Fourteen years after this contribution appeared on our site, the author writes with the good news that a revised version of the article, entitled "Meditations on Innocence in Little Nell's Deathbed Scene: Deconstructing Little Nell," has appeared in The Annals of Ovidius University. Philology Series (ISSN 1224-1768 (print); ISSN 2734-7060 (online); ISSN-L 1224-1768. The new version is available here: https://litere.univ-ovidius.ro/Anale/2025_volumul_1/sectiunea1/4.%20Boev%20Hristov.pdf

Setting the Scene

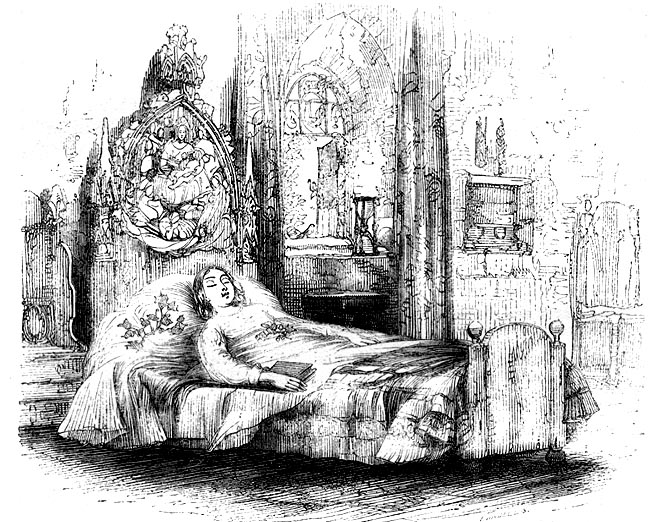

She was dead. No sleep so beautiful and calm, so free from trace of pain, so fair to look upon. She seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God, and waiting for the breath of life; not one who had lived and suffered death. Her couch was dressed with here and there some winter berries and green leaves, gathered in a spot she had been used to favour. "When I die, put near me something that has loved the light, and had the sky above it always." Those were her words.

She was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Nell was dead. Her little bird — a poor slight thing the pressure of a finger would have crushed — was stirring nimbly in its cage; and the strong heart of its child-mistress was mute and motionless for ever. Where were the traces of her early cares, her sufferings, and fatigues? All gone. Sorrow was dead indeed in her, but peace and perfect happiness were born; imaged in her tranquil beauty and profound repose.1 (Chapter LXXI, p.524)

I propose to examine a passage from one of the most famous scenes in the entire history of British Literature — Little Nell’s death. During almost 200 years since Dickens published The Old Curiosity Shop (1841), this passage has provoked passionate reactions, which started almost immediately after the novel appeared. Crowds of Americans anxiously waited at the docks for the ships coming from England to receive news from the novel’s next installment of the whereabouts and well-being of Little Nell, an angelic little girl, not yet fourteen, who fled London on a perilous journey into the countryside in the company of a mentally infirm grandfather with a passion for gambling. All the the good and evil forces in the novel pursued her, the former trying to save her from the clutches of the latter led by the grotesquely deformed money-lender, the dwarf Quilp. The Victorian reading public in general was deeply moved by the death of Little Nell. Although Dickens was inundated with letters imploring him to spare her and let her live, later dissenting voices — most famously the scathing criticism of Aldous Huxley, who referred to this passage in Vulgarity in Literature as “inept and vulgarly sentimental” (6) — attacked the scene. Oscar Wilde was famously quoted to have said that “one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without dissolving into tears . . . of laughter.” Twentieth - and twenty-first-century literary criticism, however, has pointed out possibilities for rehabilitating readings of this and similar passages by Dickens.

["At Rest (Nell dead)"] by George Cattermole. Since Dickens had complete editorial control over the illustrations of his novels on their first appearance, they often provide additional authorially approved information about the text and pictorial interpretation of it. [George P. Landow.]

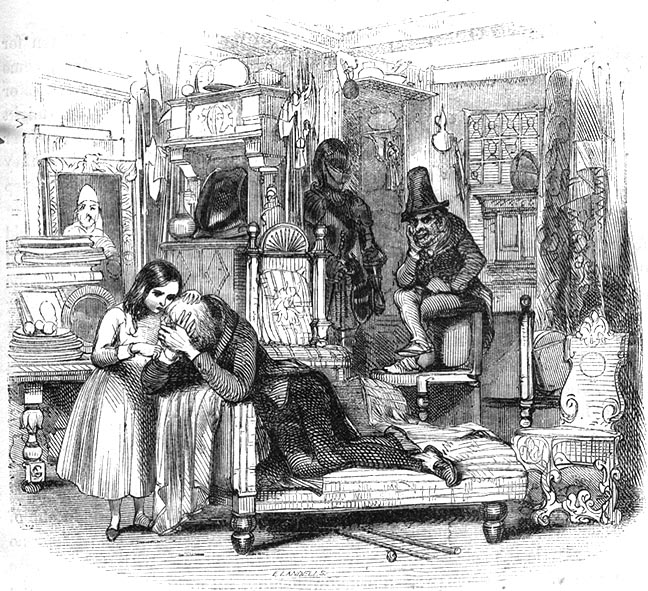

In his 1907 edition of The Old Curiosity Shop, G.K. Chesterton was one of the first to remind us that a definite artistic idea exists behind the death of Little Nell, an idea that accounts for the fact that Nell could not have been spared. Responding to Leavis’s indictment that Little Nell is nothing but “a contrived unreality” aiming to indulge in quenching the reader’s thirst for sentimentalism, John Bowen argues for allegorical interpretations of Little Nell’s character (14). The intense concentration of evil and ugliness in the total opposite of Little Nell, the dwarf — Quilp has not passed unobserved either, being condemned as politically incorrect and offensive to little, short, or handicapped people. This rather limited reading of Dickens leaves out a consideration for the Victorian sensibility as well as the fact that the reading public nowadays, unlike its Victorian counterpart, does not spend so much time reading, computers having invaded the lives of everyone in our age, including the people accustomed to reading books, thus even further distancing us from the reading reception Dickens necessitates. We might as well mention a Freudian approach to Little Nell in which sexuality is never stated but always present based on the idea that we can discover hidden truths deconstructing literary texts of which even the writers themselves were not conscious by exploring binary oppositions like the one of presence-absence.

In the following essay on Little Nell’s death scene, I shall also use an allegorical interpretation of Little Nell’s character in general and this scene in particular as well as the principles of deterritorrialization and reterritorialization as developed by Deleuze and Gautari in Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972-1980). My analysis suggests other possible interpretations deriving from the death scene's internal contradictions, and here I shall apply the ideas of deconstruction propounded by Derrida in Of Grammatology (1967). I defend the idea that scorning as mawkish certain passages by Dickens is just one way of reading them, since his texts presuppose a much bigger range of mutually exclusive interpretations.

An Allegorical Reading

Little Nell as comforter by George Cattermole. "Mr. Daniel Quilp, having entered unseen, was looking on with his accustomed grin." — Chapter 9. Right: "A Very Aged, Ghostly Place" — chapter 46. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

How should we understand Dickens then in the twenty-first century? One way of reading this novel in particular, picking up from Bowen’s idea would be as a pure allegory of Innocence (pre-industrial) impersonated by Little Nell and Evil (industrial money dependence) embodied in the physically repelling Quilp. If we take this approach, then Quilp becomes the ugly face of our money-dependent world, and he is ugly not because he is a dwarf, but because money dependence distorts, belittles, and deforms. The very embodiment of Innocence, Little Nell is helpless, obedient, and ultimately doomed to perish as innocence always does, losing the battle with the industrial world. Although people can remain innocent up to a point, they lose their innocence sooner or later, become more or less like the others. Nell, innocence itself, cannot do so and has to succumb to her fate, which is also locked in the play of words on her name: Nell — knell.

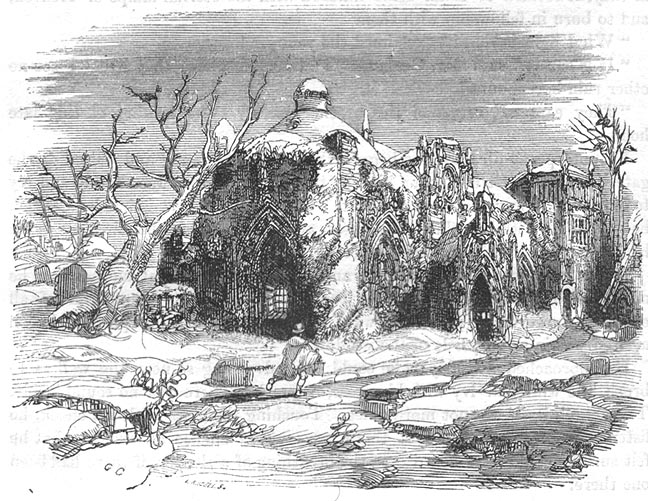

Resting Among The Tombs by George Cattermole. — Chapter 53. Right: "The Journey's end" — chapter 70. The picture illustrates "Kit darted off, the birdcage in his hand, towards the spot where the light was shining in the parsonage." [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Another way of reading this story could be as a Victorian fairy tale in which the microcosm of the Old Curiosity Shop shatters, letting loose its characters into the big wide world where they continue acting, interacting, and reacting one to the other until they eventually consume their energy in their predestined demise, which coincides with the destruction of their microcosm — The Old Curiosity Shop. As Chesterton suggested, they are curiosities from the shop itself (xv), antique primordial forces released into the world populated by normal creatures like Dick Swiveller and the Marchioness, who Dickens places there to establish a link to the normal world and that of the Old Curiosity Shop. In this reading, Little Nell is not just surrounded by grotesque curiosities; she is very much one herself. In other words, she is definitely not a Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz but instead more like the Brave Tin Soldier, who, once released into the broad world can only sadly observe the innumerable misfortunes on his way to his own end.

Very much in the same vein of thought, Little Nell, who once released from the shop in search of a refuge from the clutches of Quilp, embarks on a journey to a supposed paradise regained. However, while she does regain peace and quiet, her road is beset with death leading only to her own death making happiness only available in another state, a spiritual one.

De-territorializing and Re-territorializing Innocence: Innocence Uninterrupted

Her death-bed scene deterritorializes Innocence, which is no longer to be found in the fictional world of the novel. Dickens represents our world deprived of innocence by Nell’s death, but innocence is, at the same time, being reterritorialized by her entering another life supposedly much better than the one we know on Earth:

She was dead. No sleep so beautiful and calm, so free from trace of pain, so fair to look upon. She seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God, and waiting for the breath of life; not one who had lived and suffered death. [524; italics mine]

The Soul of Littlr Nell ascending to heaven by George Cattermole.

The contrast of life and death reteritorrializes innocence. The natural end of life as we know it is death, so her being Innocence itself cannot be associated with a horrible death, the one reserved for Quilp — her opposite and the impersonation of Evil. The passing from life on Earth to life in the realm of God is likened to a sleep from which she is about to awake. A similar idea was used in the movie Avatar (2009) in which the main character Jake Sully, a paraplegic former marine literally transcends from miserable and rather limited human existence on Earth into the fantastic life in the body of a Na’vi humanoid by waking up.

Nell’s expressed desire to be put near objects after her death that have loved light, pointing at all times to the sky, associates innocence with the divine celestial realms of God towards which innocence, embodied by Nell, has always aspired during its short existence in Industrial England. This also accentuates the fact that innocence must be very transient in our post-industrial world of late or corporate capitalism, and its reterritorialization is established after a very short ephemeral existence. J.M. Barrie, the author of Peter Pan (1911) was to say that two “is the beginning of the end”, referring to Wendy and the fact that pure unadulterated innocence can have a very short life-span, after which it can only be modified by a number of social factors until it is inevitably lost and gone. The attempt, therefore, to sustain it longer in its pure intact state could be possible in the earlier stages of industrial society, which accounts for the fact that it is reterritorialized in afterlife after almost 14 years of Earth existence. It is not by chance that Dickens chose the age of 13 for Nell Trent, since 14 was considered a marrying age in Victorian England. In the novel she could have been married to Dick Swiveller or even Quilp, and innocence as we know it in her would have ended then and there. Quilp would not have had to die, either in that case as his energy would not have been exhausted in neutralizing innocence. Dickens, however, was after a different solution to the money problem, in which it was innocence that had to be spared by its transposition into a different existence with God, not Nell, who in the novel is nothing but its avatar. It is this avatar of innocence that we are observing in her death-bed scene in which all is very calm and peaceful. The overall effect of the novel, then, reads as Innocence Uninterrupted. This in itself was a great consolation for many families in which child death had occurred, a phenomenon much more typical in that age than it is nowadays.

The juxtaposition of peaceful Nell lying in her death-bed and the frantic movements of her bird in its cage emphasizes the contrast of Innocence Transcended and petty miserable life still continuing:

She was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Nell was dead. Her little bird — a poor slight thing the pressure of a finger would have crushed — was stirring nimbly in its cage; and the strong heart of its child-mistress was mute and motionless for ever. [524]

These lines from the description of Nell’s bed-scene have given rise to an outcry that this is Dickens at his worst. He is commonly regarded as the single classic of the magnitude of Shakespeare but who has passages of brilliance alternating with badly structured, maudlin, downright mediocre writing by Victorian and modern standards. It has to be admitted that critics, such as h and Huxley, condemned Dickens as overly sentimental because the very first lines of this passage catalogue Nell's sanctifying qualities, thus elevating her to the pedestal of a saint. This listing of attributes, however, is only natural if we look at the novel in the light of an ode to Innocence Preserved or a panegyric alluding to Mary Hogarth, Dickens’s beloved sister-in-law who died in his arms in 1837. It is a well-known fact, stated by Dickens himself, that he “was breaking his heart over this novel”, as well as the fact the he would have lapses of didactism and sentimentalism in any piece of writing he would produce, especially, in his earlier works.

Other Interpretations: Little Nell Deconstructed Further

Much more attention, in my opinion, should be paid to the stark contrast of the frantic activity of the encaged bird with the complete peace and quiet reigning in the room where everyone but the deranged grandfather observes a spell of silence. Why would Dickens have had to put the bird in the same room with Nell lying in her death-bed? Another example of very bad writing? This, as anything else, can only be a subject of interpretation if we take it this way. This passage then illustrates the irrelevance and meaninglessness of life on Earth experienced by other creatures against the passage of Nell into another state of being. According to this reading, Nell's death-scene successfully shows the prevalence of insignificant life on Earth over the stately notion of innocence ascending to a better world or a better life. A different reading would reveal the irony of life as we know it, where a saintly child like Nell Trent is survived by a tiny bird, which could easily be killed by anyone’s just pressing a finger on it. From this, it only follows that life carries on regardless and objectively nothing has any meaning at all to the best of our knowledge no matter what qualifications or interpretations we would give it. It is, in fact, the wonder of life and the wonder of death that are being contemplated here and no matter how we would interpret these lines, they go to show that Dickens, even when considered by many to be at his worst, was writing in a manner that challenged the common literary perceptions of his times and still challenges the literary norms of today as much as they exist in postmodernity.

Conclusion

The proposed interpretations of Nell’s character and her death-bed scene do not, by any means, exhaust all the possibilities of deconstructing the analyzed passage. They, together with the ones given by Wilde, Huxley, and others, only enrich the scope of possible understandings of this passage and will hopefully open room for yet further analyses.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop [1841]. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1907.

Huxley, Aldous. Vulgarity in Literature (1930).

Bowen John. Dickens and the Children of Empire. New York: Palgrave Publishers, 2000.

Chesterton, G.K. “Introduction” in The Old Curiosity Shop [1841]. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1907.

Created 29 June 2011

Last modified 15 August 2025 (headnote amended)