eatrix Potter (1866–1943) is best known as the author of The Tale of Peter Rabbit(1902), the first in her series of 23 children’s books. Potter’s installment in the nursery has overshadowed her achievement as a multi-faceted visual artist. To the field of children’s literature, Potter brought her skill as a naturalist, creating book illustrations for her charming tales. Potter fills her storybooks with talking animals—rabbits, mice, squirrels, cats, a frog, a hedgehog, a badger, and a fox—that live in gardens, woodlands, ponds, and meadows. A skilled observer and illustrator of the natural world, Potter follows the Sixties school of poetic realism in England associated with the Pre-Raphaelite painter turned illustrator John Everett Millais, whose work she greatly admired.

Drawing from Childhood

lthough Potter lived in London at No. 2 Bolton Gardens, West Brompton, the Potter family summered in Scotland and the Lake District where Potter drew out-of-doors. From the age of eight, she filled her sketchbooks with drawings and watercolors of a variety of plant and animal species. Young Beatrix and her brother, Bertram, were known to smuggle some of these live and dead animals—rabbits, owls, bats, mice, and even a fox—into their upper-floor nursery; while the live animals became their pets, the dead ones could be skinned to facilitate accurate anatomical drawings. With the eye of a naturalist, Potter also studied plant specimens under brother Bertram’s microscope, drew meticulously from models displayed at the Museum of Natural History and the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert, London), and made natural history studies of plant life that she observed in their natural habitats, a skill she carried into book illustration.

Although Potter did not have any formal artistic training, she received the Art Student’s Certificate from the Science and Art Department of the Committee of the Council on Education in 1881 (Linder, Art x). To Potter, more valuable than the certificate—which affirmed her skill in free hand and model drawing and linear perspective—was a compliment that she received from Millais, a close family friend whose studio she often visited with her father, Rupert Potter (a lawyer who was also an amateur photographer and artist). Potter recounts in her journal entry of 13 March 1896 (the day of Millais’s death): “I shall always have a most affectionate remembrance of Sir John Millais … He gave me the kindest encouragement with my drawings . . . but he really paid me a compliment for he said that ‘plenty of people can draw, but you and my son John have observation’” (Linder, Journal 418). According to her biographer Linda Lear, Potter treasured Millais’s accolade “for the rest of her life” (Beatrix 45) because Millais “made the distinction between those that could merely draw and those whose drawings had ‘the divine spark of’ observation” (96).

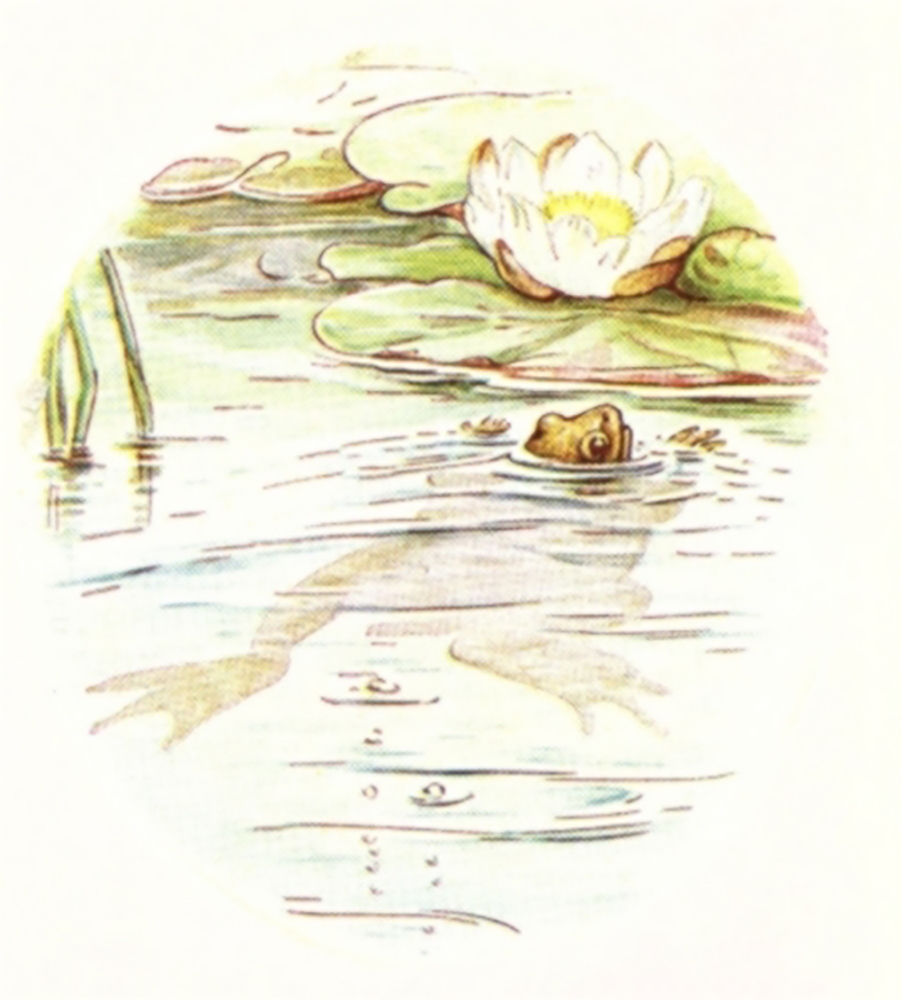

Potter drew the physical world with such accuracy and attention to detail that her naturalist studies resemble photographs infused with a spark of inspiration. She also followed in the tradition of anthropomorphism in Victorian illustration evident in the earlier work of Harrison Weir, John Tenniel, and Randolph Caldecott (e.g. his frog character in The Frog He Would A-Wooing Go[1883] is often considered a model for Jeremy Fisher the frog). Aligning the behavior of humans and animals, Potter allowed her characters to speak, set them in social situations, and dressed them in clothes. However, Potter never covered an animal’s defining features or altered animal anatomy. Indeed, when her publisher, Frederick Warne, questioned the yellow-green coloring of the skin of her frog character Mr. Jeremy Fisher, Potter brought her live model to the publisher’s London office in a jam jar to demonstrate the authenticity of her color palette. Authenticity mattered to Potter. No doubt she would have been pleased that in 2002 to mark the centenary of the first publication of Peter Rabbit by Frederick Warne & Co., Warne (now under the Penguin Books imprint) reset the text and made new reproductions of Potter’s illustrations for the entire storybook series, using modern technological advances to replicate the colors and details of her original watercolors.

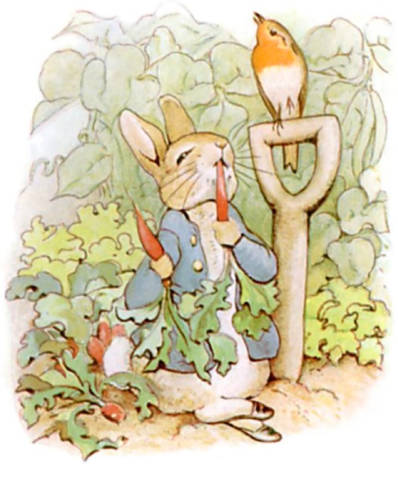

Left: Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail, who were good little bunnies, went down to the lane to gather blackberries. Middle: First he ate some lettuces and some French beans; and then he ate some radishes. Right: Peter asked her the way to the gate, but she had such a large pea in her mouth that she could not answer. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Naturalist Artist and Illustrator

otter made her mark as a children’s author and illustrator, but her first ambition was to become a naturalist artist. In the 1890s, she became fascinated by mycology and pursued her passion in the hope of publishing her breathtakingly detailed watercolor studies of fungi and mushrooms in a natural history book. To ensure scientific accuracy, Potter compared the specimens she gathered on her expeditions to those in museum displays and studied her specimens under a microscope before she classified them. In 1896, Potter’s uncle arranged for Potter to show her portfolio of over 250 specialized studies of fungi and mushrooms to the botanists and director of the Royal Botanical Gardens of Kew. The male scientific community patronizingly dismissed Potter because of her gender and her age (although she was thirty years old) and because some of her drawings illustrated theories from her own scientific experiments (notably lichen as a species of fungi living in close association with algae). These drawings anticipated the findings of the Linnaean Society, a London biological society founded in 1778, and were later proven to be correct. Potter’s ambition to be a naturalist artist came true posthumously when, in 1967, mycologist W. P. K. Findlay used 59 of Potter’s drawings to illustrate Wayside and Woodland Fungi, a natural history book. During her lifetime it was through children’s book illustration that Potter realized her dream to present nature lessons to a wide audience. She achieved success as an author-illustrator because, by the 1890s, women had already established themselves as writers and no longer needed to hide under pseudonyms, as her literary sisters had done in the 1840s and 1850s (for example, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë published under the names Currer, Acton, and Ellis Bell). Moreover, the field of book illustration welcomed women artists into its ranks, particularly for books geared for women and children.

Naturalism in Book illustration

For her storybook series, Potter drew upon what she called “picture-letters” (Linder, Journal 250) written to the children of her former governess, Annie Carter Moore; for example, she based her first story, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, on an illustrated letter to five-year-old Noel Moore written in Eastwood, Dunkeld and dated September 4, 1893. In her book illustrations, Potter exhibits many of the features that define the work of Sixties artist turned illustrator John Everett Millais, her artistic mentor. Potter favored figure over background, drew with lifelike realism, and showed a keen observation of nature as well as an allegiance to geographical sites.

Left: The Miller's Daughter from the Moxon Tennyson (1855). Right: Ophelia. Sir John Everett Millais. 1851-52. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Tate Britain, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

She admired Millais’s early style, exemplified in Ophelia, which depicts the drowning Ophelia, who has taken her life upon learning that Hamlet has murdered her father in Act IV, Scene vii of Shakespeare’s play. Millais, who began the canvas by painting the background out-of-doors at Ewell in Surrey, gave great attention to the rushes and flowers surrounding Ophelia’s floating figure, the focus of the canvas. Millais rendered the roses, nettles, pansies, and daisies with rich botanical detail. Potter likewise set her work in identifiable locations and drew from nature. For example, Derwentwater and St. Herbert’s Island in the English Lake District are the settings for The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin (1903). Esthwaite Water, also in the Lake District, is the place where Jeremy Fisher in The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher (1906) makes his home.

While creating her tales, Potter also called upon her extensive portfolios of drawings of animal and plant life that she drew out-of-doors and executed with scientific acumen. For example, a watercolor of an orange-red rose hip with an authentically rendered tear-like seed receptacle that Potter designed at the age of twelve informs a drawing of Squirrel Nutkin as “he gathered robin’s pincushions off a briar bush” (37) in The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin; such naturalistic details including mushrooms that she observed under a microscope enrich her tale about a saucy red squirrel named Nutkin who narrowly escapes the wrath of an owl, named Old Brown, and loses his tail. Sketches of live frogs with webbed feet and bulging eyes, positioned variously on the page, and of water lilies with their white flowers and spongy green leaves appear in book illustrations for The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, a tale of an adventurous frog nearly swallowed by a large trout when he goes fishing for minnows to make a feast for his friends. And Potter’s illustrations of her most famous rabbit characters from The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) and its sequel The Tale of Benjamin Bunny (1904)—the first about a mischievous rabbit who ventures into Mr. McGregor’s vegetable garden and loses his clothes, only to retrieve them in the story’s sequel with the help of his cousin, Benjamin—exhibit the correct anatomical features of her own pet Belgian rabbits, Peter Piper and Benjamin Bouncer.

Left: Squirrel Nutkin Gathering Pincushions from a Briar Bush. Middle: Mr. Jeremy Bounced Up to the Surface of the Water. Like a Cork. Right: Don't go into Mr. McGregor's garden. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Potter gives Peter Rabbit a trademark blue jacket with shiny brass buttons, but the jacket does not cover his fluffy white tail, light brown fur, white underbelly, and haunches—features that define him as a rabbit. In The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Peter’s three sisters—Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail—wear pink-red cloaks in the illustration where Mrs. Rabbit warns her four children not to venture into Mr. McGregor’s garden, but she disrobes the rabbits in a subsequent illustration of the three sisters picking wild blackberries. As a result, Potter displays the rabbits’ light brown fur and the anatomy of their front paws fully extended as they busily pick fruit from a skillfully rendered blackberry bush. Potter includes the compound leaves of the shrub, with five or seven leaflets, and the prickles as well as the deep purple-black hued blackberry fruit, which grow in clusters on the shrub as in nature.

Arguably the most famous Peter Rabbit illustration of Peter overeating French beans, lettuces, and radishes in Mr. McGregor’s garden is rich in naturalism. For this tale set in Scotland’s Perthshire, around Dunkeld, Potter skillfully renders the vegetables as well as the rabbit and the robin perched on a spade in this English garden. Behind Peter are long, thin green French beans, leafy lettuces in a yellow-green hue, and tapering red radishes with large green leaves. The red-breasted robin also exudes lifelike realism. Potter frequently drew live and dead birds that she observed in nature, such as in her 1902 “Studies of a Dead Thrush ‘Picked up in the snow’” (Linder and Linder 178). She carried her skill in executing the bill and feathers and anatomical shape of a bird into this illustration of a European robin with a black bill and eye, orangey-red breast and face, and whitish belly. Potter’s attention to naturalism in the plant and animal world exhibited in Peter Rabbit, Jeremy Fisher, and Squirrel Nutkin recalls the school of representational realism in book illustration associated with Millais and extends beyond these works and across her entire storybook series,

Symbolism in Book Illustration

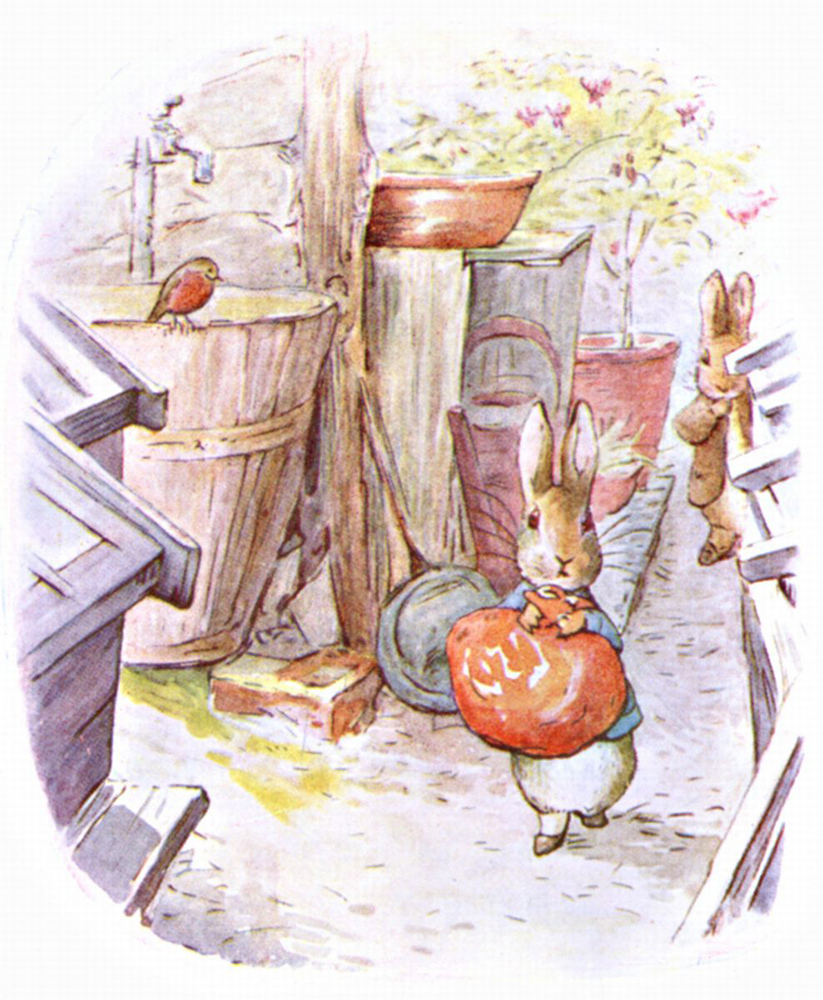

he robin in this well-known garden plate, a bird commonly found in an English garden, is a recurring symbolic detail not only in The Tale of Peter Rabbit but also The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, which she set in Fawe Park in Keswick in the Lake District. The red-breasted robin, never mentioned in either text, becomes a visual motif for Peter’s lapsed conscience. For the 2002 reprinting of the tale, which restores six plates “sacrificed in 1903 to make space for illustrated endpapers” (“Publisher’s Note” 2002), the robin appears six (rather than five) times. In each appearance in Mr. McGregor’s garden—where Mrs. Rabbit warns all the bunnies not to go—the robin witnesses Peter getting into “mischief” (12). The black-eyed robin, “boldly observant on the spade while Peter overeats himself of radishes” (22; Lane 71), next watches gluttonous Peter searching for parsley to cure his tummy ache (25); losing “one of his shoes among the cabbages, and [then] the other shoe amongst the potatoes” (30-33); standing behind Peter, “out of breath and trembling with fright” (46) after narrowly escaping from Mr. McGregor by jumping out a window, knocking over three plants in the process; and in its sixth appearance perching on Mr. McGregor’s pathetic scarecrow made out of Peter’s lost shoes and jacket (61), seemingly aware that “It was the second little jacket and pair of shoes that Peter had lost in a fortnight!” (64). There is nothing surprising about a robin lingering in a vegetable garden. But the robin’s inclusion in up to six scenes in Peter Rabbit makes the robin a visual moral.

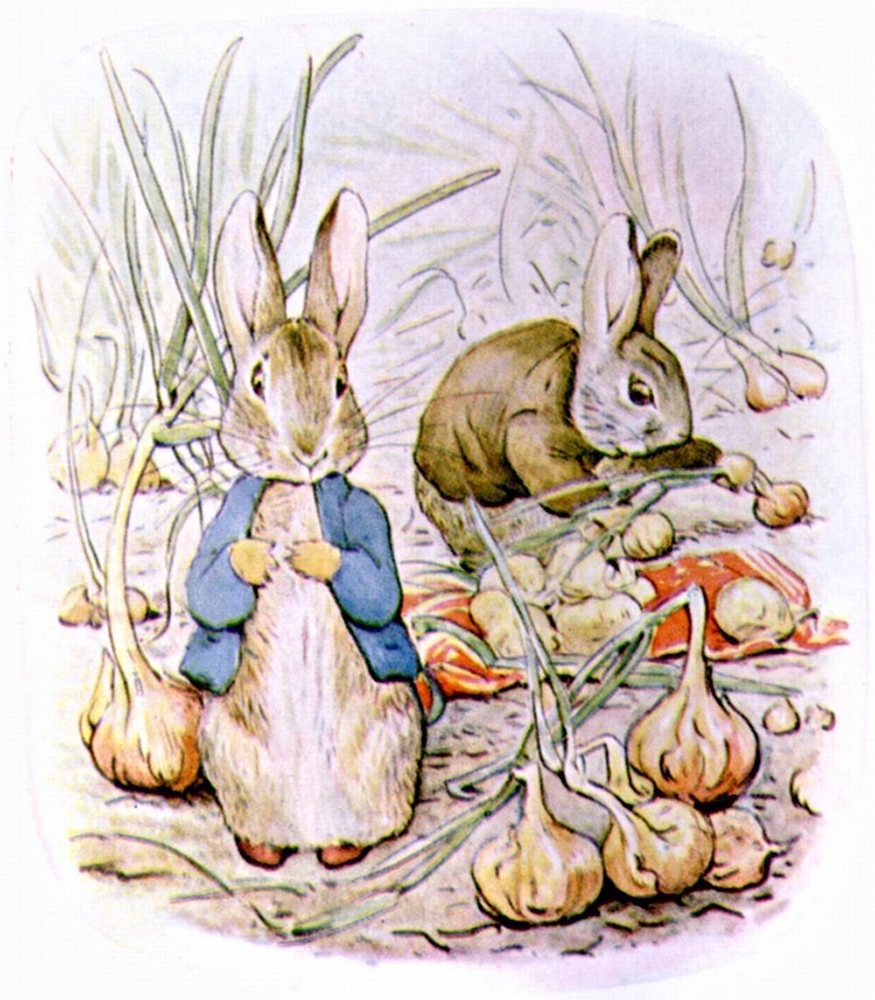

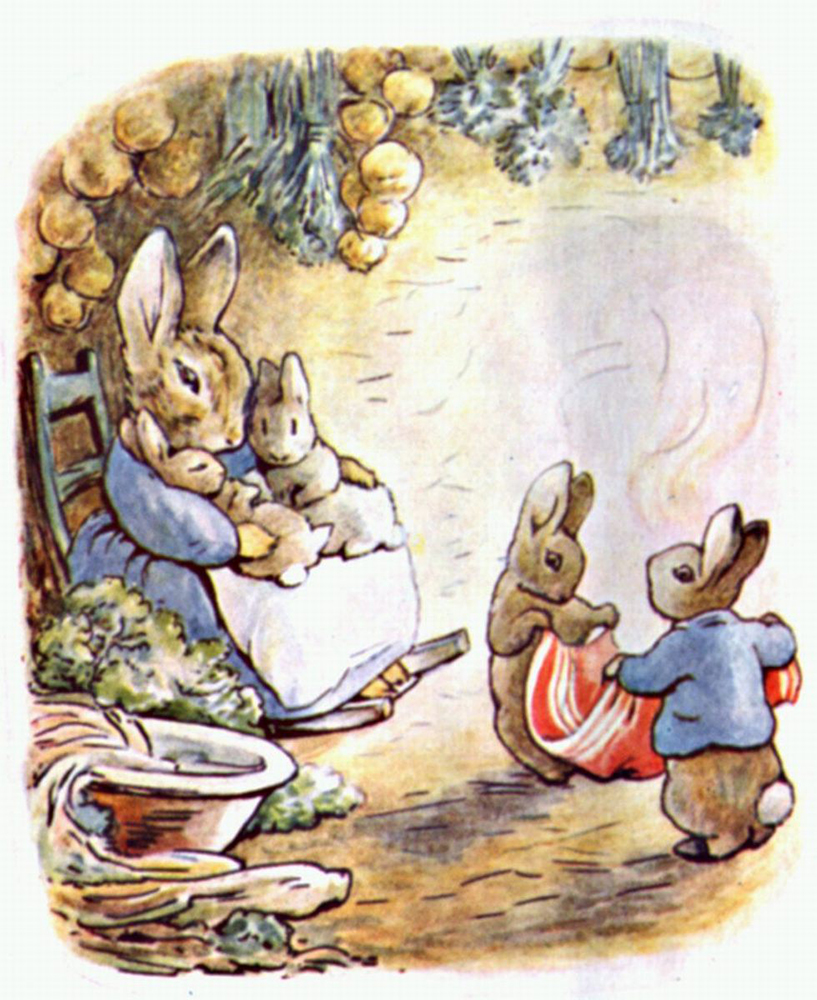

Left: Peter Heard Noises Worse Than Ever, His Eyes Were as Big as Lolly-Pops. Middle: Then He Suggested They Should Fill the Pocket-Handkerchief with Onions, as a Little Present for his Aunt. Right: Cotton-tail and Peter Folded Up the Pocket-Handkerchief. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

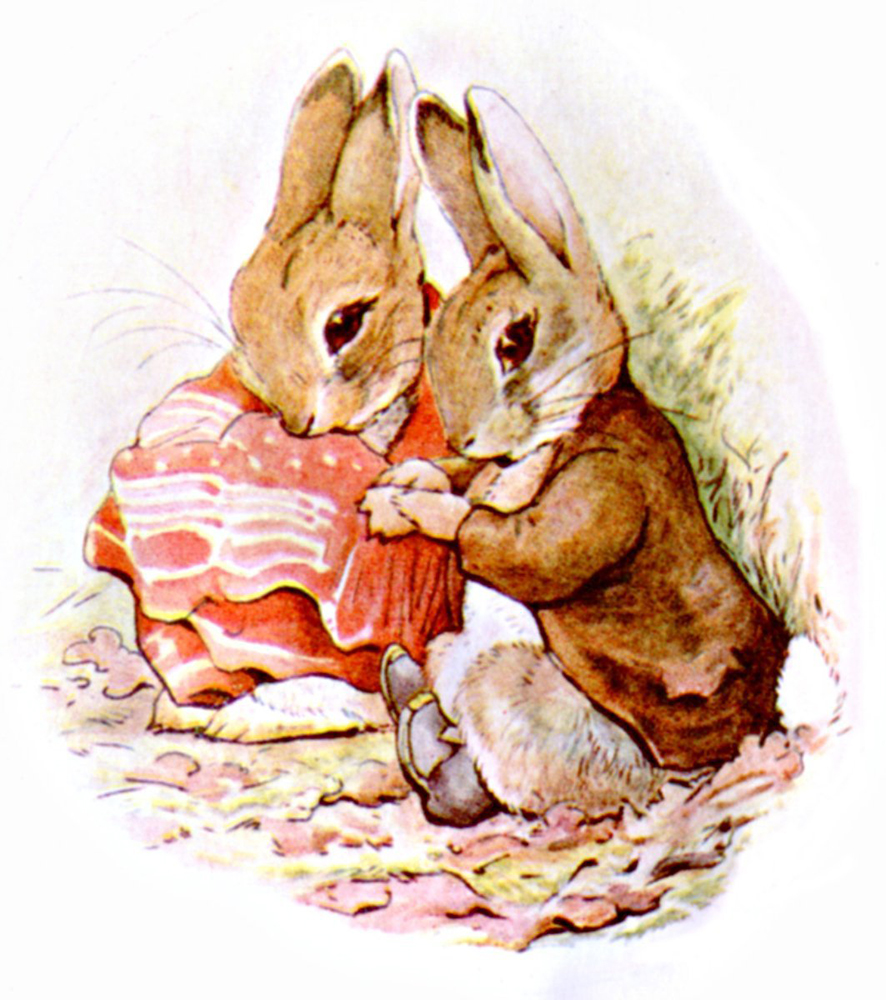

Peter twice encounters the robin when he returns to Mr. McGregor’s garden with Benjamin to retrieve his clothes in The Tale of Benjamin Bunny. Both of the robin’s appearances come late in that story. The two bunnies retrieve Peter’s belongings, gather onions as a present for Peter’s mother, and make their way to the garden gate. Peter feels uneasy: “Peter heard noises worse than ever, his eyes were as big as lolly-pops!” (39). In the accompanying picture, the red-breasted robin, perched on a water barrel, looks directly at Peter and intensifies the fright in Peter’s “lolly-pop” eyes and tense whiskers and ears. The robin—whom we learn is named Cock Robin in a subsequent tale, The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle (1905)—becomes a potent moral reminder to both naughty rabbits. In its second appearance, the robin stares at Peter and Benjamin whose long ears hang down in shame; the rabbits are holding their sore backsides after a whipping from Benjamin’s father, old Mr. Benjamin Bunny, after he helps them escape from a wily cat that traps them under a basket. In both tales, the robin is a silent observer standing for the conscience the rabbits may ignore but that never leaves them.

Little Benjamin Sat Down Beside His Cousin.

A second symbolic detail, a red pocket-handkerchief, also becomes a visual motif that shapes the plot of Benjamin Bunny and transforms from a symbol of shame to redemption. In this tale, Peter looks “poorly” (15) in ill-fitting garb literally taken from his mother’s back, marking him a naughty rabbit. However, the red handkerchief gains symbolic complexity once Peter retrieves his clothes, and Benjamin suggests they fill it with onions that Potter renders with great skill. Potter captures the bulbous shape of the onions and the reddish-gold hue of the skin of a yellow onion as well as the shape of its long, flat green leaves that grow from the bulb’s stem and authentically twist and bend as in nature. Thus, Potter grounds this whimsical picture of rabbits gathering onions with botanical realism. Even though the rabbits leave McGregor’s garden in disgrace, Peter’s “mother forgave him, because she was so glad to see that he had found his shoes and coat. Cotton-tail and Peter folded up the pocket-handkerchief, and old Mrs. Rabbit strung up the onions and hung them from the kitchen ceiling” (57). The folded up handkerchief, which Mrs. Rabbit can use once again as a head covering, symbolically highlights Peter’s redemption.

Elements of nature join with the whimsically clothed animals to advance the morals of Potter’s stories that brim with naturalistic details executed with near photographic realism. Potter foremost brings scientific acumen to her watercolor illustrations that show her keen skill in “observation,” which distinguishes her contribution to the field of Victorian book illustration.

Works Cited

Golden, Catherine. “Beatrix Potter: Naturalist Artist.” Woman’s Art Journal (Spring/Summer 1990): 16–20.

Golden Catherine. “Natural Companions: Text and Illustration in the Work of Beatrix Potter.” In Beatrix Potter as Writer and Illustrator.Beatrix Potter Studies VIII (1998): 50–68.

Golden, Catherine. Serials to Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2017.

Lane, Margaret. The Magic Years of Beatrix Potter. London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1978.

Lear, Linda. Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2008.

Linder, Leslie. A History of the Writings of Beatrix Potter. London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1979.

Linder, Leslie. The Journal of Beatrix Potter from 1881–1897. London: Frederick Warne and Co., Ltd., 1979.

Linder, Leslie, and Enid Linder. The Art of Beatrix Potter. London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1985.

Potter, Beatrix. The Tale of Benjamin Bunny. 1904. Illus. by the author. London: Penguin, 1989. Rept. 2002.

Potter, BeatrixThe Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher. 1906. Illus. by the author. London: Penguin, 1989.

Potter, Beatrix. The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle. 1905. Illus. by the author. London: Penguin, 1989.

Potter, Beatrix. The Tale of Peter Rabbit. 1902. Illus. by the author. London: Penguin, 1989. Rept. 2002.

Potter, Beatrix.The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin. 1903. Illus. by the author. London: Penguin, 1989.

Created 19 March 2017

Last modified 19 July 2022