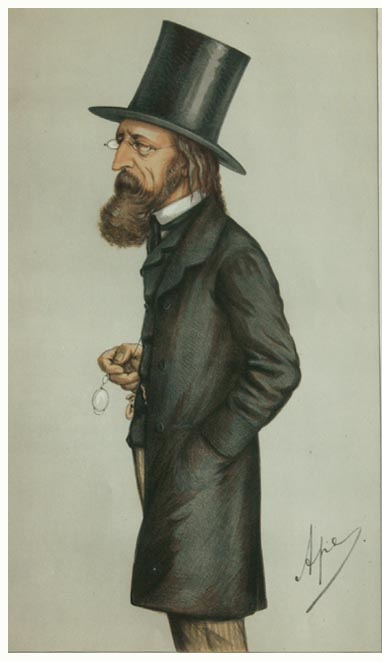

The Poet Laureate

Ape

22 July 1871

Vanity Fair

"Men of the Day No. 28" [Alfred Tennyson]

"No. 142" appears at lower left.

Other Vanity Fair Caricatures

Photograph and text 2006 by George P. Landow.

[Victorian Web Home —> Alfred Lord Tennyson —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Vanity Fair —> Next]

The Poet Laureate

Ape

22 July 1871

Vanity Fair

"Men of the Day No. 28" [Alfred Tennyson]

"No. 142" appears at lower left.

Other Vanity Fair Caricatures

Photograph and text 2006 by George P. Landow.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

THERE has arisen of late with regard to the Poet Laureate that reaction which seems fatally destined to overtake all men who are famous in their own lifetime; and it has become a fashion to doubt his genius and to depreciate his works. In spite of all, however, he remains unquestionably what the public voice has long pronounced him, the first poet of our day, and he will endure as one of the first that all time has produced. The greatest living master, for certain purposes, of the English language, he has revealed to the most refined all its unsuspected treasures of richness and delicacy, and has yet poured them out in such simple and sober channels that his songs go straight to the hearts of the most homely. The mere mention of his name awakens in every Englishman an echo of sweet sounds gently rippled into flowing verse, which lies about the chambers of the memory like the low hum of a summer afternoon, and which harmonises as nothing else can with the spirit of a sentimental and peaceful generation.

Nevertheless, Mr. Tennyson is perhaps the poet who has done the most to teach us that there is after all no use in poetry. He lacks the blind driving passion and the fierce faith of the very greatest poets. The beautiful and the true seem to act upon him, but never to enter into him. He seeks to be both teacher and singer; he weaves the most delicious web of fancies; but will never let us go without pointing out that, after all, his intention is only to provide good strong homespun for the making of warm raiment. "Oh! teach the orphan-boy to read, or teach the orphan-girl to sew" is the conclusion to which he continually points as sufficient and satisfying for men and poets here below, and to this he brings us ever from the highest flights of fancy with something of the sensation of a fall and a bruise. "The glorious Devil, large in heart and brain, that did love Beauty only," appears to him a shocking example altogether unlovely, and if it can ever be said of him, as he has said of himself, that " he saw through his own soul," he must see that he is not to the full "dowered with the hate of hate, the scorn of scorn, the love of love," which he holds to be the attributes of the true poet.

Tennyson evidently feels that were he to cut loose the bonds that thus bind him to earth, he would be perhaps a greater, but certainly a more dangerous poet. He soars up continually to the great problems that lie above and about us all, but he never dares to touch them, and after doubting and wondering for a space, always turns off awed and in another direction, leaving us only confused and confounded. He is then greatest when he sinks the mystic and shows us the materialist, for there are few who more strongly feel, and none who have so tenderly displayed, a full and many-toned sympathy with this fair earth and the creatures that therein inhabit.

Last modified 25 December 2006