larkson Stanfield was a distinguished painter of marine and landscape subjects who also worked as a graphic designer. In the 1830s and 40s he contributed land and seascapes to a series of annuals and keepsakes in the form of etched versions of his paintings; he also did original illustrations, notably for Dickens’s Christmas books and Frederick Marryat’s The Pirate and the Three Cutters (1835) and Poor Jack (1840). He is perhaps best remembered for his contribution to Tennyson’s Poems – the famous ‘Moxon Tennyson’ of 1857.

Stanfield was one of eight illustrators commissioned by the publisher Moxon, who divided the work between older, established practitioners and the Pre-Raphaelites. The ‘new’ school was represented by the three founders of the Brotherhood, D.G. Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and J. E. Millais; and the ‘old school’ artists were Stanfield, Daniel Maclise, William Mulready, J. C. Horsley and Thomas Creswick.

Criticism has favoured the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, and Stanfield, in the company of the other academicians, has been described as an inferior illustrator whose work does not match up to the designs of the PRB. In the words of Martin Hardie writing in 1907, Stanfield and his immediate contemporaries were viewed as purely literal artists who ‘picked out a piece of a poem and illustrated it with the same dogged fidelity and commonplace honesty with which they painted a patch of nature’, while the Pre-Raphaelites’ approach was regarded as ‘symbolic and interpretive’ (10–11).

However, this dismissal of Stanfield’s designs – and those of his peers – is misleading; as I argue in The Moxon Tennyson (2021), such judgements are bound by late Victorian taste which championed the Pre-Raphaelites. At the time of publication, in 1857, public favour was directed more to the academicians, and the dismissal of Stanfield as a poor illustrator would have seemed strange and incongruous.

Viewed from the perspective of the twenty-first century the marine artist’s designs seem as imaginative, in their own way, as the images of the younger school: Pre-Raphaelitism demands to be interpreted in one manner, Romantic design, which is derived from the older traditions of the earlier part of the century, in another. Viewed in these terms, as a version of Romanticism, Stanfield’s designs are explicable as visual interpretations of Tennyson’s verse which illustrate the texts in the form of significant land and seascapes that act as inscriptions of meaning in the fabric of nature. In Stanfield’s work, as in all Romanticism, nature and human nature are fused into one.

Stanfield’s Interpretations of Tennyson: the Emotionalized Land and Seascape

Stanfield did six ‘drawings on wood’ for the Moxon Tennyson; with no guidance from the author or publisher, he chose his subjects. Rossetti regarded this editorial freedom with contempt, noting how ‘Stanfield will do “Break, Break”, because there is the sea in it, and “Ulysses”, too, because there are ships in it’ (Letters 97). The implication of this judgement is that Stanfield would approach the text in a formulaic way. In practice, though, he draws out several of Tennyson’s key ideas while playing to his strengths as a master of landscape and marine motifs.

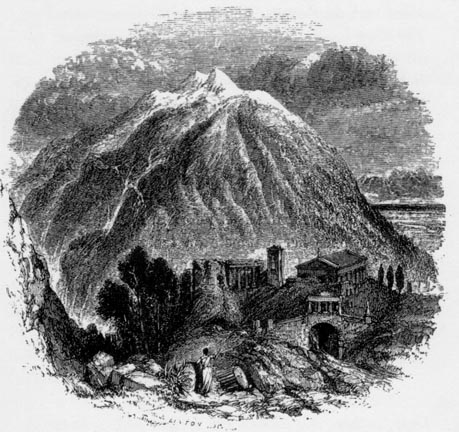

Stanfield is especially effective in finding visual equivalents to Tennyson’s writing of deep feeling. His treatment focuses on his representation of the Romantic or emotionalized land and seascape, which acts as a register, usually in complex ways, of the characters’ or narrator’s state of mind. In Oenone, he depicts the classical nymph addressing Mount Ida and confessing her ‘mournful’ (Poems 100) story as she prepares to take her own life. Stanfield manipulates scale to create a dramatic contrast between the tiny figure and the vast, sublime expanse of the landscape, which represents her previous, contented life as a ‘playmate on the hills’ (100). Ruined by her circumstances, her present condition is symbolized by the ‘fragment’ of broken masonry, visualized in tiny detail, in the foreground. Recreating Tennyson’s details, Stanfield also uses the landscape, and the character’s diminutive position within it, to comment on the vagaries of chance and the frailty of humanity. Nature continues unchanged as a vast power, but individuals are diminished, literally reduced to insignificance as they are borne down by fate.

Stanfield’s deployment of a classical landscape to accompany

a classical story in the form of Oenone.

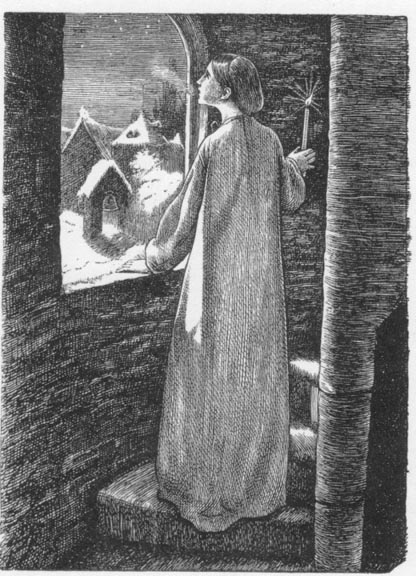

Setting is further deployed as a means of emotional expression in his design, St Agnes’ Eve. Stanfield uses the Pathetic Fallacy to materialize the saint’s anxiety as she engages with the mysteries of her ‘Heavenly Bridegroom’, which he represents in the form of the shadowy ‘convent-towers’ (310) positioned at the top of a vertiginous hillside. In contrast to Millais – who focuses on the character’s moment of doubt as she pauses on the stairwell – Stanfield’s landscape inscribes her fearfulness in an image of extremes made up of eerie contrasts of light, height, and jagged outlines. Stanfield and Millais have the same focus on psychological drama, but they approach the task of representation in very different ways.

The two illustrations for St Agnes’ Eve. Left, by Stanfield; right, by Millais.

Stanfield embodies other sets of feeling in landscapes in his strongly contrasting designs, Edwin Morris and Break, Break, Break. The first of these, ‘Edwin Morris’, is difficult to illustrate because the poem is a discussion piece, with three voices considering their romantic affairs and the behaviour of the narrator’s beloved, ‘little Letty’ (233). There is a great deal of material that could be visualized, but Stanfield chooses to represent the travellers’ setting, a landscape with ‘ruins of a castle’ (229), which also acts as an emblem of the narrator’s feelings of freedom: having ‘pardon’d (233) his former love, he now feels a sense of well-being that is symbolized by the idealized imagery of the Picturesque. Bound by the conventions of genre, Stanfield figures his design as a harmonious arrangement composed of a bridge, romanticised ruins and a deep recession of space that leads they eye into a dreamy distance, signs that stand, in this context, as a moment of calm and equilibrium.

Stanfield’s treatment of expressive landscapes. Left: Edwin Morris. Right: Break, Break, Break.

More striking is the visual inscription of Tennyson’s elegy, ‘Break, Break, Break’. The poet makes an explicit link between the tumultuous breaking of the sea and his mental turmoil as he contemplates his loss:

Break, break, break,

At the foot of thy crags, O Sea!

But the tender grace of a day that is dead

Will never come back to me. [374]

Once again, this is a type of pantheism, an intermingling of nature and human nature, and Stanfield projects the same symbolic connection. He especially captures Tennyson’s emphasis on the indifference of nature: the poet insists on the endless rhythm of the sea, unresponsive to human suffering, and Stanfield symbolizes the titanic, impersonal forces of the natural world in the form of tumbling waves of juxtaposed black and absolute white, the jagged outlines of the landscape, a vast cliff-face, and near-horizontal striations of rain. Cut by Green in a style that gives the image a tactile surface, the engraving preserves a distinct sense of tumult and rawness. It could be a real place, but its expressiveness defines it as a mental topography as well.

Tennyson, Stanfield and the Representation of Masculinity

Tennyson was centrally concerned with questions of gender, and offered a distinctive idea of what constitutes masculinity. His writing of manhood is primarily focused on the notion of male activity – insisting that manhood is expressed as a dynamic striving for achievement in which assertiveness, as opposed to female passivity, is the prime constituent. This model is embodied in ‘Ulysses’, in which the semi-domesticated adventurer contemplates breaking free and taking once again to the sea, the domain of exploration and excitement in defiance of time and ageing:

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heavenl that which we are, we are;

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. [266]

Expressed in grand rhetoric, the hero’s pronouncement offers a number of opportunities for an illustrator, and it is interesting to speculate on how others working on the Moxon Tennyson might have approached it. The Pre-Raphaelites would probably have visualized Ulysses addressing his followers, it is not difficult to imagine Holman Hunt adopting this approach. Stanfield, however, focuses on the call of the sea, visualizing a turbulent bay with boats travelling inland and outward. This is a literal illustration of the narrator’s nostalgia for the ‘scudding drifts’ where the ‘vessel puffs her sail’ (265–66). But Stanfield’s cleverly organizes the image so as to represent the poem’s theme as well, depicting the moment of assertion as Ulysses considers home-life (represented by the cityscape to the right of the composition) and freedom (the sail-borne ship heading right to left which leads the eye out of the design). The dynamic vessel’s movement connotes his decision to strive and seek, as opposed to the rowing-boat, suggesting home-life, which sails the other way. Stanfield notably endows his craft of new discovery with angular sails inflated by an invigorating wind: at once an energized image of the sea and sea-going that recalls many of his marine paintings, it is figured as an emblem of uplifting determination and vitality. Stanfield’s choice of subject is on this occasion perfectly matched to his abilities as a Romantic painter of the emotionalized sea-pieces, and here, as elsewhere, he explores the sea’s significance and its metaphorical applications. Indeed, ‘Ulysses’ enables Stanfield to work in his favoured, heroic idiom, and taken together the verbal and visual texts exemplify what one critic has described as Tennyson’s ‘masculinist’ writing.

Stanfield’s epic treatment of the story of Ulysses.

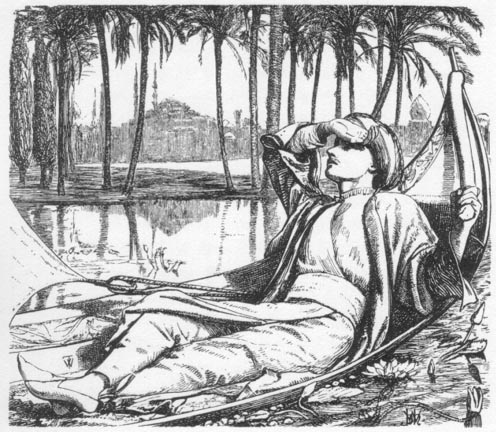

More problematic is ‘The Lotos Eaters’, in which the author reverses the situation in ‘Ulysses’, this time depicting the progress from masculine assertion to ‘slumber … more sweet than toil’ where ‘mariners … will not wander more’ (148). The poem calls for a languorous scene in the same emotional register as Holman Hunt’s depiction of the sleepy narrator in Recollections of the Arabian Nights or the sensual imagery of Mulready’s The Sea-Fairies. However, Stanfield seems unwilling or unable to respond to Tennyson’s disavowal of heroism; ignoring the soporific descriptions of ‘Slow-dropping veils’ and ‘sweet music’ (142–43), he shows the moment when Ulysses urges the sailors to land on a coast that is characterized by a rugged cliff and shows no evidence of ‘languid air’ (142). Stanfield’s design only illustrates the admonition to take courage, depicting the vessel as it moves on a turbulent sea (141); placed as a headpiece, it asserts the very values that the ensuing text will subvert and contradict.

Left: Stanfield’s The Lotos Eaters. Right: Holman Hunt’s langorous The Arabian Nights.

Stanfield’s illustrative response to Tennyson’s Poems might thus be described as complex, occasionally inconsistent, but generally ingenious and inventive. Though confined by his expertise in marine and landscape imagery, he turns that limitation to advantage, encoding Tennyson’s messages in illustrations that are free from figure drawing – except in tiny miniature – but enshrine those themes and ideas in the workings of sea and land. Usually dismissed by modern critics as being of far less interest than the Pre-Raphaelite designers, his series are as telling, in their own way, as those of the ‘up-and-coming men’. Regarded by his contemporaries as a poet, Stanfield’s visual poetry is applied to great effect in his treatment of Tennyson’s verse, and is always, as a reviewer comments in The Art Journal, ‘picturesque and truthful’ (‘Reviews’ 231).

Works Cited

Cooke, Simon. The Moxon Tennyson: A Landmark in Victorian Illustration. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2021.

Hardie, Martin. ‘The Moxon Tennyson, 1857’. First published in The Booklover’s Magazine. Reprinted in Edwardian Illustration. London: The Imaginative Book Illustration Society, 2005: 7–16.

‘Reviews.’ Art Journal (1857): 231.

[Rossetti, D. G.]. Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti to William Allingham. Ed. George Birbeck Hill. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1897.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857.

Created 30 August 2021