George Eliot’s writings were mainly issued without illustrations. Appearing in their initial form in Blackwood’s Magazine, a journal made up of dense columns of text, most of her fictions did not have the elaborate cuts that so typically accompanied the work of contemporaries such as Elizabeth Gaskell, Anthony Trollope, Charles Reade and W. M. Thackeray. The exception to this rule is Romola, which was published in 1862–3 in the Cornhill Magazine, with imposing designs by Frederic Leighton. The publisher, George Smith, saw an opportunity to enhance Eliot’s appeal by endowing her historical tale with images, but this was the only occasion when the author was directly involved in the discourse of the 1860s as she struggled to manipulate Leighton’s treatment of her text, a process, as several critics have observed, in which she ultimately shared authorship with the artist.

However, Eliot’s tales were illustrated in the subsequent editions that appeared in her lifetime. In 1869 Harper’s, the New York publishers, issued a new, library edition in which Robert Barnes and William Small were engaged to illustrate Silas Marner, Scenes of Clerical Life and Adam Bede. Barnes visualized the first two, but the most distinguished response was Small’s. This edition was not printed in England until the mid-1870s, when it appeared without a date as volume one of another library series by William Blackwood, and was later reprinted in 1880 and ’90s.

Small’s interpretation is composed of six full-page engravings and a title vignette; finely cut by J. D. Cooper and printed in bold but modulated black and white, his illustrations are striking examples of the poetic naturalism of the 1860s and exemplars of the artist’s imposing draughtsmanship. They are also, more tellingly, sensitive and suggestive readings of the literary source. Yet, in contrast to the extended criticism applied to Romola, they have never been the subject of analysis, and are considered here for the first time.

Class and Character

In contrast to Romola, Adam Bede was produced without any authorial involvement and was purely a private arrangement between the artist and the publishers; Eliot never mentions the artist and the reasons for Small’s being commissioned are undocumented, although it is possible to speculate on the Harpers’ reasoning. One reason is plain: he was selected because he was an accomplished practitioner of considerable reputation; in 1869 he had only five years’ experience of ‘drawing on wood’, but his published work was of outstanding quality and had appeared in most of the primary illustrated journals of Victorian England – notably Good Words, Once a Week, The Argosy and The Quiver. He had also contributed to gift books, among them Robert Buchanan’s North Coast (1868) and other anthologies such as Golden Thoughts from Golden Fountains [1867]. In each of these publications, Small provided poetic illustrations for diverse subjects; an artist of prodigious productivity who never resorted to formula, his illustrations were technically accomplished and conceptually advanced. He was offered the job by Harper’s, in other words, for his diligence, and was viewed as an artist who could probably be trusted to produce response.

At the same time, Harper’s may have registered the fact that Small was unusually well-suited as an interpreter of Eliot’s bucolic tragedy. Although his interests ranged from children’s books to Sensation novels such as Charles Reade’s Griffith Gaunt (1866), Small created a number of images in which he demonstrated a knowing awareness of the travails of the working classes; a self-made man who came from humble stock, his illustrations always displayed the humanity of someone who had personally experienced privation and economic struggle (Cooke, 88–94). This insider-knowledge, as it were, enabled him to show working class characters as dignified individuals rather than types, an approach exemplified by his showing of operatives being told to stand down in one of his illustration for The Quiver, There’s No Help for It (1869). Small’s vision of the humble loosely corresponded with Eliot’s, and in showing her personae he aimed to find equivalents to her text which were closely linked to her writing but drawn from his own visual treatments of the ‘lower orders’.

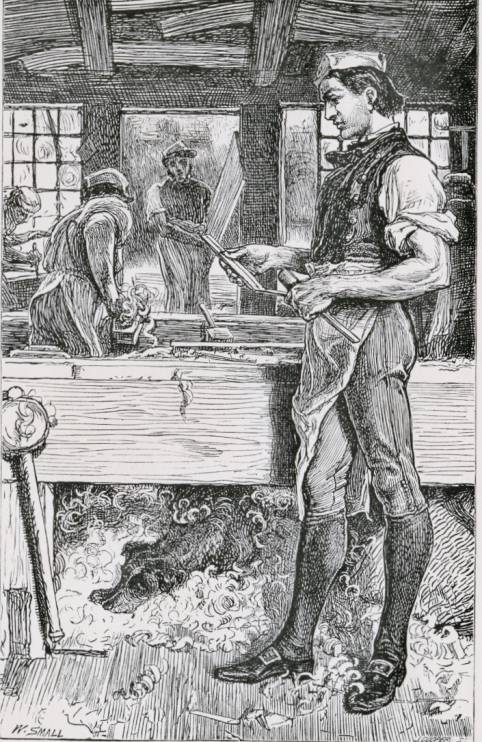

This match is exemplified by his visualization of Adam, fusing the author’s and artist’s notion of the working man. Eliot provides detailed specifications of his appearance and character traits when he is first seen in his carpenters’ workshop, noting when he speaks with such

a voice [that] could only come from a broad chest, and the broad chest belonged to a large-boned muscular man nearly six feet high, with a back so flat and a head so well poised that when he drew himself up to take a more distant survey of his work, he had the air of a soldier standing at ease. The sleeve rolled up above the elbow showed an arm that was likely to win the prize for feats of strength; yet the long supple hand, with its broad finger-tips looked ready for works of skill. In his tall stalwartness Adam Bede was an Anglo-Saxon … but his jet-black hair, made the more noticeable by its contrast with the light paper cap, and the keen glance of the dark eyes that shone from under strongly-marked, prominent and mobile eyebrows, indicated a mixture of Celtic blood. The face was large and roughly hewn, and when in repose had no other beauty than such as belongs to an expression of good-humoured honest intelligence. [1]

Small reproduces the details of this pictorial description in the frontispiece, establishing Adam as the prime character: his ‘well-poised’ height, ‘jet-black hair’ and ‘light paper cap’ are re-inscribed, and so are the ‘prominent’ eyebrows, large face and rolled-up sleeves. Faithful to the letter of Eliot’s text, Small mirrors the written details to provide an exact paratext; but he also amplifies the writing by applying his own understandings of how this ideal British workman – uniting the Anglo-Saxon and the Celt – should be shown.

Left: Frontispiece to Adam Bede. Middle: Scholar and Carpenter from Jean Ingelow’s Poems. Right: ‘There’s no help for it’ from A Muddy Day in Muddlesford. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Adopting a Pre-Raphaelite approach, he preserves the scene’s realism while manipulating aspects of space, scale and visual association, using them to project an idea of the character’s status as a proletarian hero. Of prime importance is his enhancement of Eliot’s picture of ‘a large-boned man nearly six feet high’; his Adam is a monumental figure in a foreshortened space which makes him seem colossal. Eliot’s focus is primarily on her eponymous creation as he struggles with his love affairs with Hetty and Dinah and his conflict with Arthur, and Small makes him into a titan – a man whose moral and spiritual largesse is symbolized by his dominating physical presence Eliot writes him as the quintessential decent man and Small, responding to the hints contained in the writing, makes his athletic build an exact visual concomitant of his ‘stalwart’ personality. He particularly accentuates the character’s traits by stressing the connection between robust physicality put to the service of manual work and ‘intelligence’. The focus here is on Adam’s muscular forearms and hands as signs of control and straightforward dealing. This motif recurs throughout Small’s designs – notably in his illustration of The Scholar and the Carpenter (Ingelow’s Poems, 1867) – and it is always used to connote a sort of uncomplicated, hard-working masculinity. Eliot’s constantly describes her hero as honest, and Small shows him, quite literally, as a man of integrity, a ‘safe pair of hands’.

Small moulds his physique to match and express his personality and as in all Pre-Raphaelite art, the outer becomes the expression of the inner. He intensifies this approach in subsequent illustrations. In Dinah and Adam (facing 442) the forthright carpenter is again depicted as a large and imposing figure with his ‘roughly hewn’ face (1) connoting his straightforward character as he proposes marriage, and in Adam Bede and Arthur Donnithorne (facing 261) his open face and muscular arms signal his honesty even as he kneels over the figure of his rival, whom he has knocked down in jealous rage.

This physicality dominates the illustrations and Adam’s status as an upright character whose form is a measure of goodness is especially accentuated by contrasting him with Arthur, Hetty’s seducer and the ruin of Adam’s plans. Small’s starting point, once again, is the author’s detailed pictorial data. Instead of having a ‘stalwart’ form, Arthur is described as a rather anonymous toff: ‘If you want to know more particularly how he [looks]’, Eliot writes disparagingly

Call to your remembrance some tawny-whiskered, brown-locked, clear complexioned young gentleman, whom you have met with in a foreign town … well-washed, high-bred, white-handed …I will not be so much of a tailor as to trouble your imagination with the difference of costume, and insist on the striped waistcoat, long-tailed coat, and low top-boots. [50]

Although she constantly tries to modulate her writing of Arthur – claiming that his behaviour is thoughtless rather than malign – she always presents him as a type of arrogant privilege, inscribing his superficiality in the lights colours the Victorians associated with shallowness, ‘brown-locked’ and ‘tawny’ in contrast to Adam’s determined black, ‘white-handed’ in opposition to Adam’s muscular arms and hands, and dressed in decorative clothes in contrast to his his rival’s rolled-up sleeves. Throughout the novel, Arthur’s physique is at odds to Adam’s: strong appearance connotes a strong character, while Arthur’s feminized appearance symbolizes his moral weakness.

In the only illustration of Arthur and Hetty’s love-making, In the Wood (facing 117), Small vividly conveys Arthur’s shallowness by showing his figure as a delicate and insubstantial. In contrast to Adam’s athletic gait (facing 1), he holds his top-hat behind him and as he leans forward to kiss his beloved creates an outline both sinuous and broken, a device which, unlike the near-geometry of Adam’s outline, strongly suggests his lack of consistency and substance.

Small also draws a telling contrast in Adam Bede and Arthur Donnithorne(facing 261). In this design the opposition is almost diagrammatic: Adam’s working clothes are opposed to Arthur’s carefully-specified waistcoat (which preserves the stripes), gaiters and buckled shoes, and the carpenter’s imposing presence is further heightened by contrasting his taut pose with his rival’s prostration, whose physical insignificance is amplified by the extreme foreshortening of his unconscious body. Small thus focuses Eliot’s dramatic tension between the robust and good-thinking Adam and the insubstantial and unreliable Arthur.

Left: Adam Bede and Arthur Donnithorne. Right: In the Wood. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

His illustrations point to the novel’s central tension, but also have the effect of amplifying Eliot’s exploration of class-conflict. Crystallizing the opposition of the two main characters, Small re-figures the novel as a struggle between privilege and peasantry in which he elides the complications of the situation and offers in its place his own reading of the class-theme as a matter of exploitation and resistance. Eliot tries to avoid simplification, but Small shows no sympathy whatever for privilege and the status quo and conceives the two characters, which become emblems of their class, in terms of a conflict not only between individuals but value-systems. If Eliot’s approach is a subtle modulation between criticism and affirmation in the ambivalent manner of mid-Victorian criticism, Small’s is essentially what we would call a Marxist or at least a Socialist interpretation which champions the workers.

At several key points the artist’s focus diverges from the author’s, and is different from her writing of Hetty Sorrel. Eliot’s attitude to Hetty is deeply ambivalent. Although she presents her as a victim, she also writes her as a ‘distracting kitten-like maiden’ who is viewed by her aunt Poyser as a ‘little huzzy’ (70–1). The implication is that her attractiveness absolves Arthur from at least some of the implications of his actions; somehow, she is as almost as much to blame as he is. For Small, on the other hand, there is no doubt that Hetty is purely the innocent, acted upon rather than acting: though Eliot stresses her beauty, in the illustrations she is practically invisible, only appearing In the Wood (facing 117) as an object to be kissed. Eliot describes her portrait and demeanour, but in the illustration her face is obscured, re-casting her as an anonymous lower-class girl, interchangeable with all others, and subject to the authority and exploitation of her social superiors. If Arthur is a type, then Hetty is too, shown only as an emblematic figure – a helpless innocent enmeshed in an exploitative class system as surely as the main character in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, a novel which owes a considerable debt to Eliot’s.

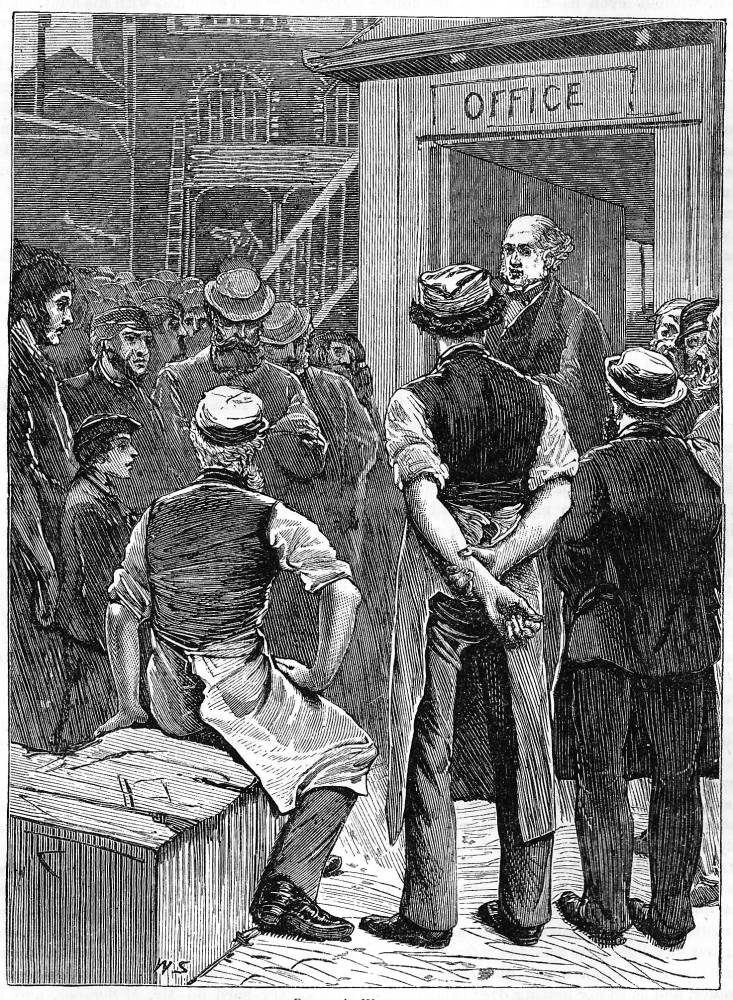

Small’s sympathy for Hetty’s predicament and the sufferings of the peasantry is also suggested by the emphasis of other illustrations. This is partly a matter of valuing the ordinary over the exceptional. It is noticeable, for example, that Small re-inscribes in detail the author’s descriptions of working-class environments. Adam’s workshop, with its busy productivity (facing 1) is carefully reproduced, an assertion of its importance, while there is no illustration depicting the Donnithornes’ home life. Important too is the selection of weighted moments. Small chooses to focus on the angry exchange between the old squire and Mrs Poyser – a dramatic crisis revealing the proprietor’s unfeeling attitude as he suggests a change that could lead to the family’s eviction. Eliot describes in painful detail Mrs Poyser’s confronting of the indifferent squire, chasing him into the yard as he tries to escape while telling him a few home truths:

‘You may run away from my words, sir, and you may go spinnin’ underhand ways o’ doing us a mischief … but I tell you for as we’re not dumb creaturs to be abused and made money on by them as ha’ got the lash i’ their hands … An’ if I’, th’ only one as speaks my mind, there’s plenty o’ the same way o’ thinking [it] …’ [302]

This is a direct attack on the cruelties of the social system, and Small makes the scene as uncomfortable as possible (facing 302): Mrs Poyser is shown haranguing the squire as he struggles to escape, beckoning the servant who is exercising his pony, the geese and dog are depicted as they noisily respond to the shouting, while other servants come out to listen to the row. The sound of the scene is accentuated to express the discord, and Small adds other small details: the four way movement (the squire’s embarrassment, Mrs Poyser coming after him, the pony being led toward him and the milling of the geese and dog) conveys inner agitation, and, most tellingly of all, the fact that the squire’s back is turned to the viewer. We do not see his face and the implication is that he is – or should be – ashamed. Conversely, Small could be suggesting that the squire’s turning away is a visual metaphor, a sign of how little he cares about the Poysers’ fate.

Left: Dinah and Adam. Middle: Mrs Poyser and the Old Squire. Right: Dinah and Hetty in the Prison. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Small’s reading of Adam Bede becomes in these ways a radical – perhaps even a Radical – amplification of the novel’s exposure of class exploitation. Eliot encodes her critique in the narrative and its situations, but Small is far more explicit, privileging those elements which he manipulates to create his own, socially-minded critique of social rank and ‘order’; as Paul Goldman remarks, his art is a matter of ‘real character … sincere and direct in feeling’ (140). Developed in Adam Bede, this emphasis prefigures later developments in Small’s career; always concerned with the sufferings of the poor, his social realism reappeared in illustrations throughout the late sixties and seventies and in the eighties he went on to become of The Graphic’s most effective commentators, providing painful, revelatory images of the lot of the great British poor which compare with cuts by Frank Holl and Hubert von Herkomer (Cooke, 106–111).

Small and Psychological Drama

Small’s emphasis on the class struggle foregrounds the novel’s social themes and makes it seems more obviously a left-leaning production than the writer may have intended. His work is a prime example of the way in which an illustrative series can appropriate a text, re-orientating the words to match the illustrator’s, rather than the author’s artistic vision. This is the very conundrum that haunted Victorian writers who kept artists under their control because they feared they would usurp their authority, and Small’s heightening of Eliot’s social conscience, making it seem like polemic, is a prime example of a struggle for power in which the artist gains pre-eminence.

On the other hand, Small’s visualization of Eliot’s psychological case-studies and emotional situations is a well-realized re-writing in which the illustrations and the text merge and intermingle to create a harmonious whole in service of the characters’ inner lives. Eliot describes and analyses the main players’ psychologies in great detail, and Small perfectly complements this emphasis in a series of expressive manipulations which focus on facial expression and gesture. Adam and Arthur’s dangerous encounter exemplifies the interplay of text and design. The climax, depicted in both, is the moment after Adam has felled his rival, who lies as if dead:

But why did not Arthur rise? He was perfectly motionless … Adam shuddered at the thought of his own strength , as with the oncoming of this dread he knelt down by Arthur’s side … There was no sign of life: the eyes and teeth were set. The horror that rushed over Adam completely mastered him … He made not a single movement, but knelt like an image of despair gazing at an image of death. [262]

Small visualizes the mechanics of the scene in detail but more telling is his emphasis on the key terms: ‘shuddered’, ‘dread’, ‘horror’ and ‘despair’. The indices of Adam’s state of mind are powerfully re-inscribed in his immobile gesture and especially in his facial expression: grimly set, it conveys the very ‘image of despair’ while suggesting his panic as he realizes he may be Arthur’s murderer.

Small excelled at representing suffering, an interest featuring throughout his work, and here his capacity to condense a complex state of mind in a single portrait is given a memorable form. In Dinah and Hetty in the Prison (facing 390), by contrast, the emphasis is purely on significant gestures. Eliot only notes that Hetty was ‘clasped in Dinah’s arms’ (390), but Small shows it a moment of tragic intensity as Hetty, accused of infanticide and her life in ruins, is momentarily consoled by the embrace. Small does not show the face of the ‘wretched lost one’ (390), but conveys the moment of intense feeling purely in the form of the clasped figures, locked in a drear cell. This is a variant on Small’s many other images of prostrate or suffering women, and it is interesting to compare his image of Hetty and Dinah with his illustration of Mrs Gaunt’s anguish in Griffith Gaunt and of a male character in Deliverance.

Deep feeling of another sort is visualized in the final illustration, Dinah and Adam (facing 442). This time Small focuses on the gestures of love, with the two characters holding hands and Adam looking directly into her face. Eliot writes this scene as a redemptive event in which the worries of the past can be dismissed, and Small provides a visual reimagining in strict accordance with the author’s resonant words, they ‘sat looking at each other in delicious silence, – for the first sense of mutual love excludes other feelings: it will have the soul all to itself’ (443). Eliot’s writing contains several tender encounters, and it is interesting to compare Small’s visualization of a love-scene with Leighton’s treatment of the The First Kiss in Romola; though the characters and settings are dissimilar, both provide an incisive representation which captures the intensity of the moment.

Taken as a whole, Small’s illustrations for Adam Bede are both paratextual and interpretive: they reinforce aspects of the writing and work to re-orientate our understanding of the social theme. Although there are only six full-page engravings, their contribution to the reading experience is considerable, defining the appearance of the characters in consistent detail, illuminating their innermost feelings, and adding a new sense of outrage to the theme of class-tension. Eliot believed illustration could only be a sort of ‘overture’ to the text, a secondary device; but Small, like Leighton, offers so much more than supporting material.

Works Cited

Cooke, Simon. ‘“Sustained Power”: the Life and Art of William Small.’ The IBIS Journal 6 (2018): 87–139.

Eliot, George. Adam Bede. Edinburgh: William Blackwood, [1878].

Eliot, George. ‘Romola.’ Cornhill Magazine, The. London: Smith, Elder, 1862–3.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996.

Last modified 8 January 2019