This review first appeared in the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where the original can be seen here. The author has reformatted and illustrated it for the Victorian Web, adding links and captions, with the kind permission of the journal. Please click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.

This is a book that was waiting to be written. The fundamental point of Victorian Visions of Suburban Utopia may seem obvious, but never before has it been worked out so thoroughly, on this scale or in such depth, across disciplines and in both Britain and America (and even further afield). Better still, it is written with enthusiasm and clarity, and generously illustrated. Nathaniel Robert Walker argues, and fully demonstrates, that Ebenezer Howard of Garden Suburb fame, and Frank Lloyd Wright, with his ideal of a decentralised, America-wide “Broadacre City,” were among the many planners and architects of their age to have been inspired by literary works — specifically, the soft science fiction Utopias then being published on both sides of the Atlantic. What better proof of the influence of creative writing, and the interaction of the arts and sciences?

Robert Owen.

Walker gives Robert Owen a prominent place here, recalling Owen’s hatred of cities and pointing out that, while he found inspiration in the classical past, he insisted that he would base his alternative plans on new scientific principles. This turned out to be a potent combination: “In the decades following Owen’s death, scores of Utopian visionaries in England and America replicated his powerful combination of backward-looking historical reference and forward-looking scientific optimism” (15). Their common goal was to posit an alternative to a life of urban squalor, with its detrimental effects on human comfort, health, relationships and morality.

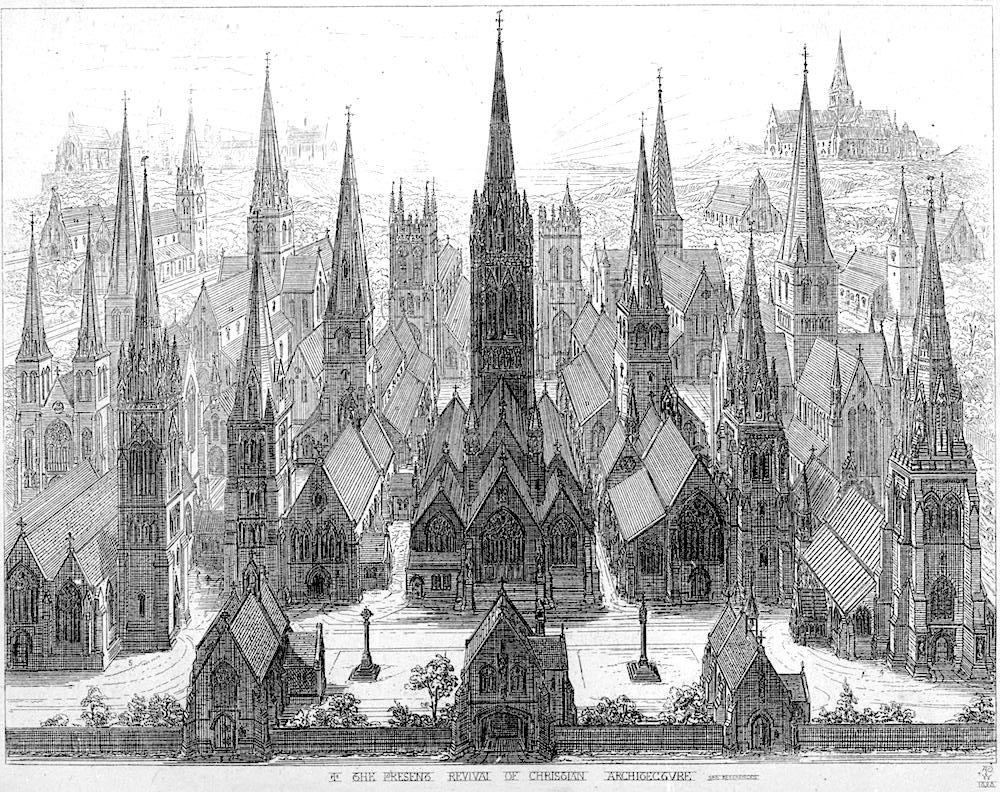

But the ideological background of the Victorians’ utopian dreams goes back much further than Owen. Sir Thomas More and Francis Bacon both get an airing in Walker’s first chapter. In those days, London had yet to become the “great Wen” that riled William Cobbett. Not surprisingly, then, More’s imaginary Utopia has fifty-four cities and is “definitely urban” (41). Bacon, for his part, is rather vague about the built environment in New Atlantis. But what the two agree on, Walker notes, is the beneficial influence of gardening — a definite hint for the future, and one of which Cobbett (whose market garden in Kensington is now partially occupied by Kensington High Street tube station) would have thoroughly approved. Because of its exponential growth in the Victorian period, and the resultant large pockets of squalor, London attracts particular attention in this and the following chapter. It fostered a new wave of utopian writing, as well as scientific and technological advance and painfully gradual reforms. Moving forward in time, therefore, this second chapter is entitled “Socialist Schemes and Suburban Dreams,” and focuses on the visionaries of the earlier part of the Victorian period, with the architect A. W. N. Pugin making a welcome appearance in this wider context, appealing in his Contrasts of 1836 for a return to godliness in a society now, it seemed, fast in retreat from it — a godliness which would be symbolised in the spires of its Gothic Revival churches reaching towards heaven.

Left: Pugin's vision of a country revitalised by a return to piety. Right: A distant view of Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Pugin’s would not be the only plan to combat the “Great Wen” with a more orderly arrangement. William Bonython Moffat, early partner of architect George Gilbert Scott, approached the problem from a philanthropic angle, proposing to settle the working classes in villages around London with “a pure atmosphere and healthy soil” (qtd. in Walker 97), and churches, institutes, public baths and so on. But with the advent of new building materials, the proliferation of inner-city jungles could also be contrasted with a scintillating new vision, first represented in England by the Crystal Place in London’s Hyde Park and its progeny. In Benjamin Lumley’s Another World, or Fragments from the Star City of Montalluyah (1873) about the highly developed civilisation on Mars, the “light” of science is able to “displace darkness” in an Orientalized townscape owing much to another Owen – Owen Jones, who was largely responsible for the interiors of the Crystal Palace (qtd. in Walker 152). Although it was even more of a fantasy than medieval godliness, this exotic and forward-looking vision was alluring. As politicians struggled to provide remedies for urban squalor, protest also found a more direct voice in non-fiction and the work of critics such as (and principally) John Ruskin. Chapter Three shows how different solutions were emerging from this melee, “as authors of the 1870s swung between detached garden cottages, or collective apartment buildings set in parks, with some points in between” (11).

Left to right: (a) Holly Village in Highgate, built by H. A. Darbishire for Baronness Angela Burdett-Coutts, as early as 1865. (b) A row of three houses in Bedford Park, W4, by Richard Norman Shaw and E. J. May (this is often considered to be London's first garden suburb), c. 1880. (c) Houses at the model town of Port Sunlight on the Wirral.

Later chapters deal with the increasing popularity of science fiction, and the trend towards utopian fiction and urban dispersal in America as well, leading up to Edward Bellamy’s best-selling and enormously influential novel, Looking Backward, 2000-1887, first published in America in 1888, but achieving its full potential after being published by Houghton Mifflin in the following year — to be swiftly followed on the other side of the Atlantic by William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890). It is fascinating to see this kind of dovetailing, with, as Walker points out at the end of Chapter Six, New York and London being “now condemned in virtually the same breath” (388). Morris’s vision was very much his own. His pastoral brand of socialism fell short of Bellamy’s proposal to nationalise all private property and even the distribution network; in fact it served as a response to that. Nevertheless, Bellamy himself was drawn to it, as was the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Talking about Morris, Walker makes clear both the line of descent and the broad agreement between these two very influential writers:

Morris knew he could not throw the city away completely, as indicated by the letters to his wife and even by his own thoughts on the “intellectual life” of cities that he had formulated under the “Elm-tree.” The most he could wish for was a world that possessed “all the advantages of city and country, without any of the numerous inconveniences, disadvantages or evils of either.” This was the radical promise Robert Owen had made to the people of Cincinnati in 1829. That vision had been nursed by more than a dozen utopian authors in Britain and America since that time, including the superstar Edward Bellamy, and it was the futuristic dream that Morris offered the world in 1890 (367).

For all its mockery of such a promise, the inevitable dystopian backlash by other writers, like H. G. Wells in When the Sleeper Wakes (first serialised in 1888-89, even before News from Nowhere came out), was again animated by one goal: to provide a human scale, and green spaces, for life in the coming centuries.

Wells's Sleeper wakes to a new world of extraordinary architecture, cantilevers and cables, with people moving around in strange contraptions.

But it was at this juncture that the vision began to warp: enter Robert Blatchford’s enormously popular Merrie England: A Plain Exposition of Socialism (1893), with its “regular expressions of racism and anti-Semitism” (465). As Walker had warned us in his introduction, here was “a demon whose shadow had haunted reform discourse in previous years,” now “armed most fearfully by ongoing developments in eugenic theory” (12). As if some cataclysmic change was now needed, a whole sub-genre of science fiction appeared around this time, in which London was hit by catastrophe — swamped, burned, ruined. “There was no more London,” Grant Allen announced triumphantly at the end of “The Thames Valley Catastrophe,” a short story in the Strand Magazine of 1897 (not mentioned by Walker, who focuses on other examples). The time had clearly come for a fresh start, a new outlook.

Walker’s book ends on a surprisingly optimistic note. He feels that science fiction writers and architects alike, and in concert, rose to the challenge, engaging in the iconoclastic modernism of the early twentieth century. Influence flowed both ways. Wells read Le Corbusier’s Urbanisme (1925) in translation, Walker tells us, while the sets of the film adaptation of Wells’s The Shape of Things to Come (1936) are strikingly similar to the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, of 1935, designed by Eric Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff to much acclaim — a “sleek, glassy celebration of modern materials and construction techniques” (512). Walker concludes, “if the Victorian utopian visionaries taught any lessons of enduring value, one of the most important may be that human dreams really do have the power to change the world” (525).

Yet the pursuit of Robert Owen’s dream of a New Jerusalem, with people living in “green belt” communities, has not been without its cost. It has involved the sacrifice of many fine Victorian buildings, both rural and urban, especially during the 1960s. The green belt itself has been subject to considerable pressure, and erosion. And, minus the political agendas proposed by many of the dreamers, the provision of houses of any kind has become increasingly inadequate. For young people starting out in Britain today, Owen’s dream must still seem a mirage.

Related Material

- Science and Technology in Victorian Utopias

- Homesick in Utopia: State Capitalism and Pathology in Novels of the 1880s and 1890s

- Garden Suburbs: Architecture, Landscape and Modernity 1880-1940

- Bedford Park, London's First Garden Suburb

- [Review by Sarah Bilston of] Laura Whelan's Class, Culture and Suburban Anxieties in the Victorian Era

Bibliography

Walker, Nathaniel Robert. Victorian Visions of Suburban Utopia: Abandoning Babylon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. Hardback, 557 pp. 35 plates and 100 black and white illustrations. ISBN: 978-0198861447. £110.

Created 2 April 2021