On Friday, 13 July 1877, Gaskell accompanied James to the historic border towns of Ludlow in south Shropshire, and Shrewsbury, the Salopian capital, both famed for their timber-framed buildings, cobbled streets, alley ways, historic churches and castles. They also stopped at the village of Stokesay, nestling in the Onny valley, with its impressive castle, one of the earliest fortified mansions of the thirteenth century, and large timber-framed Tudor gatehouse, surrounded by a deep, wide moat. We do not know the order of their itinerary, nor the kind of transport used, but all of these places were easily accessible at that time by rail from Much Wenlock, thanks to the efforts of Penny Brookes and other prominent local people. A straightforward round trip of approximately sixty-five miles would have been the following: Much Wenlock to Shrewsbury via Buildwas (change); Shrewsbury to Craven Arms (for Stokesay); Craven Arms to Ludlow; returning from Ludlow to Craven Arms (change) where they could take a direct train to Much Wenlock. James summarised the day in his letter to Adams: 'The morning after my arrival, luckily, Gaskell & I started off & made an heroic day of it – a day I shall always remember most tenderly. We went to Ludlow, to Stokesay & to Shrewsbury & we saw them all in perfection' (Monteiro 42). James's only other comment about Shrewsbury, the birthplace of Charles Darwin, was that it was "most capital".

Stokesay "A Gem"

Left: The Gatehouse and Well, Stokesay Castle. Right: The Hall. Stokesay Castle. Both courtesy of Julia Couchman. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Henry Adams had given James lots of information about Shropshire and had told him "not to fail [...] to go to Stokesay and two or three other places [in the neighbourhood where] Edward IV and Elizabeth are still hanging about" (Portraits 241). Adams would have been pleased to receive James's report of his immense enjoyment: "You spoke of Stokesay, & I found it of course a gem. We lay there on the grass in the delicious little préau, beside the wall, with every feature of the old place still solid & vivid around us, & I don't think that, as a sensation, I ever dropped back, for an hour, more effectually into the past. Ludlow, too, is quite incomparable & Shrewsbury most capital. The whole thing made a delightful day" (Monteiro 42).

Left: The New Tower, Stokesay Castle. "The stonework of this tower was built by Lawrence of Ludlow, who in 1290 began the work of turning Stokesay manor house into a castle." Right: The Gate House. "This picturesque black and white Elizabethan structure replaces the original 13th century gate house. The old defensive walls of the castle have practically disappeared". Photographs by Francis Firth and Co. From C. W. Airne, Castles of Britain (Manchester: Sankey, Hudson & Co., n.d.) courtesy of the Internet Archive, which digitized a copy of the book in the Getty Research Institute.

Adams would have been even more delighted to identify himself as "a friend of mine, an American", and to read of James's intense response to Stokesay (and other places) in his essay "Abbeys and Castles" published later that year.

Gaskell and James were following in the footsteps of John Ruskin who had also alighted at Craven Arms railway junction and walked about a mile to Stokesay in 1863. Confusing the name of the place as "Bishop's castle", – a real town named Bishop's Castle exists a few miles away – Ruskin wrote to his father that Stokesay was "one of quite the finest things I have ever seen – a ruined farmhouse and castle – both of marvellous richness in their way, carved wood, and stone: and pretty brook windings and hills about them" (Winnington Letters, 456; Thanks to B Richards for drawing my attention to this letter). In a letter to Margaret Bell of 19 March 1864, Ruskin made explanatory sketches of Craven Arms railway station, of the road leading to Craven Arms and of the road leading to Stokesay castle, vignettes most probably of sketches he made in 1863 (Winnington Letters, 484).

The Stokesay Churchyard. Photograph by the author 2005.

Near the church at Stokesay, Gaskell and James turned into a narrow path in the churchyard with holly trees and ancient yews. There they were among monuments made of sandstone, granite, limestone, polished black marble, and a variety of memorials – chest tombs, altar tombs, standing gravestones. The little church of St John the Baptist, with its castellated square tower, was founded in the twelfth century and rebuilt in the seventeenth century owing to extensive damage in the Civil War. At the time of James's visit, the vicar was the Rev. James Digues La Touche (1824-1899), an enthusiastic, knowledgeable, amateur naturalist, geologist and historian.

The Medieval Well mentioned by James in Portraits of Places. Photographs by the author.

On approaching the castle grounds, adjoining the churchyard, they crossed a little bridge over "a good deep moat, now filled with wild verdure", went through the large oak, nail-studded gatehouse door, then entered the inner courtyard. There they lay, stretched out on a warm summer's day on that "grassy, aesthetic spot" (Portraits 243): "a couple of gentlemen in search of impressions [...] one of whom has taken a wine-flask out of his pocket and has coloured the clear water drawn for them out of the well in a couple of tumblers by a decent, rosy, smiling, talking, old woman, who has come bustling out of the gatehouse, and who has a large, dropsical, innocent husband standing about on crutches in the sun" (242). The two well-dressed city gents, enjoying their claret diluted with water from the medieval well, speaking with accents that set them apart as foreigners from America and London, attracted the curiosity of the incongruous couple – the talkative, bustling housekeeper and her uncommunicative, sickly husband. James's attempt to converse with him and enquire about his health met with silence and a stony stare.

Since 1992, Stokesay Castle has been under the guardianship of English Heritage and has been open to the public. But at the time of James's visit, it was in private hands and had been purchased in 1869 by John Derby Allcroft (1822-1893). Allcroft owed his fortune to the success of his London business, making and selling ladies' leather gloves, essential articles of clothing in a Victorian lady's wardrobe. Allcroft was a philanthropist and gave large sums of money to charities. He also gave freely of his time as Treasurer of Christ's Hospital, a boys' school in Newgate Street, London: Ruskin was a governor of the school. When Ruskin gave an address, "A Lecture on Stones", to the boys in April 1876, Allcroft proposed a vote of thanks (Works, 26.565n3). According to Kelly’s Shropshire (1900), from 1873 and for the next twenty years until his death, Allcroft devoted himself to the repair and restoration of Stokesay, "at very considerable expense and with much skill and judgment" (250), a task continued by the Allcroft family who opened the Castle to the public in 1908. Allcroft also built for himself a splendid country mansion called Stokesay Court (approximately two miles south of Stokesay Castle in the village of Onibury), designed by architect Thomas Harris (1829/30-1900) and completed in 1892.

Unlike Ruskin, who generally avoids any mention of the human presence in his sketches of cathedrals and churches, James needs, even craves, a picturesque scene. On his little tour of France in 1882, he wrote: "I stopped at Beaune in pursuit of the picturesque" (A Little Tour of France 321). He found that at Stokesay. Although, as James tells us in Portraits of Places, the rooms in the uninhabited castle – in which no one had lived since Queen Anne's time – were "in a state of extreme decay" (242), a male artist was "reproducing its mouldering repose". Outside, a young, female artist was also at work: "From one of the windows I see a young lady sitting under a tree, across a meadow, with her knees up, dipping something into her mouth. It is a camel's hair paint-brush; [...]. These are the only besiegers to which the place is exposed now, and they can do no great harm, as I doubt whether the young lady's aim is very good" (242).

They gazed at the gables of the great Banqueting Hall with mullion windows flanked by massive buttresses against the solid, thick stonewalls of this "small gentilhommière of the thirteenth century". James became totally absorbed in the past, crossing the centuries: "I have rarely had, for a couple of hours, the sensation of dropping back personally into the past in a higher degree than while I lay on the grass beside the well in the little sunny court of this small castle, and lazily appreciated the still definite details of mediæval life" (242).

James was particularly struck by the incongruity of the "curious gatehouse of a much later period" and the "fortress": "This gate-house, which is not in the least in the style of the habitation, but gabled and heavily timbered, with quaint cross-beams protruding from surfaces of coarse white plaster, is a very effective anomaly in regard to the little gray fortress on the other side of the court" (241).

It is through the observation of an architectural detail – the castle's unusually large windows, instead of the more secure, narrow protective slits associated with defences – that James constructs the genteel life of its former inhabitants. "The fortress", he observes, "must have assumed its present shape at a time when people had ceased to peer through narrow slits at possible besiegers. There are slits in the outer walls for such peering, but they are noticeably broad and not particularly oblique, and might easily have been applied to the uses of a peaceful parley". This contributes to the "charm of the place; [when] human life there must have lost an earlier grimness [and] was lived in by people who were beginning to believe in good intentions".

James and Gaskell "wandered about the empty interior, thinking it a pity such things should fall to pieces". They went in the "beautiful great hall [...] with tall, ecclesiastical-looking windows, and a long staircase at one end, climbing against the wall into a spacious bedroom" (242). The room at the top of the staircase, with its "irregular shape, its low-browed ceiling, its cupboards in the walls, and its deep bay windows formed of a series of small lattices" (242-43) was particularly evocative of the past.

"The platform of the staircase". Photograph by the author 2005.

It stimulated James's imagination and from it he recreated what he called "the historic vision": "You can", he continued, "fancy people stepping out from it upon the platform of the staircase, whose rugged wooden logs, by way of steps, and solid, deeply-guttered hand-rail, still remain" (243). From that vantage point, "they looked down into the hall, where [...] there was always a congregation of retainers, much lounging and waiting and passing to and fro, with a door open into the court". It was the ideal place from which the lord and lady of the house could view festivities in the court below – "groups on the floor [...], the calling up and down, the oaken tables spread, and the brazier in the middle" – and if necessary issue orders. But the courtyard in the middle ages was a rough terrain, not grassy and soft: "there were beasts tethered in it, and hustling men-at-arms, and the earth was trampled into puddles." James's 'historic vision' became more complete as he pursued it through the rest of the building, "through the portion which connected the great hall with the tower [...] through the dusky, roughly circular rooms of the tower itself, and up the corkscrew staircase of the same to that most charming part of every old castle, where visions must leap away off the battlements to elude you – the bright, dizzy platform at the tower-top, the place where the castle-standard hung and the vigilant inmates surveyed the approaches". The past becomes present again. In a final flourish of the pen, Stokesay Castle is anthropomorphised – it becomes a trapped animal of the chase – thereby enabling James to grasp, possess and appropriate it more easily: "Here, always, you really overtake the impression of the place – here, in the sunny stillness, it seems to pause, panting a little, and give itself up." He has at last totally absorbed what he calls "the aesthetic presence of the past" (quoted Tanner 158-59). His feelings were an extension of those exuberant words he uttered in his letter of 1 November 1875, to his family, shortly after arriving in London from America: "I take possession of the old world – I inhale it – I appropriate it! I have been in it now these twenty-four hours [...] and feel as if I had been here for ten years" (Life 2.484)

In 1882, James visited Aigues-Mortes ("Dead Waters"), the curiously named walled town on the edge of the marshy Camargue on the delta of the river Rhone in the south of France. Although his impressions are much less personal and less dramatic that those of Shropshire, when concluding his visit, he climbed the thirty-metre-high fortress Tour de Constance and, as he explains in A Little Tour in France, experienced similar feelings of possession-taking: "From the battlements at the top, [...] you see the little compact rectangular town, which looks hardly bigger than a garden-patch, mapped out beneath you, and follow the plain configuration of its defences. You take possession of it, and you feel that you will remember it always" (225).

Ludlow

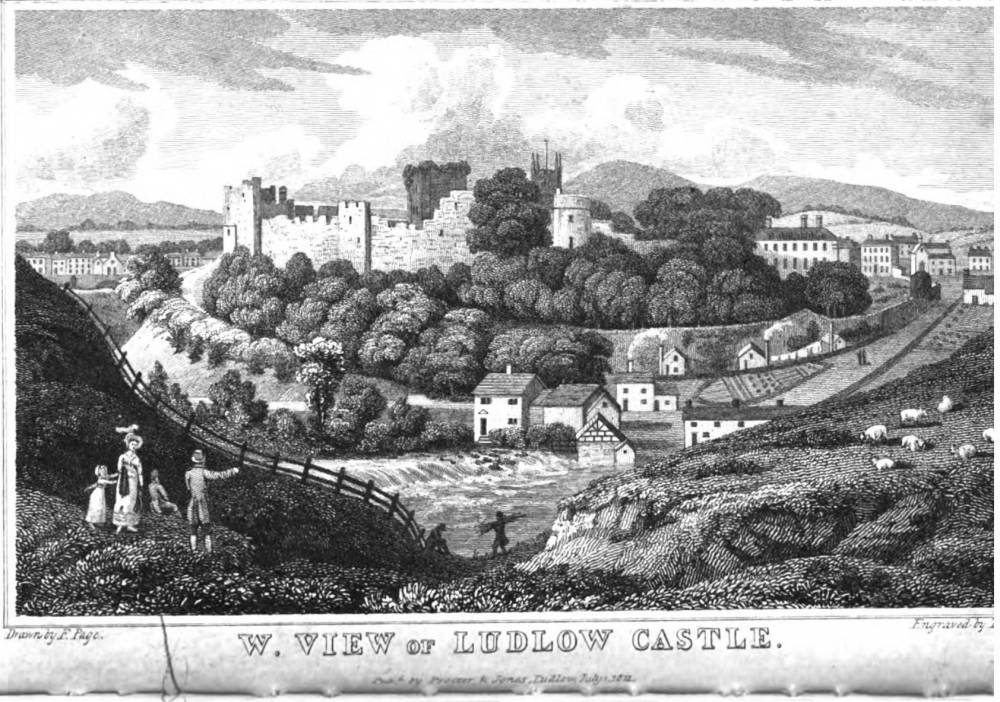

Ludlow Castle

Ludlow is situated about six miles south east of Stokesay. Its fortress castle was strategically built on the highest point of the town, originally to fend off the then hostile Welsh. Its other important landmark is the pink sandstone church of St Laurence, the largest parish church in Shropshire and known as the "cathedral of Shropshire". In the wooded valley the gentle river Teme partly encircles Ludlow before continuing on its seventy-five-mile journey from the hills on the Welsh border to Powick in Worcestershire where it joins the river Severn.

Ludlow railway station opened in 1852, due in large measure to the engineering skills of Thomas Brassey (1805-1870), complete with a gabled station master's house, passengers' waiting-rooms and other facilities. On arrival, Gaskell and James walked up some steps and as they crossed the footbridge over the railway line, they saw in the distance St Laurence's Church. Its pinnacled, lofty square tower, one hundred and thirty-five feet high, rebuilt in the fifteenth century in the perpendicular style, dominated the town. The visitors would have many opportunities to hear the famous eight bells in the tower chime with their different melodies. They walked along Station Drive, then turned left into Corve Street, a mainly residential area with stately, solid, Georgian brick houses and inviting doorways enhanced with elegant pediments and traceries. Gaskell and James became increasingly aware that they were in a hilltown for as they approached the Bull Ring the gradient was noticeably steeper. On their left, in Corve Street, they admired the richly decorated, timber-framed Feathers Hotel of 1603, and facing it, the Bull Hotel. They turned right into King Street, past St Laurence's, and continued up a gentle slope, along the historic High Street that opened into Castle Square, a bustling market place in the shadow of the castle.

Left: . Right: . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

They then made their way to the castle, whose solidity was painted by Turner on several occasions as a picturesque scene. It was here in the great council chamber that John Milton's Masque of Comus was first performed in 1634. This was a revelry starring Comus a pagan god of Milton's invention, written specially for the Earl of Bridgewater to celebrate his appointment as Lord President of the Council of the Marches, the governing body for the border counties (known as Marches), with the seat of power at Ludlow Castle. The tradition of a performance of Comus in the castle, usually in the open air, has continued for centuries. Ludlow Castle had many royal connections. Young Prince Edward (the uncrowned King Edward V) spent much of his childhood there, before his imprisonment and subsequent death in the Tower of London in 1483. This was a story that James had learnt about from Delaroche's painting when he first visited the Louvre in 1855. The seventeen-year-old Catherine of Aragon once lived in the castle for five months with her fifteen-year-old husband Prince Arthur (son of King Henry VII) until his death from consumption in 1502. She later married her husband's brother, King Henry VIII. Another royal visitor was Queen Mary Tudor who spent three winters at Ludlow between 1525 and 1528. In the late seventeenth century the castle was abandoned and fell into decay. It was not until 1811 that it was rescued and purchased by the 2nd Earl of Powis: it remains in the ownership of that same family in the twenty-first century.

Left: . Right: . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

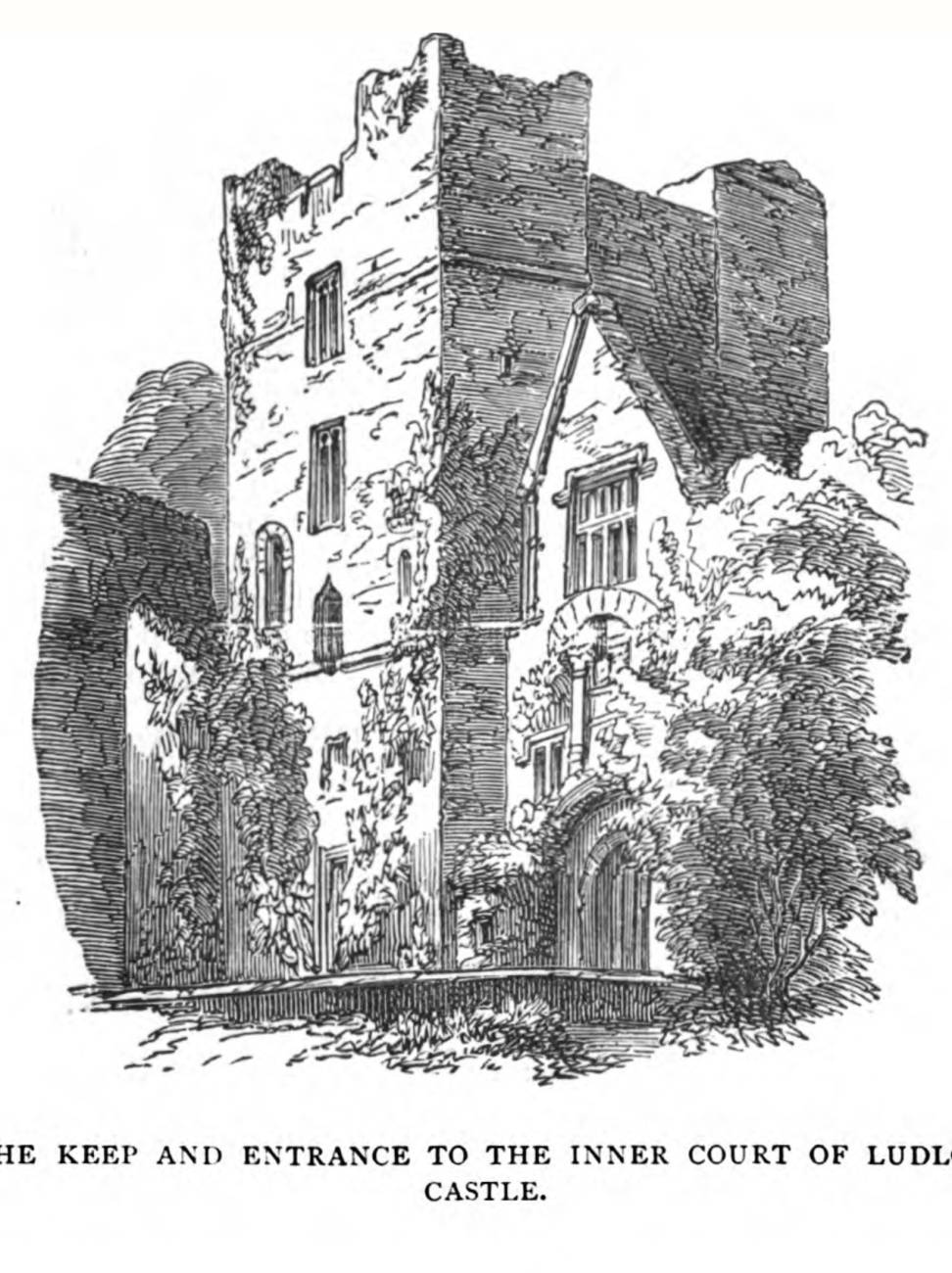

Gaskell, a man of exquisite courtesy, would almost certainly have contacted the Earl of Powis prior to the visit, but James does not mention meeting the owner or members of his family or indeed anyone else. They entered via the Principal Gateway in the outside curtain wall, crossed the castle yard or outer bailey and made their way to the little two-arched stone bridge over the dry, deep moat. Once through the massive studded oak door at Sir Henry Sidney's gateway, they stepped into the heart of the fortress, the inner bailey, also protected by a thick curtain wall. There they walked among the ruined remains of the little round chapel of St Mary Magdalene, the Great Hall or council chamber some sixty feet long and thirty feet wide, private apartments, kitchens, towers and other buildings. But it was the oldest part of the castle, the massive Norman keep, seventy-feet high, that James wished to experience most of all. They entered through a low doorway immediately to the left of the entrance to the inner bailey, and climbed the steep, winding eight-hundred-year-old steps, peering at times through the slits hewed through the four-feet-thick wall. They paused on the platforms marking the storeys, until eventually reaching the summit crowned with battlements and all open to the sky. The magnificent countryside of Shropshire with the Wrekin to the north stretched far into the horizon: the Clee Hills stood out in the east, and nearer was wooded Whitcliffe Common and Dinham Bridge over the Teme in the west. The church of St Laurence and the medieval grid town of Ludlow nestled in the south east corner.

Left: . Right: . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

James was again in search of impressions, sensations and pulsations, and from that lofty vantage point he lingered in order "to enjoy the complete impression so overtaken" (Portraits 243). Similarly, at Stokesay, he had positioned himself on a "platform at the tower-top" in order to "really overtake the impression of the place" (not forgetting the vantage point of Wenlock Edge). James was experiencing at first hand what he would develop as a recurring theme in his fiction, that of the protagonist observing from a privileged viewpoint such as a balcony or other height. In The Turn of the Screw, little Flora takes her new governess on a tour of Bly "through empty chambers and dull corridors, on crooked staircases", but on reaching "the summit of an old machicolated square tower", the governess feels dizzy (155). This is a premonition of its significance later in the story, for the first terrifying apparition of the ghostly figure of the dead servant Peter Quint takes place high up at the very top of a square, crenellated tower among the battlements. As the governess observer-narrator confronts the past, the experience intensifies as the man stares at her, then moves to another crenellation, continues to pierce her with his eyes until he eventually turns away and disappears. The observer-writer experiences some of her/his most powerful emotions, "the whole feeling of the moment returns" intensified by the silence of the cawing rooks and the realisation that the scene was "stricken with death" (164). The medieval border castles of Ludlow and Stokesay provided James with possible models for Bly.

But away from the fortress castle, it was elegant Georgian centre of Ludlow, so rich in literary, artistic and musical activities that suited James. The carefully planned town was the exemplar of the setting for the novels of those quintessential English writers, Frances (Fanny) Burney – whose father Charles Burney was born in Shrewsbury and studied music there – and Jane Austen. It was a place where their heroines "might perfectly well have had their first love-affair", and to which a journey "would certainly have been a great event to Fanny Price or Emma Woodhouse, or even to those more exalted young ladies, Evelina and Cecilia" (Portraits 244. James refers to Fanny Price and Emma Woodhouse, heroines of Jane Austen's Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1816), while Evelina and Cecilia are the heroines of Burney's novels of those names.). It is "a place on which a provincial 'gentry' has left a sensible stamp". Seldom had Henry James seen "so good a collection of houses of the period between the elder picturesqueness and the modern baldness". The sight of these dwellings transports him to a pre-Victorian age, to a more insular English society with its traditions and its "narrowness of custom". In short, a non-cosmopolitan society that James, "a stranger", would, he recognises, have had difficulty in penetrating, not only in London but also in the provinces and in "a genteel little city like the one I am speaking of" (Portraits 245).

James delights in being transported to this "most impressive and magnificent of ruins" that has remained intact and untouched by industrialisation and retains "a remarkable air of civic dignity". "Ludlow is", he writes, "an excellent example of a small English provincial town that has not been soiled and disfigured by industry: it exhibits no tall chimneys and smoke-streamers, with their attendant purlieus and slums" (Portraits 244). The effects of good town planning, as well as the care people take in maintaining standards, are noticeable: "its streets are wide and clean, empty and a little grass-grown, and bordered with spacious, mildly-ornamental brick houses, which look as if there had been more going on in them in the first decade of the century than there is in the present, but which can still, nevertheless, hold up their heads and keep their window-panes clear, their knockers brilliant and their door steps whitened." Everything suggests to James that this was a very good "centre of a large provincial society" (244).

In a pre-railway age, James imagines society arriving for the season "in rumbling coaches and heavy curricles" to enjoy the abundance of cultural and social activities such as "balls at the assembly rooms". Assembly Rooms, mainly places for fashionable gatherings, were immensely popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: those to which James alludes date from 1840 and occupy a site on the corner of Mill Street and Castle Street in the town centre.

Celebrities left behind the London stage and flocked to perform in Ludlow: "Mrs Siddons to play" and her friend the renowned Italian soprano Angelica Catalani "to sing". The reference to the great English actress Sarah Siddons had a particular resonance for James for he knew her niece, Fanny Kemble, whom he described in A Small Boy and Others as "my fine old friend" (Small Boy 167). He also knew Adelaide Sartoris (Sarah Siddons's sister) and her daughter (Life 2.160). James adored the theatre from a very early age, and indeed wrote several plays. He was fascinated with Georgian England and admired the strong role and success of Mrs Siddons, immortalised in portraits by Gainsborough and Reynolds. In his short story The Aspern Papers, astonishment that the elderly English lady Miss Juliana Bordereau, the former lover of the great American poet Jeffrey Aspern and keeper of his valuable manuscripts, is alive in Venice is equal to that of learning that Mrs Siddons (or Queen Caroline or Lady Hamilton) still existed (47). Sarah Siddons and her actor husband William were on stage for three consecutive nights, 15-17 August 1803, at Ludlow Theatre. She played the role of Desdemona, and her husband that of Iago in the first Ludlow performance of Shakespeare's tragedy Othello on Monday 15 August 1803. On Tuesday 16 August, sandwiched between Othello and Hamlet, they starred in The Mountaineers by George Colman "the Younger" (1762-1836), and in Deuce is in him, a two-act farce by his father, George Colman "the Elder" (1732-1794). In the grand finale in their honour on Wednesday 17 August, Mrs Siddons played Ophelia, and Mr Siddons was cast as Hamlet. A poster advertising these performances is preserved in Ludlow Museum and it is not inconceivable that James, seventy-four years later, visited the museum and obtained this information from that source.

Angelica Catalani (1780-1849), known as "Mme Cat" or "Mme Catalani", was the convent-educated daughter of a tradesman from Sinigaglia on Italy's Adriatic coast who became one of the most famous prima donnas of her day. One of her memorable operatic performances in London was on 3 July 1813 when news was announced of Wellington's victory at the battle of Vittoria. Madame de Staël, who was present on that occasion, reported that Catalani's rendering of "God save the King" caused all the ladies to rise to their feet and pray for their country (Fairweather 419).

Last modified 12 March 2020