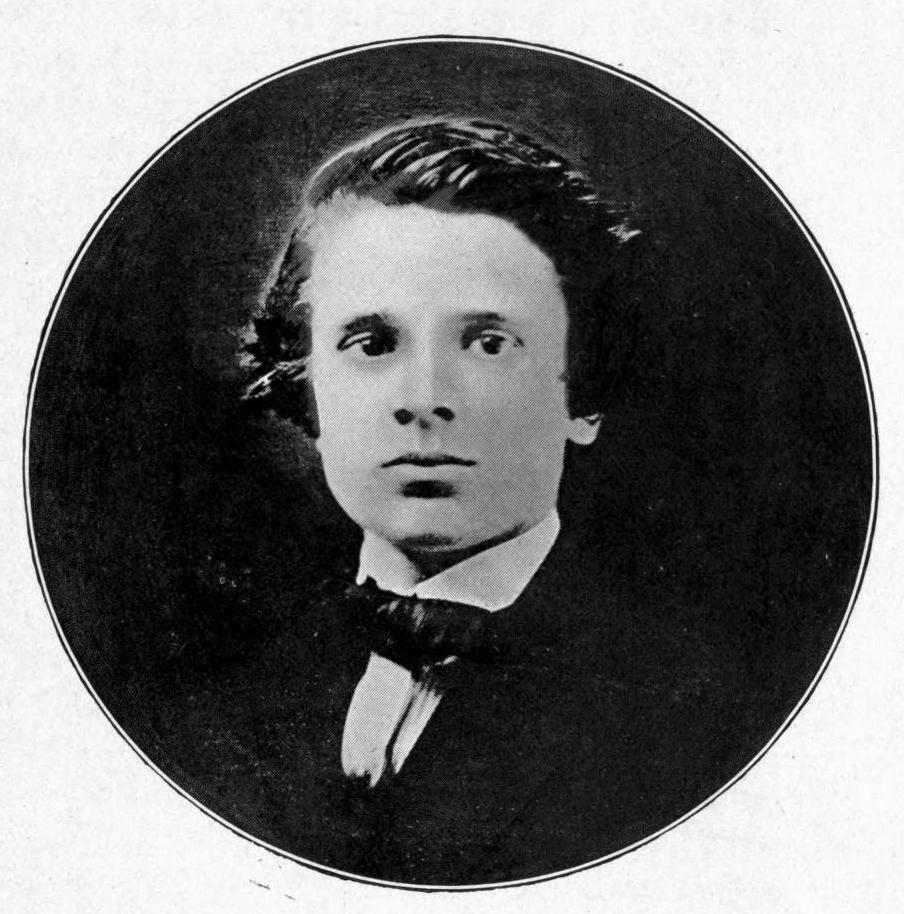

William Black at 16, from a photograph.

he novelist William Black was born into the family of a small businessman, who himself came from farming stock, in the Trongate, Glasgow, in 1841. After a very piecemeal education, independent reading, and a great deal of exposure to the beauty of the Scottish countryside, he went on to study art in his hometown. As he put it self-deprecatingly himself, "the chiefest of my ambitions was to became a landscape painter, and I labored away for a year or two at the Government School of Art, and presented my friends with the most horrible abominations in watercolor and oil. As an artist I was a complete failure, and so was qualified for becoming in after life - for a time — an art critic (qtd. in "William Black").

Realising that he was unsuited to a career as a painter, Black then veered into journalism, coming down to London in 1864. Here, his friendship with fellow-Glaswegian Robert Buchanan, then himself in the periodicals world, brought him useful contacts. He was associated with various newspapers, becoming adept at writing leaders. He even went out in 1866 to report on the Franco-Prussian War as a special correspondent for the radical Morning Star. "My subsequest connection with journalism may be briefly summed up." he wrote. "I was for about a year editor of The London Review, and afterwards. for a short period, of The Examiner, and in 1870 became assistant editor of the Daily News" (qtd. in "William Black"). But he had already found his true metiér. He had published his first novel, James Merle, An Autobiography, in the very year he arrived in the capital, and was soon having considerable success with the novels that followed it, especially his third novel In Silk Attire (1869) and his seventh, A Daughter of Heth (1871), which ran to many editions. Within three years of the latter's publication, says another of his friends, his earliest biographer, Thomas Wemyss Reid, "William Black's name was bracketed with those of the greatest novelists of the day" (25). As a result, from 1875 Black was able to devote himself entirely to novel-writing.

Left to right: (a) William Black as A Knight of the Seventeenth Century, by Scottish artist John Pettie in 1877 (Glasgow Life Museums, via Art UK on the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND)). (b) Cover of White Heather (1885), decorated with gilt thistles at each corner, from a copy in the Internet Archive. (c) Black as as one of the caricaturist Spy's "men of the day" in Vanity Fair, 1891.

Discussing his success, and (rather amusingly) taking a sly shot at the rise of the New Woman, one critic wrote later in the Literary News,

Black's specialities were scenery and natural, lovable girls. Today when outdoor life has become a creed and when railroads and steamships have enabled almost all cultured readers to see for themselves the scenery of England and Scotland, which Black painted in glowing word-pictures, there cannot be the same thrill of the new and the unkown that his first readers responded to with such acclamation. But the thirty years that have passed since novelists began to describe nature, and during which readers have gone about and verified their pictures, have not increased the number of natural, lovable, loving girls, and it is a melancholy truth that these must be sought for and are found more and more in works of imagination only. Black’s novels are a gallery of portraits of charming women. [16]

By all accounts, Black remained modest, genial and sociable, and was quite unchanged by his success. He had two great sorrows in his personal life. His first wife, Augusta (née Wenzel), who was German, died in 1866 just over a year after their marriage. His widowed mother came down to Clapham, where he was now living, to help take care of the couple's baby son, Martin. But then the little boy, who was barely five years old and was to be his only child, died in 1871. These blows hit him hard. However, he remarried in 1874, his second wife being Eva Simpson, daughter of fellow journalist Wharton Simpson. Black's generally high spirits had helped him come to term with his losses, and this marriage was a long and happy one.

In 1878, the couple left their home in Camberwell Grove in London, and settled in some style in Brighton, where their hospitality made them an attractive destination for their friends. Here on the south coast, but still within easy reach of London, Black could indulge in his favourite outdoor hobby — yachting. He also loved to walk for miles, over the downs inland, or, "best-loved of all, by the cliff road to Rottingdean" (Reid 232). After a long and difficult illness, characterised by the critic John Sutherland as a number of "obscure nervous ailmements" (65), he died in 1898 and was buried near the church door of St Margaret's, Rottingdean, close to the grave of Edward Burne-Jones. One of those who accompanied the burial procession was the marine artist Colin Hunter, a friend of Black's since their early days in Glasgow; Rudyard Kipling came to pay his respects too, despite an earlier disagreement with him over the American Copyright Act — typically, Black had been too generous, Kipling felt, about Harpers' having issued his works before they were protected by law (see Reid 394).

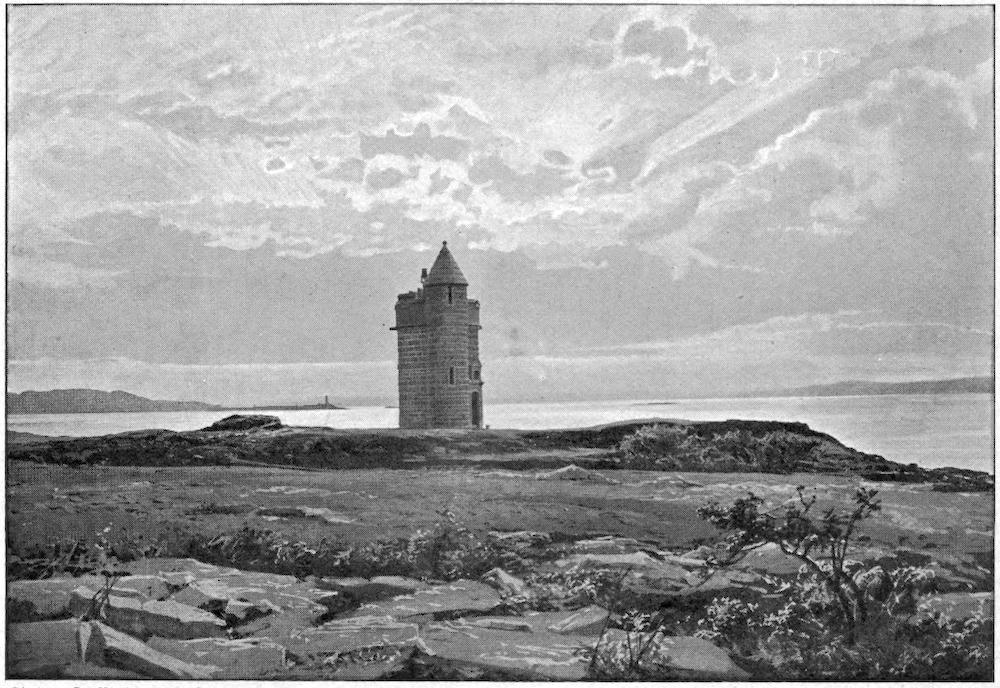

Left: St Margaret's Church, Rottingdean, Black's last resting-place (to the left of the church door)[Click on this image for more information about it.]. Right: The William Black Memorial beacon, designed by the Scottish architect William Leiper, standing on Duart Point, Mull, in the Hebrides (Reid, facing p. 394).

By the time of his death, however, "Black had somewhat lost his hold upon the present generation," writes the Literary News critic ("William Black," 16). Although this critic's counterpart in Book Notes starts his evaluation of Black with some praise, he helps to explain why his reputation had faded, noting the unevenness of his work and ending with rather a damning comment: "An industrious writer, he left a long line of stories of varying interest and quality. His touch was light, his fancy graceful, his sentiment fresh. He did not deal with problems; nor did he touch the deeper psychology of life" (35). After all, the novelist who had been considered one of the best of the age has remained trapped in it, and is perhaps best known now for having given his name to the William Black memorial beacon, designed by the Scottish architect William Leiper, standing on the Hebridean island of Mull, in the scenery that provided the setting for one of his most popular novels, A Princess of Thule (1874).

Bibliography

Black, William. White Heather. London: Sampson Low, 1890. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Library. Web. 18 January 2025.

Garnett, Richard, and S. R. J. Baudry. "Black, William (1841–1898), journalist and novelist." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 18 January 2025.

"Literary Pickups" (by "The Bookworm"). Book Notes: A Monthly Literary Magazine and Review of New Books. New Series, Vol.2 (January 1899): 34-39. Google Books. Free ebook.

Reid, Thomas Wemyss. William Black, Novelist. London: Cassell, 1902. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 18 January 2025.

Sutherland, John. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. Pbk ed. London: Longman, 1990.

The Treasury of Modern Biography: A Gallery of Literary Sketches of Eminent Men and Women of the Nineteenth Century. Compiled and selected by Robert Cochrane. Edinburgh: W.P. Nimmo, Hay, & Mitchell, 1889. Google Books. Free ebook.

"William Black." The Literary News: A Monthly Journal of Current Literature, Vol. 20 (January 1899): 16. Google Books. Free ebook.

Created 18 January 2025

Last modified 24 January 2025