William Henry Giles Kingston was bound to get a glowing obituary in the The Boy's Own Paper: he was involved with the periodical from the outset, in 1879, and in the short time left to him was an important contributor. Published by the Religious Tract Society up until 1939, the Boy's Own Paper had a strong Christian purpose and ethos, which is very evident from Kingston's farewell letter, printed near the end of the obituary. Several Reverends were among the contributors to this volume.

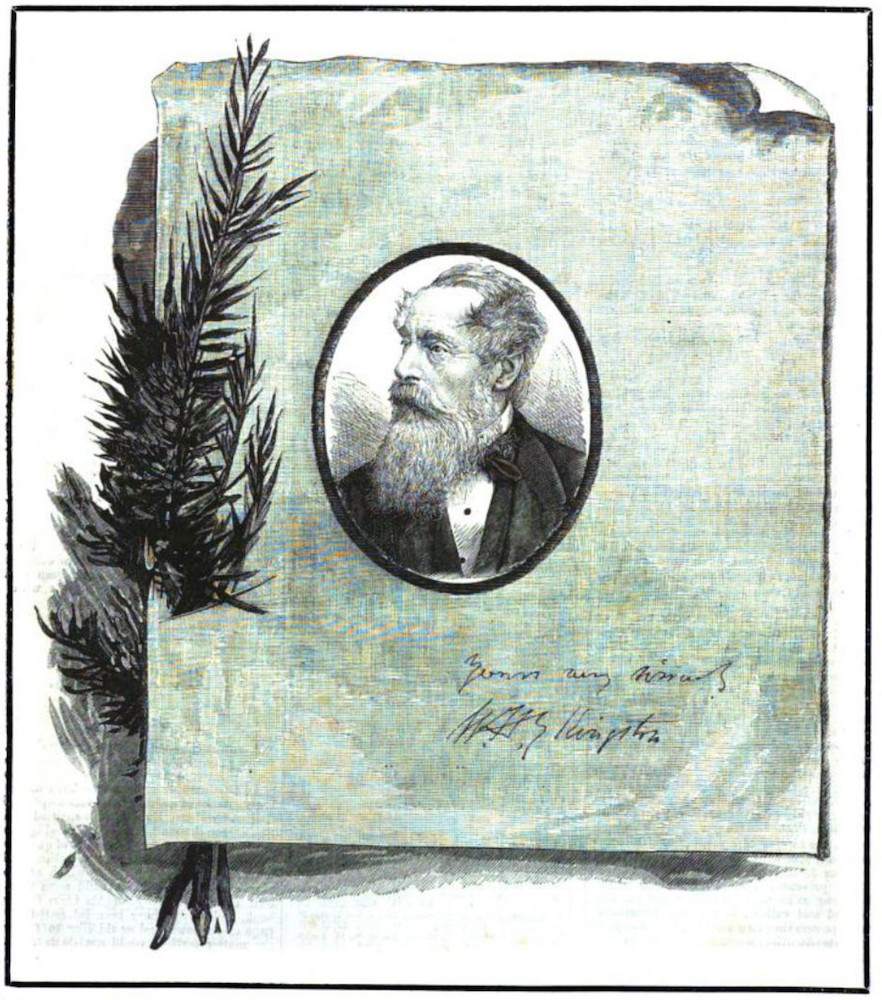

William Heysham Overend, ROI (1851-1898), who supplied the framing device for the memorial photo below right, specialised in marine illustration, and only began contributing to the periodical that year (1880). The recent connection was clearly considered worth communicating. — Jacqueline Banerjee

THE LATE W. H. G. KINGSTON.

W.H.G. Kingston, photograph (late 1870s)

with frame by William Heysham Overend.

Most of our English readers, at least, must have heard by this time of the death, on August 5th, of the veteran writer whose books, for best part of half a century, have charmed and instructed and encouraged for their life-work all classes of boys. That our own readers, numbering in the aggregate, we suppose, little short of half a million, sorrow for the loss is proved by the number of sympathetic letters we have received; and even by the thoughtless yet perhaps very pardonable impatience evinced by many for this memento of their departed friend. When the news of Mr. Kingston’s death reached us, almost immediately after the sad event, the whole of the numbers preceding this were printing; and what may have seemed, therefore, a long delay, is but the inevitable consequence of the large circulation which English-speaking boys the world over have given to their “Own Paper."

Mr. William Henry Giles Kingston was the eldest son of the late L. H. Kingston, and grandson of the late Hon. Mr. Justice Rooke (Sir Giles Rooke), and he was bom in Harley Street on February 28th, 1814. The family resided many years in Oporto, where his father was in business as a merchant, and he had between home and school many voyages to and fro. His education was carefully attended to, with private tutors and at various schools, and in consequence of family connections he had much opportunity of being in the society of seafaring men, in whose company he appeared always to be thoroughly at ease.

From his earliest boyhood he evinced a strong liking for the sea, and desired at one time to enter the Navy. Providence had ordered it otherwise, however, and he remained for some years in charge of his father’s business at Oporto, and after returning to England went into business for a brief period, we believe, on his own account. He was happily able, more than once, to gratify his taste for the sea, and to the end of his life cherished an ardent affection for and deep interest in the Royal Navy — a fact of which his first story in our pages, “From Powder Monkey to Admiral,” with other of his sea tales, affords abundant proof.

His first work, “The Circassian Chief,” was given to the world in 1844, and the success it met with so encouraged him that he shortly afterwards, in 1845, produced “The Prime Minister,” a Portuguese story of the times of the great Marquis of Pombal. This was followed in the same year by “Lusitanian Sketches,” being an account of his own travels and adventures in Portugal, and was in its turn succeeded, in 1856, by “Western Wanderings,” a record of travels in Canada. His first boy’s book, “Peter the Whaler,” was published in 1850, and was quickly followed by a whole series of tales of adventure and travel for boys, a more detailed list of which would more than fill this page. We have before us as we write such a list, and it embraces over one hundred and thirty volumes, including “Captain Cook’s Voyages,” “A Yacht Voyage round England,” and several others, published at the office of this paper. The majority of his books are for boys and sailors, though the girls, and parents, are not entirely overlooked. For sailors he specially wrote "Blue Jackets; or, Chips of the Old Block,” published in 1853 and now out of print; and "Hearty Words to my Sailor Friends,” in 1856.

As already mentioned, Mr. Kingston when a boy had a great wish to enter the Royal Navy, and, as his love for the sea never left him, in later life many opportunities were afforded him by friends to take cruises on board men-of-war, by which means he gained a practical knowledge of seamanship, which enabled him to give his graphic pictures of sailor life. For several years be was constan tly afloat, either in his own yacht, merchant vessels, or men-of-war. After a tour through the southern part of Europe he resided for some time in Portugal, where the civil war was still going on, and afterwards travelled through Holland, Belgium, Germany, and Spain. He next visited Canada and the United States, and turned to capital account, as our readers are aware, the knowledge of men and manners which he gained during his travels.

Early in his literary career he wrote some articles on the state of Portugal, and these, translated into Portuguese, assisted to bring about the commercial treaty then pending between England and that country. As a proof that the service he had rendered was appreciated, Mr. Kingston had the honour of receiving an order of knighthood from the Queen of Portugal, transmitted to him by the Duke de Palmella, through the Viscount de Moncorvo, her Majesty’s ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. Then, on his return to England, he was engaged in promoting an improved system of emigration, and for some time acted as hon. secretary of a colonisation society, formed for that object. He also visited the Western Islands, Shetland, and the Highlands, on a mission from her Majesty’s Emigration Commissioners, and delivered lectures in various parts of the country, his pen being likewise basily employed in the service. He was amongst the first promoters of the Volunteer movement, and the originator of a Society for the Improvement of the Religious and Moral Condition of Seamen, which has exercised a most beneficial effect. His life has thus been essentially a busy and a useful one; and a letter which we shall presently give will serve to show, perhaps better than anything else could, the main motive and sustaining power in all his labours.

Mr. Kingston's interest in and admiration for the BOY'S OWN PAPER was both deep and warm, and he looked upon it as the beau ideal of what a boy’s magazine should be. Shortly before his fatal illness he came to consult with us about his name being used, not only without his authority, but greatly to his annoyance, by one of the ordinary rut of boy’s journals, that had obtained from some publisher to whom he had a long time previously sold one of his books permission to use it. He felt very acutely his thus having his name employed without his having the power to prevent it by a journal “for which nothing could have induced him to write or to otherwise afford his sanction.” We then chatted over the forthcoming new volume of the BOY'S OWN PAPER. On our suggesting the subject for a lengthy serial story, he undertook at once to set about it. About a fortnight later we received from him the mournful intelligence that he was seized by what promised to be a fatal illness, and feared his work was done. He rallied slightly, however, and a few days later he wrote again : “The doctors assure me I may live on for some time, and be able to work with tolerable freedom from pain. As it is most important that I should work as long as I have life, if you have not yet arranged with any one to do the Arctic story I shall be very thankful to try and write it. I will endeavour to make a sketch of the plan, so that another hand maybe able to finish it should mine fail.”

This was written on the 1st of July. On the 8th he wrote: “My strength varies so much that I am very sure it would not do for you to depend on a tale from me to appear as early as the 1st of September. I am very anxious to write it .... but some days I can do little or nothing. Pray understand that I am not writing for any other magazine.” Thus the end was surely creeping on; and the messages received from him from time to time showed that it could hardly be very far off. He evidently felt that the remaining hours were now few, and when face to face with death he sent us to lay before our readers the following letter:—

Stormont Lodge,

Willesden

Aug. 2nd, 1880.

My dear Boys,

I have been engaged, as you know, for a very large portion of my life in writing books for you. This occupation has been a source of the greatest pleasure anel satisfaction to me, and, I am willing to believe, to you also.

Our connection with each other in this world must, however, shortly cease.

I have for some time been sufferlng from serious illness, and have been informed by the highest medical authorities that my days are numbered.

Of the truth of this I am convinced by the rapid progress the disease is making. It is my desire, therefore, to wish you all a sincere and hearty farewell!

I want you to know that I am leaving this life in unspeakable happiness, because I rest my soul on my Saviour, trusting only and entirely to the merits of the great Atonement, by which my sins (and yours) have been put away for ever.

Dear Boys, I ask you to give your hearts to Christ, and earnestly pray that all of you may meet me in Heaven.

Then follows the signature, traced twice over, and neither quite perfect, in a trembling hand, whose life-work was evidently done.

This touching letter, it will be seen, bears date August 2nd. On the 3rd he was hardly conscious, and on the two following days, though apparently able to recognise his family, he was not able to make himself understood. On the evening of the 5th he passed away. To such a letter, written at such a time, it were almost an impertinent intrusion to add any words of ours. We lay it rather, with bowed head and reverent hands, before our readers, and leave it to speak its own noble message straight home to their hearts.

It may be well to mention that the accompanying portrait of the deceased, to which Mr. Overend, at our suggestion, has supplied a memorial frame, is engraved from a recent photograph, which, both in Mr. Kingston's opinion and ours, was the best he had ever had taken. The choice lay between this and one for which he sat some few years ago, but we naturally decided on the more recent, not only as being the better of the two, but also as the latest.

Bibliography

"The Late W.H.G. Kingston, 1814-1880." Boys Own Paper 11 September 1880: 796-97. Internet Archive. Web. 1 August 2025.

Created 1 August 2025