rank Harris, an unsavoury Victorian, upset Housman. Housman, he'd assumed, shared his opinions and had therefore mocked Queen, country, and the Shropshire Light Infantry in his poetry. 'I didn't, and I don't,' Housman told him, angrily. The Frank Harris-type of intellectual is still with us — now in the ascendancy — and still getting Housman's kind of simplicity wrong. Housman was a very intelligent man, too, but cleverness doesn't have to exclude the simple. His poetry, and the reasons for writing it, are easy to understand although there is, I think, great depth in it as well.

rank Harris, an unsavoury Victorian, upset Housman. Housman, he'd assumed, shared his opinions and had therefore mocked Queen, country, and the Shropshire Light Infantry in his poetry. 'I didn't, and I don't,' Housman told him, angrily. The Frank Harris-type of intellectual is still with us — now in the ascendancy — and still getting Housman's kind of simplicity wrong. Housman was a very intelligent man, too, but cleverness doesn't have to exclude the simple. His poetry, and the reasons for writing it, are easy to understand although there is, I think, great depth in it as well.

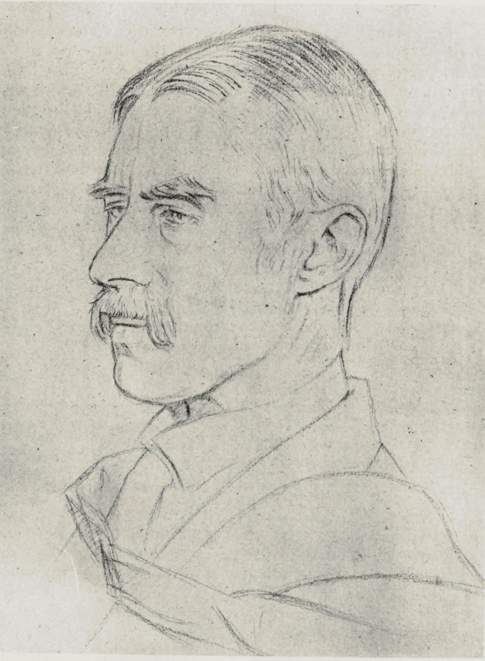

A. E. Housman by William Rothenstein. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Larkin called Housman the poet of unhappiness. More aptly perhaps he is the poet of pain. Or, better still, depression. He said poetry came to him when he was unwell or morbid; it was like the pearl in the oyster. The causes of that pain are well known. To begin with, he'd been damaged by his mother's death when he was twelve. She died of breast cancer after being bed-ridden for a year or so. Her husband was too feeble to be of comfort, and she seems to have leaned heavily on her eldest son, who was too young to carry her pain.

The other reasons are more complex. He began A Shropshire Lad around 1890 while clerking in the Patent Office. A third of the sixty-three poems, however, were written in a state of continual excitement, as he put it, in early 1895 and that was the time of Oscar Wilde's trial. He'd already fallen in love for the first and only time with the least suitable person on earth. Moses Jackson was completely heterosexual. Housman was not and he must already have known he faced a lifetime of loss and loneliness. The Wilde conviction brought home to him that his countrymen didn't like what he was, and that he would have to live in hiding for the rest of his life. His was a double exile.

I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made. [Last Poems XII]

Perhaps the pain was so unbearable that only words could ease it. (It's not uncommon; poetry can be an ointment for the troubled mind.) Proof of this may lie in the fact that over the next quarter century he wrote only spasmodically. Sometimes a year went by without a poem being written at all. In other years, perhaps there were only two or three. Then, in 1922, came another spike of activity — in ten days he filled fifty seven pages of a notebook. The anguish this time was caused by the knowledge that Moses Jackson was dying of cancer. Last Poems was partly written at the time, partly collated from pieces written as long ago as the 1890s. A copy was rushed to Jackson as he lay dying in Vancouver.

Adolescent, rather than a poet of pain or depression, is what Housman's most commonly called. Adolescent because it's immature to carry the sorrow of loss into old age. You're supposed to grow out of it. And his emotions are narrow — stultifying if not stunted — and there is, of course, another way of being. Housman tells us his life's work was to discover the truth, to know things as they are. But perpetual sadness is not the only way things are. Where he saw an emptiness at the heart of things, others see a fullness. Yet to have experienced that he may have needed reciprocated love. Love, after all, is the deepest thing we can know.

People also remark on the narrowness of his range: beer and betrayal, the gallows and the grave, Redcoats dying on the edge of Empire. One reason — perhaps a trivial one — is that Housman is a page-turner; you notice the narrowness because you rarely read one poem and stop. The reason for this is his clarity and brevity. Prosodically his work is simple — mainly quatrains or cinquains in iambic tetrameters or trimeters with variations on strong AABB or ABAB rhymes. Many people despise this (Edith Sitwell did) but it can make for clarity and brevity and, in turn, readability.

He also had a way with words. Sometimes half the mind looks down on them, while the other half laps them up. "The Land of Biscay" has a typical Housman theme. The poet and grief are on the shore of the Bay. A golden ship is sailing in. They hope to board and cross the ocean to happiness. But the helmsman is as depressed as they are. There is, says the message, no escape.

Looking from the land of Biscay

over Ocean to the sky

On the far-beholding foreland

paced at even grief and I.

There, as warm the west was burning

and the east uncoloured cold,

Down the waterway of sunset

drove to shore a ship of gold.

Gold of mast and gold of cordage,

gold of sail to sight was she,

And she glassed her ensign golden

in the waters of the sea.

. . . .

Under hill she neared the harbour,

till the gazer could behold

On the golden deck the steersman

standing at the helm of gold,

Man and ship and sky and water

burning in a single flame;

And the mariner of Ocean,

he was calling as he came:

From the highway of the sunset

he was shouting on the sea,

'Landsman of the land of Biscay,

have you help for grief and me?' [More Poems XLVI]

It shouldn't work, but it does. It's easy to write English badly, hard to write it well, but this has a Chaucerian clarity and openness of vowels. The alliteration in the first stanza itself adds to the poem's meaning. (It gladdens.) The second stanza has no alliteration but the words open out like a man calling across the water of the sea. You're left with both scorn and delight bobbing around in the mind. For some people it may be too embarrassing. It's easier to feel ashamed and condemn the work. But in all honesty an emotional charge is being passed across.

And Housman himself said a poem exists solely to transmit emotion. It can work even if you disagree with the thoughts being expressed; the meaning may be unwelcome but the poem can still pass on the emotion the poet felt. It can also be meaningless and still work; too much meaning, in fact, can get in the way. Most eighteenth-century poetry was sham because it was thought-based and not emotion-transmitting. Blake was supreme because he was all feeling and little intellect.

Housman also said that the ability to criticise poetry is rare. He didn't have it, so it seems a bit vainglorious to try it on with him. Somewhere Larkin tells the story of an encounter with a student. Was she enjoying the poem she was reading? Poetry is not for enjoyment, she told him rather snappishly, it's for analysing. Well, there isn't much in Housman for her to exegete.

Critics therefore often seem to try too hard. Orwell saw him through a veil of Socialist ideology; he appealed to, he said, only to rentiers pining for country estates, or ex-Servicemen (after the Great War) in rebellion against their elders, or public schoolboys tormented by deviant masters. Another critic sees in him the atomic theory of Democritus as filtered through Epicurus and Lucretius. The Roman at Wenlock Edge was a collocation of atoms, broken down and reassembled as a Victorian yeoman.

On Wenlock Edge the wood's in trouble;

His forest fleece the Wrekin heaves;

The gale, it plies the saplings double,

And thick on Severn snow the leaves.

'Twould blow like this through holt and hanger

When Uricon the city stood:

'Tis the old wind in the old anger,

But then it threshed another wood.

Then, 'twas before my time, the Roman

At yonder heaving hill would stare:

The blood that warms an English yeoman,

The thoughts that hurt him, they were there.

Occam's Razor suggests something simpler: history fountaining through us. It was not the material atoms of the Roman that survived; it is the past carried by immaterial thought. At one time the past was always close and alive in England, though not now. This was a man-made landscape and Auden coined a word — topophilia — to describe a love of it; not of a wilderness, but of a place shaped and softened by human hands. Somewhere James Lovelock, the Gaia man, reminds us that men once made a garden of a country: England. You had to be there to know it, and it has long since passed away.

For some, at least, to be English in those days, to be steeped in its landscape, was to have a spiritual experience. For some, at least, Housman created a landscape capable of evoking that kind of Englishness. His Shropshire may be mythical but myth tells a truth that can't always be told in any other way.

On the idle hill of summer,

Sleepy with the flow of streams,

Far I hear the steady drummer

Drumming like a noise in dreams. [A Shropshire Lad XXXV]

In summertime on Bredon

The bells they sound so clear;

Round both the shires they ring them

In steeples far and near. [A Shropshire Lad XXI]

Is this too fanciful? Too personal a view? Perhaps not. Roger Scruton — too young to have experienced this sense of spirituality for himself — nevertheless wrote a book about it: England, An Elegy. England, he argues, was a home, rather than a nation. It was the Motherland whose laws, customs, habits and institutions — from clubs to schools to regiments — evolved to let strangers live together in a common home. To be English, then, was to feel you were spiritually where you belonged. And Housman evokes it.

He may never have felt this way himself or, if he did, never made the connection with that sense of something greater than the self at large in the world. He missed out, therefore, both on human love and on a feeling that there is something greater than sorrow in the cosmos. His verse, if that is true, is really a poetry of unnecessary loss.

Last modified 8 June 2007