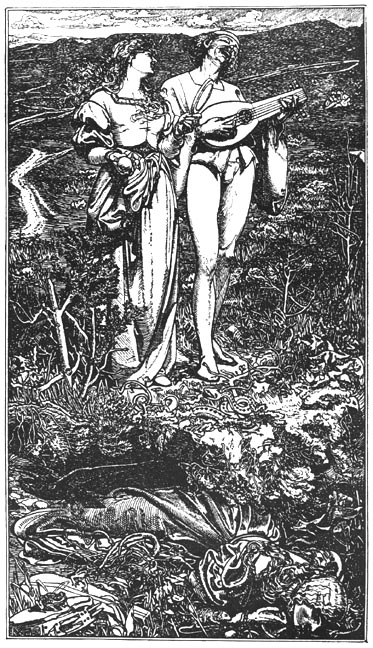

Amor Mundi, 1865. Left: Brush and ink over traces of graphite on cream paper. 6 3/4 x 3 7/8 inches (17.1 x 9.9 cm) – image size. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, accession no. 29691. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada (right click disabled; not to be downloaded). Right: Wood engraving by Joseph Swain in black ink on cream paper. 6 7/8 x 3 7/8 inches (17.4 x 9.8 cm) – image. Private collection, image courtesy of the author. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

Amor Mundi was the illustration design Sandys most preferred and is a masterpiece of 1860s illustration, evincing a close collaboration between artist and engraver. The title translates from the Latin to mean "Love of the World." Betty Elzea has described the scene shown in the drawing as follows:

Two figures, of a man and woman in costume in the style of the Renaissance, stroll along a path which recedes into the distance on the right, then sweeps over to the left distance on rising ground. In the left distance, on the hillside is a courting couple seated on the ground (somewhat out of scale, alas). Behind are low hills and a cloudy sky. The strolling man is playing a stringed musical instrument and singing. The woman holds a hand-mirror in one hand and an apple in the other. At their feet is a snake coiling on the edge of a hollow in the ground. In the hollow, unseen by the couple, lies the corpse of a young woman whose face rest on a mirror in the left foreground. A rat sits beside her lifeless arm, a snail glides towards the mirror, and a large black carrion crow flies away from her to the right. Lying on the ground in the right foreground are a stringed instrument, and a tambourine, upon which two frogs sit. [221-22]

Elzea also points out how effectively this work "embodies all the symbolism of a Vanitas, in harmony with the moralizing tone of the poem: youth, vanity, temptation, pleasure, folly, and their inevitable consequences - death, and decay" (222).

The drawing and engraving capture well the moral of Christina Rossetti's poem "Amor Mundi," which shows how easy it is to get caught up in a cycle of sin, inevitably leading to hell, from which there is no turning back.

Amor Mundi

"Oh where are you going with your love-locks flowing

On the west wind blowing along this valley track?"

"The downhill path is easy, come with me an it please ye,

We shall escape the uphill by never turning back."

So they two went together in glowing August weather,

The honey-breathing heather lay to their left and right;

And dear she was to dote on, her swift feet seemed to float on

The air like soft twin pigeons too sportive to alight.

"Oh what is that in heaven where gray cloud-flakes are seven,

Where blackest clouds hang riven just at the rainy skirt?"

"Oh that's a meteor sent us, a message dumb, portentous,

An undeciphered solemn signal of help or hurt."

"Oh what is that glides quickly where velvet flowers grow thickly,

Their scent comes rich and sickly?"—"A scaled and hooded worm."

"Oh what's that in the hollow, so pale I quake to follow?"

"Oh that's a thin dead body which waits the eternal term."

"Turn again, O my sweetest, — turn again, false and fleetest:

This beaten way thou beatest I fear is hell's own track."

"Nay, too steep for hill-mounting; nay, too late for cost-counting:

This downhill path is easy, but there's no turning back."

This illustration appeared in Volume One of The Shilling Magazine, published in May 1865, opposite page 193. The woodcut has been highly praised by many scholars. Walter Sickert wrote in The Burlington Magazine: "Amor Mundi by Frederick Sandys is perhaps the finest example of perfectly suitable expression in a wood cut line of modern times" (150). Forrest Reid provided his own interesting interpretation of the illustration and felt the young woman holding the mirror, and the corpse, were one and the same: "The Amor Mundi is a beautiful, slightly unpleasant, and extraordinarily suggestive drawing, depicting two lovers, strolling down the easy path of sensuality to the hidden hollow where death lies waiting. Not Death as he is usually symbolized, but the dead and corrupted body of this very woman, now hanging in foolish soulless laughter on her lover's arm. A rat gnaws at the tattered wrist of the corpse, whose flesh Christina describes as 'pale,' but to which Sandys has given the terrible hues of putrefaction" (60).

J. M. Gray in The Century Guild Hobby Horse gave the fullest description and interpretation of this illustration:

Another superb design is that illustrating Miss Rossetti's lovely poem "Amor Mundi." Here we see a white road winding through a stretch of upland moor, beyond which billowy white clouds are sweeping across the sky. In the midst of the foreground, which, with its varied herbage and its stunted brushwood, is treated with singular elaboration and truth to nature, is the lady of the poem, pacing lightly in company with the lover who has beguiled her from treading the steep arduous path which leads skyward. Her luxuriant hair floats round her neck, her laughing rounded cheek meets the summer breeze; in one hand she holds a circular mirror which flashes back her loveliness, and in the other is the apple of sweet forbidden pleasure. Her companion is by her side; his head gaily raised with open mouth, as he sings and touches the lute whose notes accompany his voice. In the immediate front, unseen by the pair, but directly in the path which they follow, is coiled a deadly snake, with forked and threatening tongue; and beside a shadowed hollow, filled with blackest depths of unsunned water, is "a thin dead body," passing from beauty into ashes, with sunken cheek and withered hand, lying so still that a tiny shrew-mouse crouches undisturbed beside it, while toads of grotesque form, and with gleaming eyes, squat among the strings of the instruments of music that are brought low and rest silent on the grass, and a raven flutters away upon black widespread wings. [151-52]

Joseph Pennell felt that in Sandys's work he had been influenced by illustration in the manner of the Germans of the fifteenth and sixteenth century but also by later German artists like Alfred Rethel:

There is no doubt that Sandys surpasses in technique all the artists of the best period of English draughtsmanship. His designs possessed the same elevation of ideas which was so markedly the characteristic of the Germans, and was the outcome of the spirit of their age. But there is no question that technically many parts of this drawing Amor Mundi are quite equal to Dürer's work; while others are expressed in a manner absolutely unknown to Dürer. There is a feeling of colour throughout which Dürer never attempted on the wood, because he knew it could not be retained in the cutting…. No one has ever drawn better for process than Sandys" [Pen Drawing, 193]

Bibliography

Amor Mundi. National Gallery of Canada. Web. 21 August 2025.

Elzea, Betty. Frederick Sandys 1829-1904. A Catalogue Raisonné. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., 2001, cat. 2.B.67, 221-22.

Engen, Rodney. Pre-Raphaelite Prints. London: Lund Humphries, 1995, 111-12.

Gray, John Miller. "Frederick Sandys and the Wood-Cut Designers of Thirty Years Ago." The Century Guild Hobby Horse III (October 1888): 147-56.

Pennell, Joseph. "A Golden Decade in British Art." The Savoy I (January, 1896): 122.

_____. Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmanship. A Classic Survey of the Medium and Its Masters. New York: Macmillan, 1920.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Sixties. London: Faber & Gwyer Limited, 1928.

Rossetti, Christina. "Amor Mundi." Shilling Magazine "A new edition." London, 1865. [The original image on this page was scanned from this source by George P. Landow.]

Schoenherr, Douglas E. "Frederick Sandys's Amor Mundi." Apollo Magazine CXXVII (May 1988): 311-18.

Sickert, Walter. "Woodcuts of the 'Sixties at the Tate." The Burlington Magazine XLII (March 1923): 148-50.

Created 7 November 2009

Last modified 8 December 2025