the aerial reflection of a dolphin. It is the tender domestication of a trout”).

He was born in London in 1819, the only child of prosperous, business-class parents who educated him at home and sent him to Oxford as a “gentleman commoner” student (that is, likely to attend lectures, but unlikely to take a degree)(when an early volume of his poetry won a prestigious prize, he was awarded a degree in any case). He published the first volume of his Modern Painters in 1843 when he was only 24 years old, and it stormed the redoubts of Victorian traditionalism — in it, Ruskin championed contemporary art, especially that then being produced by J. M. W. Turner, as fully the equal of the most venerated masters of the Renaissance, and he performed this feat of irreverence with such knowledge and rhetorical skill that the book couldn’t be ignored, indeed couldn’t avoid being lionized and demonized in every bookstore and circulating library from Calais to California (pirated American editions of Ruskin sold as fast as they could be printed). It made Ruskin a name, and greater fame was to come. In 1849 he published the first volume of The Seven Lamps of Architecture (complete text), his ode to the ongoing revival in Gothic style, and it, too, became a sensation, extolling the quintessential Victorian credo that in order for anything to be truly great, it must first be good, worthy. The book was another step along the path to the love affair that would define Ruskin’s life — not a love affair with a human being (his were uniformly disastrous, as we’ll see), but with a city.

The city was Venice, and the love affair is the subject of Robert Hewison’s stupendous, final-word volume Ruskin on Venice. Hewison enthusiastically acknowledges his debt to Ruskin biographer Tim Hilton (pace our Milton-quoter), but his sumptuously illustrated book is really a grand reiteration of Hewison’s own 1978 volume Ruskin and Venice. The change from “and” to “on” signals the marvelous change from the first volume to the second: where once we got mostly narrative, now we get narrative plus generous amounts of stimulating digressions.

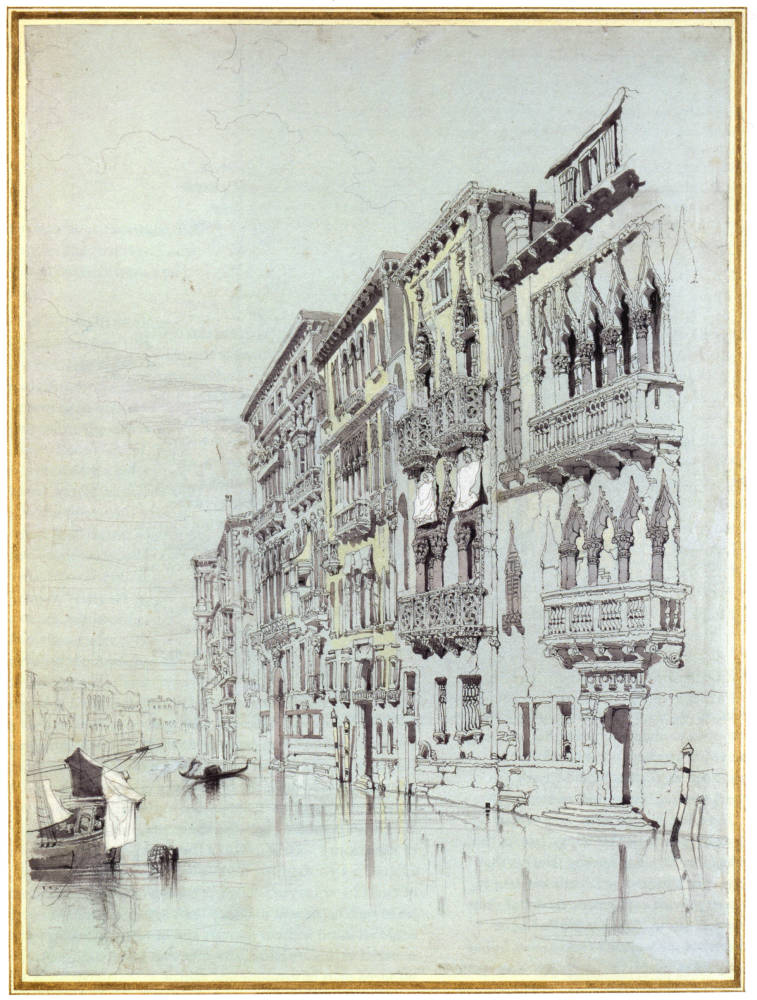

Casa Manin and Casa Grimani, John Ruskin 1870

Hewison here proves himself equally skillful at both following the complicated nature of Ruskin’s day-to-day life and exploring the equally complicated and wide-ranging web of his writings. His account might fall short of the pure sympathetic beauty of Hilton’s prose (he’d probably agree that everybody’s does — in Hilton, Ruskin has found the biographer all tortured souls dream about [for different view]), but he makes that very deficit a strength, showing us how strange Ruskin could be and seem, even to his own contemporaries and friends. Yale University Press has done a stunning job in the physical presentation of this book (it abounds with color plates, black-and-white inserts, and some rare daguerreotypes), but it’s Hewison’s lively, scrupulous text that forms the main attraction. This is not a mindless coffee table book — it’s a synthesis of a lifetime of lively scholarship, and on the subject of Ruskin and the city that so powerfully ensnared his imagination, it’s unlikely to be surpassed.

South side of St. Marks seen from the loggia of the Ducal Palace, Venice. John Ruskin. 1850.

Ruskin first saw the Princess of the Adriatic in 1835 when he was sixteen and on a kind of Grand Tour with his generous, supportive, intrusive, manipulative parents (Hewison calls their relationship “crushingly claustrophobic”). He was instantly enraptured. The Princess had had countless suitors before him, of course: Marco Polo had called it a playground; Vivaldi had called it a songbird; Erasmus had myopically commented on the unending pageantry of the Grand Canal.

But no lover could compare to the one who came to her almost as soon as Napoleon’s defeat made international travel safe again: in 1816, Lord Byron took up residence in the Palazzo Mocenigo on the Grand Canal, and by 1835 his verses and plays on this most famously decadent city had become a part of the air Ruskin breathed. Childe Harold had prepared young Ruskin for the floating city long before he ever actually set eyes on her — as Hewison aptly points out, Venice “has always been an imagined city,” and he expertly sets the stage for what Ruskin would encounter:

Five changes of government, four military campaigns, a wrecked economy, the withdrawal of Venice’s patrician leaders from public life, and seven years of poor weather and bad harvests between 1796 and 1814 meant that the city was shabby and decayed when Byron arrived in 1816.

In 1797 Napoleon had famously extinguished the thousand-year-old Venetian Republic, and in 1815 the Austrians took the city, trying in their ham-handed way to make everything more efficient — and failing miserably, since Venice resists all non-Venetian ideas of efficiency as complacently as housecats resist the call to exercise. But the one thing the Austrians could at least begin was the slow and ungainly movement of Venice into the modern era, thus opening up the two-century struggle that still defines the city — and that certainly defined Ruskin’s love-hate relationship with her overseers. Primed by the Romantics and the lachrymose sentimental streak that ran through the Victorian era, Ruskin opened that relationship in breathless love, as he relates in one volume of his Præterita:

that the fairy tale should come true now seemed wholly incredible, and the start from the gate of Padua in the morning, — Venice, asserted by people whom we could not but believe, to be really over there, on the horizon, in the sea! How to tell the feeling of it!

But as another famous lover of Venice once put it, “After paradise — that’s when love stories get interesting.”

It was in the full swoon of that first love that Ruskin wrote the first volume of the book that would change his life — and Venice’s life — forever: in 1853 he published The Stones of Venice, in which he venerated the Gothic architectural marvels of that city over all other styles and proclaimed the Doge’s Palace the wonder and marvel of the world. The book was draped in the most arresting prose Ruskin knew how to write, and it gradually ascends throughout its length from investigation to outright love poem, culminating in the famous final paragraph:

A city of marble, did I say? Nay, rather a golden city, paved with emerald. For truly, every pinnacle and turret glanced or glowed, overlaid with gold, or bossed with jasper. Beneath, the unsullied sea drew in deep breathing to and fro, its eddies of green wave. Deep-hearted, majestic, terrible as the sea, — the men of Venice moved in sway of power and war; pure as her pillars of alabaster, stood her mothers and maidens; from foot to brow, all noble, walked her knights; the low bronzed gleaming of sea-rusted armour shot angrily under their blood-red mantle-folds. Fearless, faithful, patient, impenetrable, implacable, — every word a fate — sat her senate. In hope and honour, lulled by flowing of wave around their isles of sacred sand, each with his name written and the cross graved at his side, lay her dead. A wonderful piece of the world. Rather, itself a world.

The effect was more powerful and wide-reaching than Ruskin could possibly have dreamt. By maintaining that Venice’s internal corruption (social, commercial, the mean ol’ Catholic Church, etc) had caused her to lapse into the state of semi-ruin in which she now stood, Ruskin was looking longingly at the past — but most of his readers saw it as a summons to the future. A wave of neo-Gothic building (which Ruskin promptly despised) swept the West, and restoration committees sprang up on every street corner in Venice, intent on saving the city’s crumbling architectural wonders.

Urban restoration is always a nightmare, underfunded, usually underthought, almost always regretted in hindsight — “a very modern controversy,” Hewison calls the nineteenth-century restoration of St. Mark’s that went on in Ruskin’s lifetime, although he could just as easily be talking about the tearing down of Penn Station, or the razing of Scollay Square in the 20th. Visitors to Venice today would scarcely believe the state into which the city had fallen after Napoleon and the Austrians got done with her. And viewing the surviving photographs with horror, they would scarcely believe anybody could have argued against restoration (Hewison helpfully includes a great many of these shudder-inducing photos in his book). And surely if anybody did argue against, it would be some unbalanced lunatic, not the city’s foremost lover-in-prose? And yet there was Ruskin himself, railing away:

Do not let us talk of restoration. The thing is a Lie from beginning to end. You may make a model of a building as you may of a corpse, and the model may have the shell of the old walls within it as your cast might have the skeleton, with what advantage I neither see nor care: but the building is destroyed, and that more totally and mercilessly than if it had sunk into a heap of dust, or melted into a mass of clay.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of Hewison’s book is that he’s seldom content to let Ruskin have the last word, especially when Ruskin is mostly in the wrong. Here he rejoins:

Yet as modern Venetian urban historian Giandomenico Romanelli has pointed out, in the 1860s and 1870s for the Venetians �restoration’ was precisely that, a recovery of the city’s architectural glories, as opposed to the retention of reminders of her melancholy and defeated past. It was bringing a corpse back to life.

About Ruskin’s more florid sentiments, Hewison wryly comments, “This is not the sort of commentary one might expect to find in a history of architecture.” No indeed, and you’ll find no trace of it in, for instance, William Dean Howells’ chatty and jaunty 1866 account of his own life in Venice. Part of this was the Howells knew that jaunty usually sells better than jaundiced, but part of it was also that by midcentury, Ruskin was an unbalanced lunatic — and it was love that was to blame.

As close to love as Ruskin could come, that is. He first met Rose LeTouche when he was 38 and she was 10, and he fell in love with her “purity” and immediately began thinking of marriage. His busy schedule and her worried parents conspired to keep them mostly apart for the next few years, but she turned 18 at the beginning of 1866, and he proposed. She told him to wait three years for an answer, but they didn’t even see each other again for four years, during which time Ruskin’s obsession only grew stronger (perhaps not coincidentally, he also began experiencing mental breakdowns that would grow worse with time). The analogy with Dante and the child Beatrice was no doubt irresistible to Ruskin, and like Dante, there may have been some unconscious calculation involved, as Hewison shrewdly points out:

[Rose was] the worst possible choice of someone to fall in love with, but it may be that that was the point. She was a fantasy, and though his feelings for her after her eighteenth birthday became increasingly sexual, to obtain her would have spoiled the dream.

The potential marriage was forestalled in part because Ruskin’s actual marriage, to Effie Millais, had ended badly — and famously. After she accused him of impotence and “sexual abnormality,” he responded that although he found her attractive, something about her was grotesque (the decorum of the time relieved him of needing to get specific, and Ruskin scholars have debated what the offending detail could have been. Body odor? Pubic hair? An actual vagina? The evenings get long, for Ruskin scholars). They were granted an annulment, but the conditions were such that if Ruskin were to marry again and father children, the annulment would be invalid and the second marriage would be bigamous.

In the meantime, the strain on all those around him — especially his family friends the Severns and the Hillards — was considerable, as he pressed for more contact with Rose and she (under strain of her own from worsening tuberculosis) contrived to both encourage and dissuade him. Tensions could often be acute, and in one remarkable instance — when the whole group was visiting Ruskin in Venice in 1872 — those tensions are actually photographed. Hewison has his sly brand of fun analyzing:

This situation accounts for the drama beneath the surface of one of the most unusual souvenir photographs ever taken. � superficially this group portrait . . . records the Ruskin party on holiday in Venice. But a boiling row is taking place. On the right sits and embarrassed Albert Goodwin, who also happens to be unwell. At his feet sits an equally embarrassed Constance Hilliard, while above her stands a furious Arthur Severn, his right arm on the chair of a tight-lipped Joan. Mrs. Hilliard stands, keeping her distance, while on the left Ruskin sadly sits, his eyes on the middle distance and his mouth set.

In the end it didn’t matter: Rose’s condition worsened, and her parents permitted Ruskin to visit her bedside several times while she was in London in early 1875 (he drew a pencil sketch of her, looking gaunt, pointed, and impossibly unhappy). Rose died of tuberculosis in late May at her family’s home in Ireland while Ruskin was in England. He was informed by telegram, and as soon as he could make the arrangements, he repaired to Venice to heal his broken heart. There he was plunged into his usual activities in the city — meeting and encouraging (and often underwriting) artists, touring sites, and most of all drawing. Ruskin On Venice does a gorgeous job reproducing a vast number of Ruskin’s watercolors and pencil sketches from the lifetime of visits he paid to Venice — the summary effect is almost sufficient to call for a reassessment of status as an artist, quite apart from his ever having written a word. My most pleasant discovery this time around was the sharp, nervous talent behind Ruskin’s black-and-white sketches: they show the clarity of Ruskin the photography enthusiast (and pioneer) rather than the gauziness of Ruskin the Turner devotee (and manqué).

Left: The Ca d'Oro in 1845. Right: Casa Contarini Fasan, Venice by John Ruskin. 1841.

Ruskin’s last decade was spent almost entirely in the silence of near-total dementia, but in the letters and journal entries of earlier decades, we find him again and again returning not only to The Stones of Venice (although he wrote many other books, the conclusion is inescapable that he knew he’d written only one truly great one) but to Venice itself, the city that so many readers of his age had come to associate with him. He felt the association himself, the sense that he could write about this place as he could about no other, in prose such as she had never received before. He himself usually expressed a polite estimation of that prose, at one point writing, “I know exactly what I had got to say, put the words firmly in their places like so many stitches, hemmed the edges of chapters round with what seemed to me graceful flourishes, touched them finally with my cunningest points of colour, and read the work to papa and mamma at breakfast next morning, as a girl shows her sampler.”

But even his offhand references to Venice are filled with light, as in a 1869 letter (ironically, to his mother):

Here in one city maybe seen the effects of extreme aristocracy and extreme democracy — of the highest virtues and the worst sins — of the greatest arts and the most rude simplicities of humanity. It is the history of all men, not �in a nutshell’, but in a nautilus shell — my white nautilus that I painted so carefully is a lovely type of Venice.

Robert Hewison writes that through Ruskin’s works, Venice is “constantly resurrected,” but he’s leaving out his own substantial contribution. As inconceivable as the thought would have been to the Victorians, nobody today reads Ruskin — he’s preserved, in books like this one, very much as he sought to preserve Venice: expertly, in large fragments, and with infectious enthusiasm.

Last modified 30 April 2024