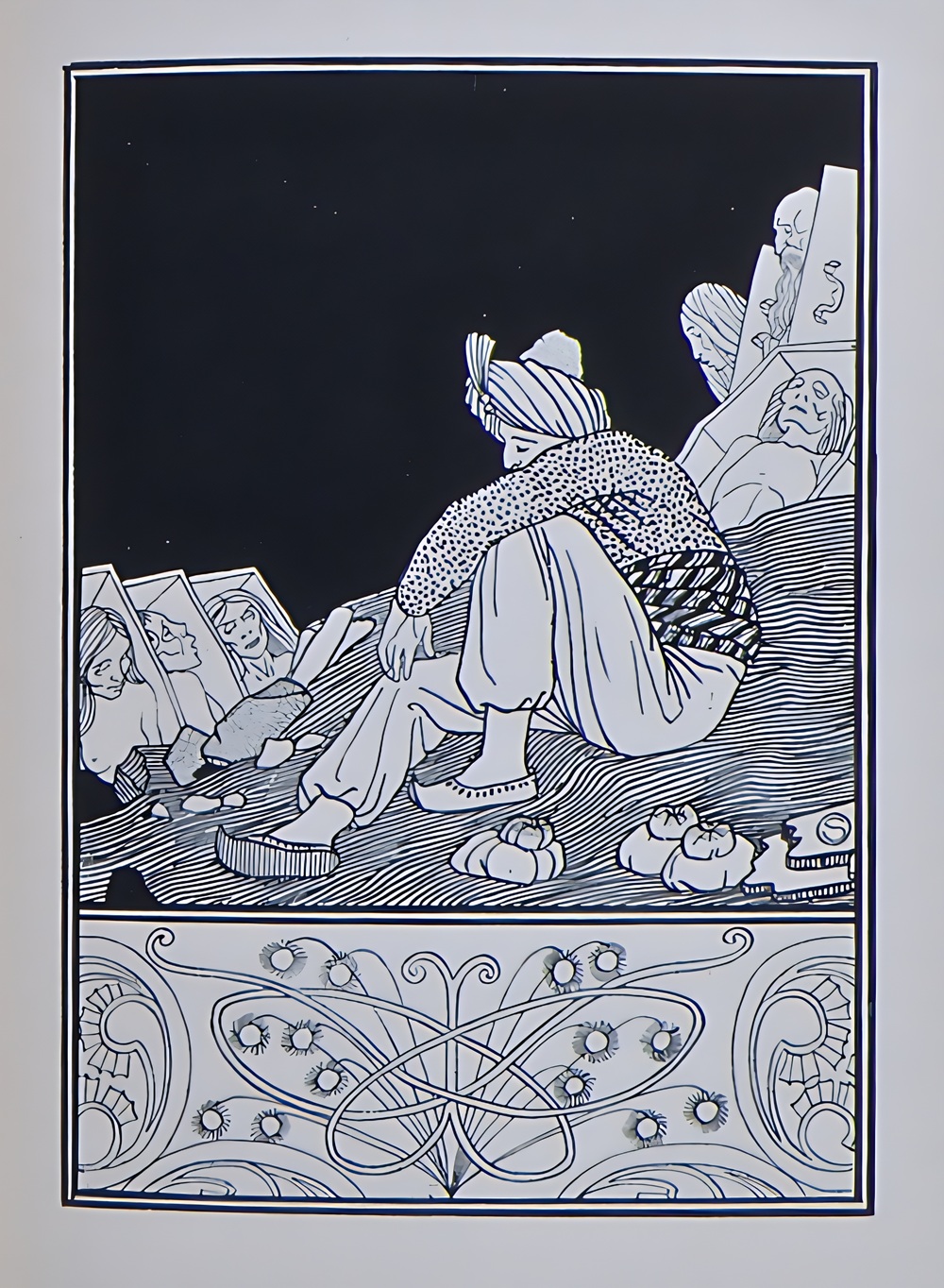

illiam Strang is best known as an engraver of free-standing prints and as a distinguished painter. Less well-known is his work as a book illustrator who practised in the 1890s and the early part of the twentieth century. In collaboration with J.B. Clarke, for instance, he illustrated two children’s books, Sinbad the Sailor (1896) and The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1895). Strang’s designs for each of these are pen and ink images photographed on glossy paper and are very much in the style of British Art Nouveau, combining a sinuous line with bold blocking of black and white and intricate detail. Though well-conceived, they closely reflect the influence of Aubrey Beardsley and demonstrate Strang’s oft-noted eclecticism as he responded to the art of old and contemporary masters.

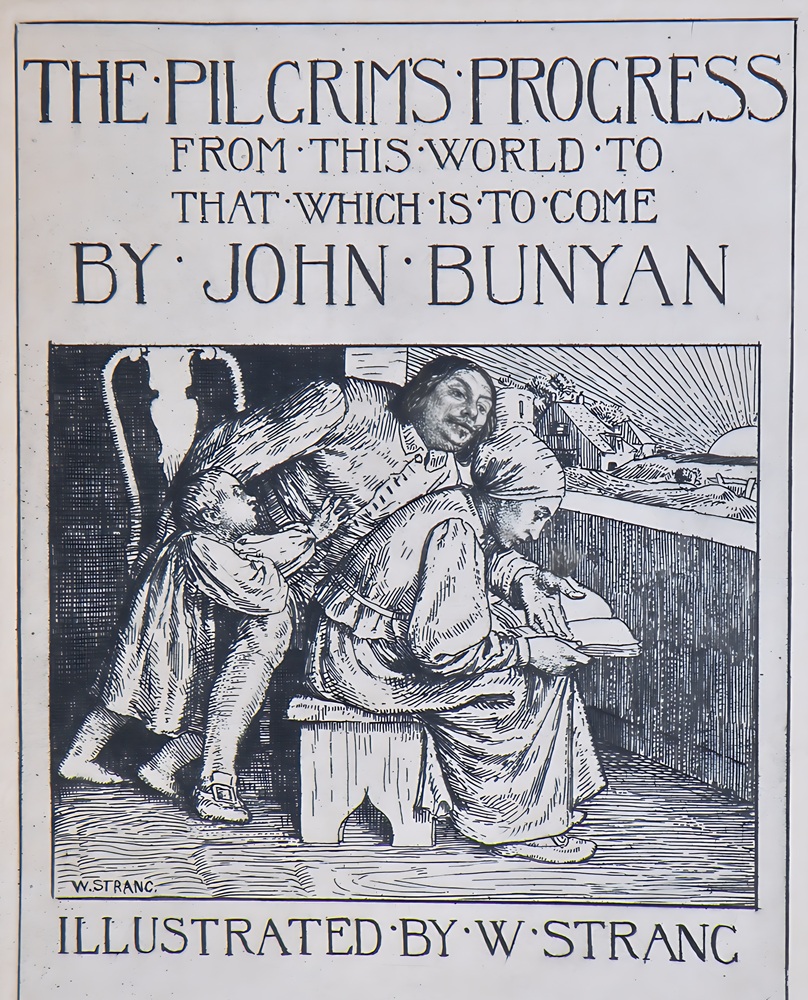

Left to right: (a) Strang in an Art Nouveau mode in The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen. (b) The artist’s title page for The Pilgrim’s Progress. (c) An illustration from Sinbad.

More distinctive, however, are his etchings for Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1904) and for the short stories of Kipling (1901). In A Series of Thirty Etchings from the Writings of Rudyard Kipling, Strang offers an intense visualization of Kipling’s tales of suffering and grotesquerie in which he presents the author’s scenes in morbid and troubling imagery. The effect, as Gordon Ray observes, is overpowering, and seems a veritable ‘chamber of horrors’ (169). Strang has generally been identified as an artist who had ‘a ‘downright passion for ugliness’ (Binyon xii) and a ‘morbid fascination’ for the ‘gruesome and ghastly’ (‘William Strang, Etcher,’ 3), and in the pages of this book, which does not reproduce any of Kipling’s text, he gives full expression to his talent for Gothic excess and Symbolist gloom. Indeed, he uses his Series to release the ever-darkening tone of his imagination. He did not consult with the author, but worked purely with the text as he provides a powerful response to the writer’s strange tales.

In so doing he satisfied his own and Kipling’s thematic and aesthetic imperatives. The particular focus is cultural dissonance: Kipling writes of the imperial white man’s encounters with an inexplicable, brutal India of strange rituals and necromancy, and Strang materializes those malign situations in dream-like designs which privilege mortality and the depredations offered to the human body. For sure, Kipling and Strang’s version of British colonialism is never less than threatening and weird, presenting a sort of alternative universe in which the colonizers struggle to make sense of an alien culture, and are frequently subject to mental and physical assault by the foreign ‘Other.’

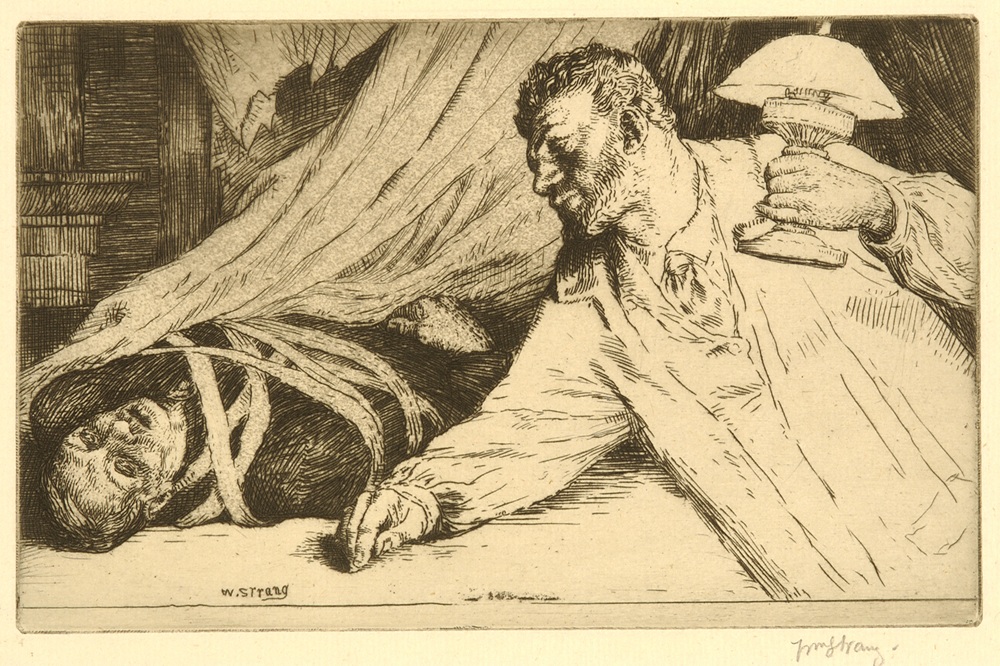

Strang focuses especially on death and physical frailty. In The Return of Imray, he depicts the body of the murdered sahib after he has crashed through the ceiling, and in The Mark of the Beast he shows the character of Fleete as an ambiguous figure with features somewhere between a man and an animal. Prostration is the key pose throughout the series, and there are several others which symbolize the artist’s morbid emphasis by concentrating on bodies in horizontal positions; if not already dead, his characters invariably look like cadavers.

Left: Strang’s The Return of Imray. Right: the same artist’s The Mark of the Beast.

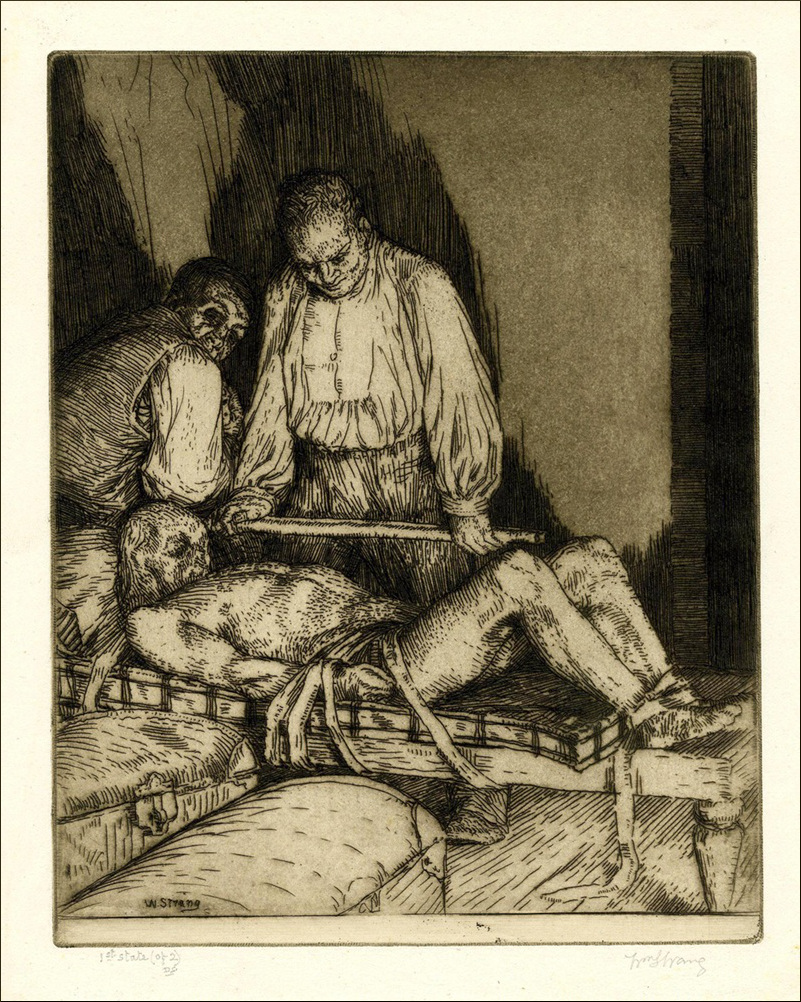

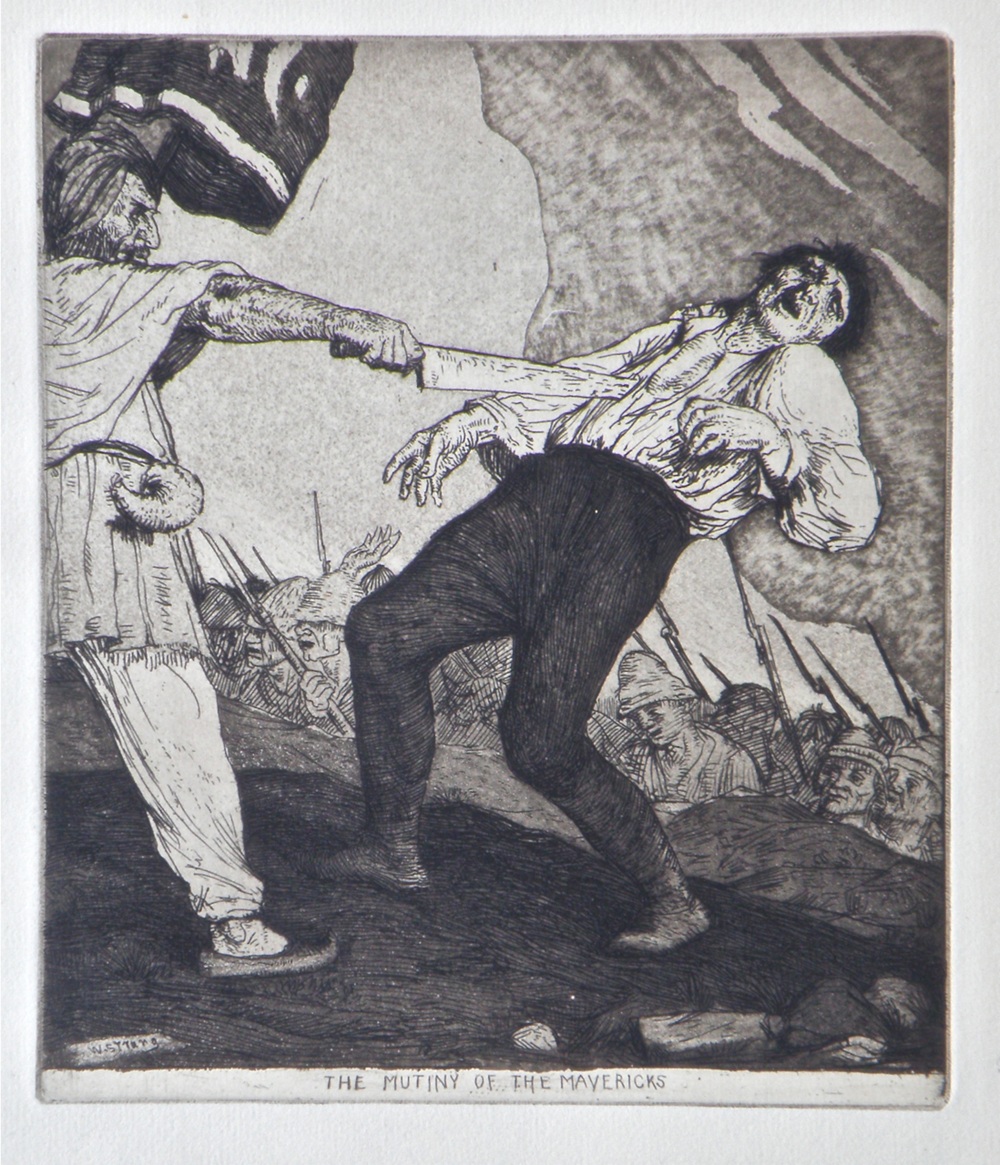

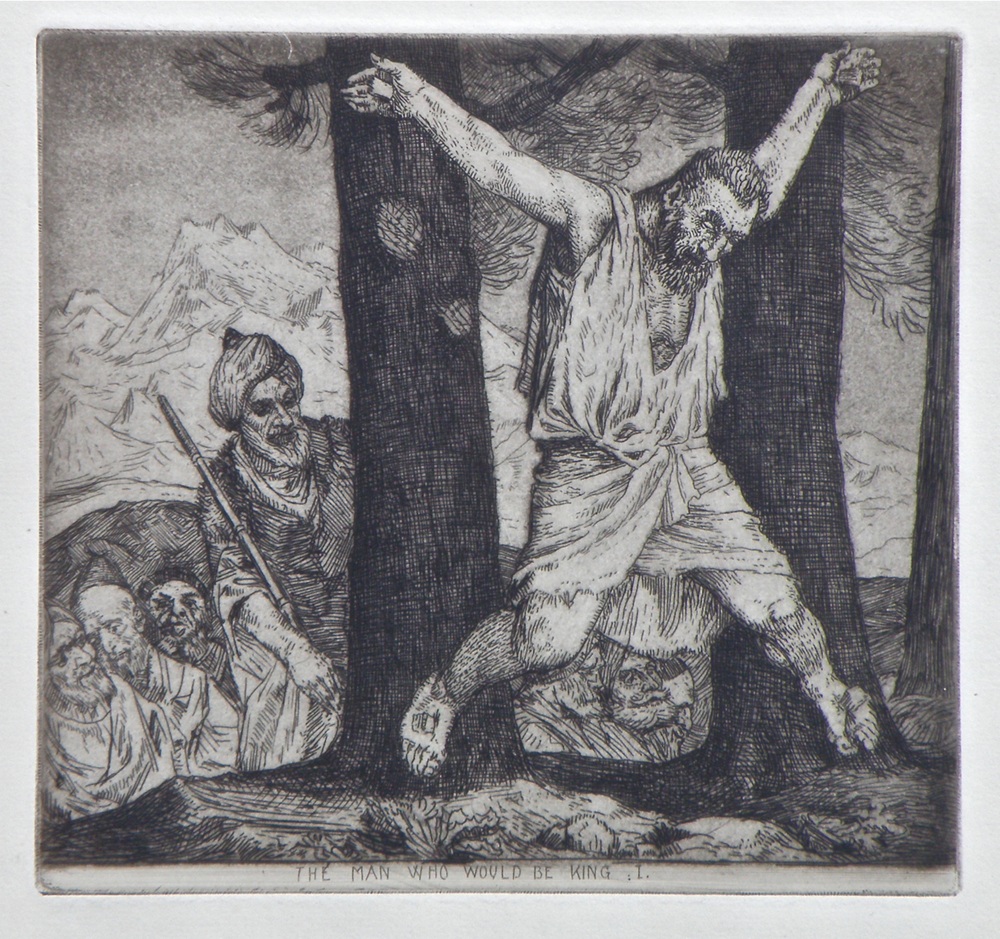

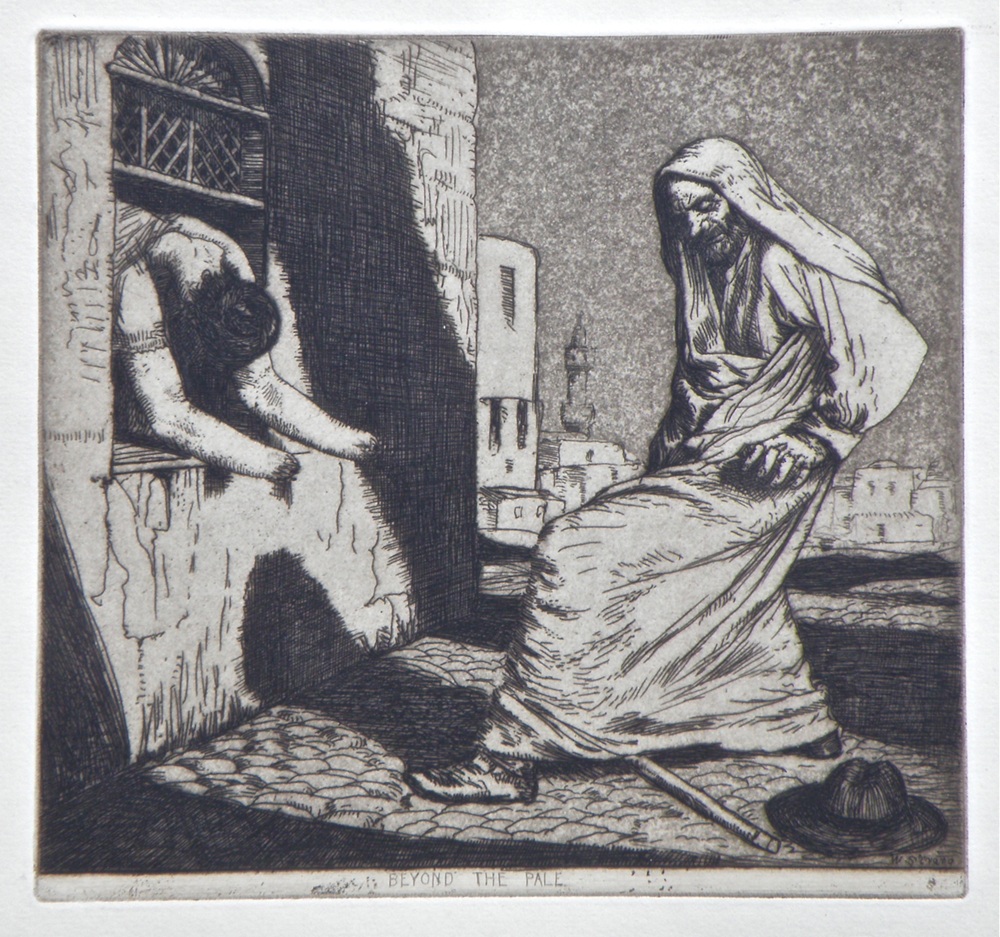

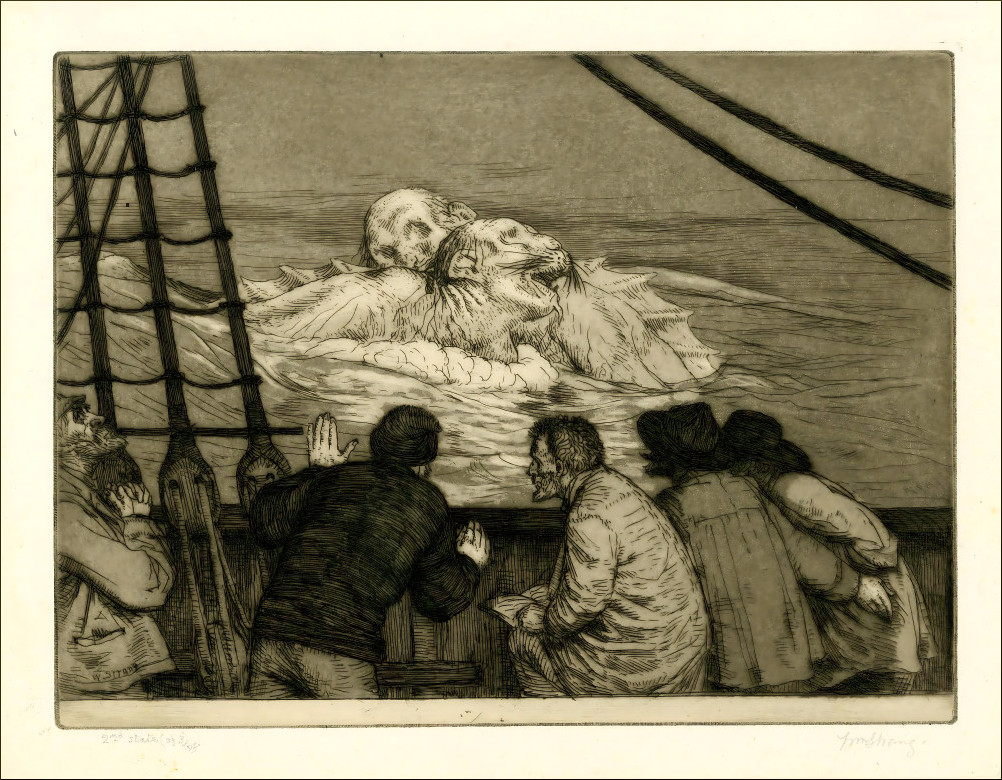

Violence and cruelty are likewise threaded through the montage, notably in the depiction of the gruesome slaying in The Mutiny of the Mavericks, in the crucifixion suffered in The Man who would be King, in the near-death of the child about to be eaten by Mugger the crocodile in The Undertakers, and in the grotesque representation of the chopped-off hands in Beyond the Pale. Strangest and most agonizing of all is the illustration of A Matter of Fact, an image of ghastly suffering as a group of hard-bitten journalists watch the death-throes of a sea-monster and the anguish of its mate.

Left to right: (a) Strang’s The Mutiny of the Mavericks. (b) The same artist’s The Man who would be King. (c) The Undertakers.

All of these works echo the uncanny art of Legros. But in these designs at least Strang is closest to the sadistic excesses of Goya, and gives vivid form to Kipling’s nightmarish exploration of the imperial experience.

Left: Strang’s Beyond the Pale. Right: A Matter of Fact.

Bibliography

Primary: Books Illustrated by Strang

The Book of Giants. London: Unicorn, 1898.

Bunyan, John. The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to that which is to come, by John Bunyan; with scenes and illustration by William Strang. New York: R. F. Fenno, 1904.

Cervantes. A series of thirty etchings by William Strang illustrating subjects from Don Quixote. London: Macmillan, 1902.

Death and the Ploughman’s Wife. London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1894.

The Doings of Death. London: Essex House, 1901. (woodcuts by Robert Brydon after William Strang)

The Earth Fiend. London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1892.

Kipling, Rudyard. A Series of Thirty Etchings by Illustrating Subjects from the Writings of Rudyard Kipling. London: Macmillan, 1901.

Lucien’s True History. Illustrated by William Strang, J. B. Clark and Aubrey Beardsley. London: privately printed, 1894.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost by John Milton: a Series of Twelve Illustrations Etched by William Strang.London: John C. Nimmo, 1896.

Sinbad the Sailor and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. Illustrated by William Strang and J.B. Clark. London: Lawrence and Buller, 1896.

The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Illustrated by William Strang and J. B. Clark. London: Lawrence and Buller, 1895.

Secondary

[Anon]. ‘William Strang, Etcher.’ Glasgow Evening Post. (3 March 1893): 557.

Binyon, Laurence. ‘Introduction.’ William Strang: Catalogue of His Etched Work. Glasgow: James Maclehose, 1906.

Ray, Gordon. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1976.

Created 4 October 2025