eorge Eliot does not regard the novel as a vehicle for entertainment alone, but rather as a means of revealing the human condition. Like George Meredith, "she is the embodiment of philosophy in fiction," as Oscar Wilde remarked in 1897. Virginia Wolfe called Eliot's Middlemarch "one of the few English novels for grown-up people." Mary Ann Evans was twelve at the time of the Great Reform Bill (1832), which forms the historical context of Middlemarch.

eorge Eliot does not regard the novel as a vehicle for entertainment alone, but rather as a means of revealing the human condition. Like George Meredith, "she is the embodiment of philosophy in fiction," as Oscar Wilde remarked in 1897. Virginia Wolfe called Eliot's Middlemarch "one of the few English novels for grown-up people." Mary Ann Evans was twelve at the time of the Great Reform Bill (1832), which forms the historical context of Middlemarch.

Mary Ann Evans, born in 1819 at Arbory Park ("Griff") in Astley near Coventry, was the gifted daughter of Robert Evans, the Warwickshire estate agent for the Earl of Lonsdale and the model for such yeoman characters as Adam Bede (which was Charles Dickens's nickname for the novelist from 1859). By his previous marriage Evans had an older daughter and a son. At her mother's death in 1836 Marion was the only woman in the house, at which point she became her father's housekeeper. Politically and socially conservative, Robert Evans advocated outward religious conformity for Marion, who was swept up by Nonconformist thinking, even though he was not particularly religious. Through the influence of her schoolmistress, Marion for a time was an enthusiastic Evangelical who favoured Jean Calvin's Doctrine of the Elect. Marion's maternal aunt was a Wesleyan (Methodist) who communicated her belief in good works, a doctrine of personal salvation that contradicts Calvinism. When her father retired in 1841, her brother Isaac was given the agency, and she and her father moved to a house in Coventry. Here she joined a group of intellectuals such as Charles Bray in their historical study of the Bible. Under their influence and through her own reading, Marion grew skeptical. Conflict with her father arose when she refused to attend regular Anglican Church worship any longer. However, after some argument she gave in. She faithfully tended house for her father until his death in 1849. Now thirty years old, she was considered long past the normal age for marriage. In her father's will she received an annuity of £100 which gave her a certain independence. Her religious skepticism was tempered by her recognition that her father had simply been too old to alter his views. But gradually she developed, despite her outward conformity in the 1840s, a sympathy with any religion that could offer solace for human sorrows.

In 1850, she travelled on the Continent for the first time, in company with the Brays; upon her return to England, she began writing for the prestigious Westminster Review, for which she became assistant editor in 1851. Now a member of a London literary circle that included Herbert Spencer and George Henry Lewes, she translated Feuerbach's Essence of Christianity from German (1854)--the only book to bear her real name. About this time, she entered into a common-law relationship with her editor, Henry Lewes, whose wife had abandoned him and their three children for an extra-marital affair.

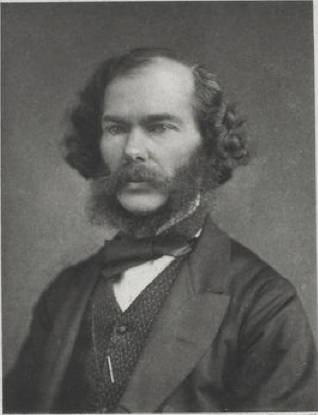

Left: George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), etching by Stephen Alonzo Schoff (1818-1904) inscribed "Regents Park, Dec. 19, 1879. To Mrs. (Anthony) Trollope." From the Berg Collection, New York Public Library (image id nos. 483034 and 483502). Right: George Henry Lewes, a photograph by Elliott & Fry and engraved by Swan Electric Engraving Co. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Mary Ann's rejection by her friends and family over her common-law marriage with Lewes is reflected in The Mill on the Floss (1860). Lewes deeply sympathized with Mary Ann's personal, intellectual, and artistic struggles. It was he who first encouraged her to write fiction: Scenes from Clerical Life, serialized in Blackwood's Magazine (1857). He provided her with material, and edited her work. He was a 'Positivist' — a follower of the philosophy of August Comte, who had postulated that there had been three hierarchical ages (animistic, metaphysical, and positivistic = truth from examination of facts). That a new author of great power had emerged was confirmed by the enormously popular Adam Bede (1859).

Her perceptive and pointed criticisms of Austen and Dickens are close to modern attitudes. And yet her literary intentions included appreciation of goodness, perception of reality, and precision of expression (both for herself and her reader). She admired the simple, homely style of the early Flemish painters such as Breughel, a taste which is reflected in such 'Dutch' interior scenes as the harvest supper in Adam Bede, Chapter 17, in which she extols the works of the seventeenth-century Dutch masters. She attacked literary conventions in character delineation and typing, stereotypical plotting, and use of setting as mere backdrop. Adam Bede demonstrates Eliot's belief that art should be modeled on life, not on other works of art. Her theme is that happiness is the reward life gives for tolerance, compassion, and understanding (as it is for Dinah Morris and Adam), and that over-riding ambition, thoughtlessness about the welfare of others, and greed \cannot bring such happiness. Through her plots and characters Eliot preaches that working only for self-gratification- is dangerous to one's spirit because it precludes learning from experience and developing one's character. In her stories she studies the impact of environment, including the social environment, on the individual; consequently, she strives to render her settings more realistic and believable through telling details and dialect.

Created 18 February 2001; last modified 2 May 2025