Lillian Nayder. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornell U. P., Dec. 2001. Pp. xiv + 221. £23.50 ISBN 0-8014-3925-6

Chapter 1: Professional Writers and Hired Hands:

Household Words and the

Victorian Publishing Business, pp. 15-34.

Chapter 1: Professional Writers and Hired Hands:

Household Words and the

Victorian Publishing Business, pp. 15-34.

Chapter 2: Collins Joins Dickens's Management Team: "The Wreck of the Golden Mary," pp.

35-59.

Chapter 3: The Cannibal, the Nurse, and the Cook: Variants of The Frozen Deep," pp. 60-99.

Chapter 4: Class Consciousness and

the Indian Mutiny: The Collaborative Fiction of 1857, pp. 100-128.

Chapter 5: "No

Thoroughfare": The Problem of Illegitimacy, pp. 129-162.

Chapter 6: Crimes of the

Empire, Contagion of the East: The Moonstone and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, pp. 163-197.

Conclusion: "This Unclean Spirit of Imitation": Dickens and the "Problem" of Collins's

Influence, pp. 198-202.

Andrew Gasson, "A Contemporary Victorian Writer: Wilkie Collins" and Andrew Gasson and Alan S. Watts, "Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens: Collaborators." The Dickens Magazine, Part B, Series 1, Issue 5. Haslemere, Surrey, 2001. Pp. 29.

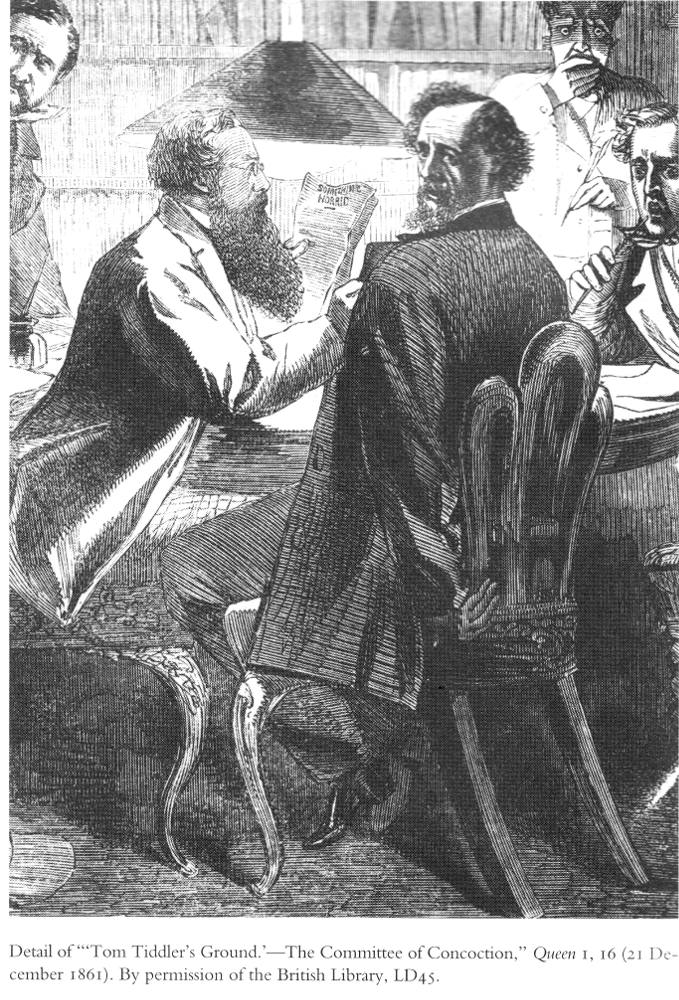

Oddly enough, my review copy of Lillian Nayder's analysis of the professional collaborations of Collins and Dickens, and their influence on each other, arrived at the same time as my overdue copy of The Dickens Magazine, Part B, Series 1, Issue 5 (the second-to-the-last in the series on Great Expectations). Serrendipidously, the focal point of this issue of the periodical, Dickens as journalist and collaborator with Collins, overlapped with the book. Gasson, Chair of the Wilkie Collins Society, presents us with the familiar Collins, the creator of the Detective Novel and the Sensation Novel, and the author of such Victorian best-sellers as The Woman in White and Armadale. In "Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens: Collaborators," Andrew Gasson teams up with Alan Watts, editor of The Dickens Magazine and long-time member of The Dickens Fellowship in London, to enumerate and briefly describe the eight Christmas stories that Collins and Dickens wrote together, while failing to note the contributions of the other members of Dickens's "stable of writers": Augustus Sala, Elizabeth Gaskell, Adelaide Anne Procter, Eliza Lynn Linton, Harriet Parr, and Percy Fitzgerald. Focussing on 1867's No Thoroughfare, they leave out The Frozen Deep entirely. Nor do they ever hint at there having been trouble in the mid-Victorian periodical writers' paradise of the office of Household Words at 26 Wellington Street, off the Strand: "Their association became one in which work and play were inextricably bound together" (18).

In fact, Nayder contends that, after Dickens's death in 1870, Collins falsified the nature of their relationship as collaborators by furnishing publisher Edward Chapman "with an image of equity and partnership that was rarely, if ever, achieved" (202) so that the younger writer's contributions to No Thoroughfare would not be excised from future editions of Christmas Stories. His concern was not so much the integrity of text, contends Nayder, as the security of his own position in the annals of English literature, a position that The Moonstone and No Name have irrevocably secured. "Yet we can only realize his significance to that history in the fullest sense by questioning images of equity between himself and Dickens, particularly those the collaborators themselves provided, and examining the editorial practices — both Victorian and modern — that make certain writers disappear" (Nayder 202). She has in mind those other, female members of the company in which Collins and Dickens wrote the Christmas Stories, as we see in Margaret Lane's introduction to The Oxford Illustrated Dickens in the 1956 edition, which notes the influence of Collins on the elaborate plotting of these pieces, but which mentions none of the others.

When the pair first met in April 1852, Dickens was forty years of age, and already a Victorian institution. Collins, twelve years his junior, was a virtual nobody in the literary sense, although his father had been a noted painter. When twenty-seven-year-old Collins began writing for Charles Dickens's weekly magazine Household Words, Dickens owned a half-share in the magazine, received an annual salary of five hundred pounds, and had average annual income of anywhere from £1,163 to £1,652 from his work on the magazine. Collins was initially paid by the column, although in September 1856 his salary rose to five guineas a week when he finally became a staff writer.

As both the editor and part-owner of a large circulation weekly magazine Dickens grew increasingly reluctant to publish any narrative such as Charles Reade's Sensation Novel Hard Cash (1863) that had the potential to offend his broad readership. Conversely, as he won public acknowledgement Collins more aggressively challenged conventional thinking with his treatments of women' s rights, the conditions of the working class, the rights of conquered races, and the taint of illegitimacy. In Unequal Partners Nayder graphs a progressively difficult partnership from Collins's initial hero-worship of The Inimitable, for whom he was content to be a mere ampersand, through a more equitable division of labours which still excluded control of the total artistic vision of a work, to Collins's parting company with Dickens in 1862 after eight Christmas Stories, The Frozen Deep in its initial form, and "The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices." When Collins returned to All the Year Round to work on "No Thoroughfare," he was an established author prepared to challenge the authority of the journal's "Conductor" by radically altering the story for the stage. Finally, Nayder provides a refreshing and challenging reading of The Moonstone and The Mystery of Edwin Drood as diametrically opposed in matters of gender and race.

Sometimes the application of twentieth-century critical perspectives to pre-twentieth-century texts results in readings that are totally alien to the original publication context — de-historicized, if you will. In contrast, Lillian Nayder's application of post-colonial and feminist lenses to the pages of Dickens's and Collins's collaborations, which is consistently New Historicist in orientation, offers fresh and highly perceptive insights into these often forgotten stepchildren among Dickens's literary progeny. Using their correspondence, Nayder reveals their very different attitudes towards class relations, female exploitation and autonomy, imperialism and its subalterns, all nicely foregrounded in her assessment of The Wreck of the Golden Mary, The Frozen Deep, The Perils of Certain English Prisoners, and No Thoroughfare, all of which she asserts reflect Dickens's response to those contemporary challenges to British imperialism, the loss of the Franklin Expedition in the Arctic and the Sepoy Mutiny in India. Even so slight a piece as "The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices," which features Dickens as "Francis Goodchild" and Collins as "Thomas Idle," reflects Dickens's anxieties about class conflict and about his mastery of Collins, shown again when the two become Richard Wardour and Frank Aldersley in The Frozen Deep. By the 1850s increasingly more conservative on social questions, Dickens endorsed in the pages of his weekly journals a patriarchal-imperialist stance, viewing native uprisings and the movement of women outside the domestic sphere as unnatural and even pernicious. As Nayder convincingly argues through careful readings of each of their contributions to eleven collaborative works spanning fourteen years (1854-1867), Collins, while appearing to be subservient to the Maestro's agenda, was in fact often subverting it. In these annual "concoctions for Christmas," Dickens laid out the scenarios for his writing team, but always reserved the central and authoritative role as determiner of plot, setting, and character for himself. For example, in The Wreck of the Golden Mary Dickens assumed the captain's narrative and assigned that for the first mate (whom he appropriately named "John Steadiman") to his acolyte, Collins. While Dickens uses his portions of the novella to expose the inherent dangers of female emancipation and "to displace the problem of labor unrest in the merchant marine" (54), Collins employs his portions of the narrative to justify the smoldering resentment of subordinates, causing the surviving sailors to desert and refuse to return to their home port and replacing Dickens's Ravender with Steadiman as commander.

The textual history of The Frozen Deep, its its many iterations from 1855 through 1874, even more clearly dramatizes the rocky creative relationship between the two writers. While in his re-drafting of the script Dickens reveals his skepticism about "second sight" and perhaps even a distaste for the Highlander Nurse Ester as a racial "other" (possibly a reflection of his estranged wife's Scottish origins), as well as his utter devotion to the conception of Sir John Franklin and his party as upholders of imperial and manly virtues, Collins credits Nurse Esther's clairvoyance while focusing on gender inequities and tensions between officers and crew. Just as there are two fundamentally opposed versions of The Frozen Deep, there are two equally antithetical texts of "No Thoroughfare," that directed by Dickens for the pages of the Extra Christmas Number of All the Year Round (12 December 1867) and that subsequently adapted by Collins for the stage of the New Adelphi, where Dickens's swarthy and perfidious Swiss "savage" Obenreizer became a sympathetic figure and even a tragic hero enacted by Charles Fechter. This second text Dickens was powerless to control since he was in America on his second reading tour. Dickens's resentment of Collins's success over the previous five years may be reflected in Obenreizer's attempted murder of Vendale; certainly the success of the play must have underscored for Dickens the fact that his former protege was now his own man.

Finally, Nayder juxtaposes this resentment with the writers' very different social convictions in her consideration of The Moonstone (serialised in All the Year Round in 1868) and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (serialised in monthly parts in 1870). She construes the former novel as a postcolonial denunciation of British treatment of India and China (seeing Blake's theft of the diamond while under the influence of opium as a violation of the somewhat Eastern-looking Rachel Verinder) by setting how contemporary readers would have viewed opium consumption within the New Historicist context of Britain's opium wars, setting the heroic Brahmins and duplicitous Godfrey Ablewhite (an exponent of cultural destruction through Christianizing the heathen, and an expropriator like "The Honourable John" Herncastle of others' property) against a sordid backdrop of Victorian commerce, colonialism, and militarism.

Nayder does not deal with the implications of both Collins's and Dickens's leading a double life during this period, but sees Dickens in terms of the jealous uncle, John Jasper, and the gifted nephew, Edwin Drood, although in reality Dickens was the imperialist and Collins the opium-addict. She convincingly portrays Jasper as infected or contaminated by Orientalism, suggesting his scarf connects him to the Thug cult of the Indian goddess Kali. Throughout what we have of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, theorizes Nayder, Dickens implies that the English, masters of empire, are already reverting to the physical and moral complexion of the subject races, just as Ablewhite adopts a swarthy disguise in order to escape undetected with the purloined diamond to Amsterdam, which he intends to convert a cultural and religious icon into a saleable commodity and, ultimately, hard cash to support his deviant lifestyle. That The Mystery of Edwin Drood is a response to Collins's style and concerns does not, argues Nayder, reveal that Dickens's creative powers were diminished by his association with Collins; rather, the older writer learned from the younger, and expanded his universe far beyond the moral and social constraints of The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist. Thus, Dickens in his last creative effort may be seen to be transcending earlier and simpler social constructions which Collins in his marginal comments to Forster's Life of Charles Dickens derided as "this wretched English claptrap" (Pall Mall Gazette, 20 January 1890, page 3).

Related Material

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Gasson, Andrew. "A Contemporary Victorian Writer: Wilkie Collins." The Dickens Magazine, Part B, Series 1, Issue 5. Haslemere, Surrey, 2001.

Klimaszewski, Melisa. Collaborative Dickens: Authorship and Victorian Periodicals. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Watts, Alan S. "Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens: Collaborators." The Dickens Magazine, Part B, Series 1, Issue 5. Haslemere, Surrey, 2001.

Created 24 June 2007

Last modified 28 January 2026