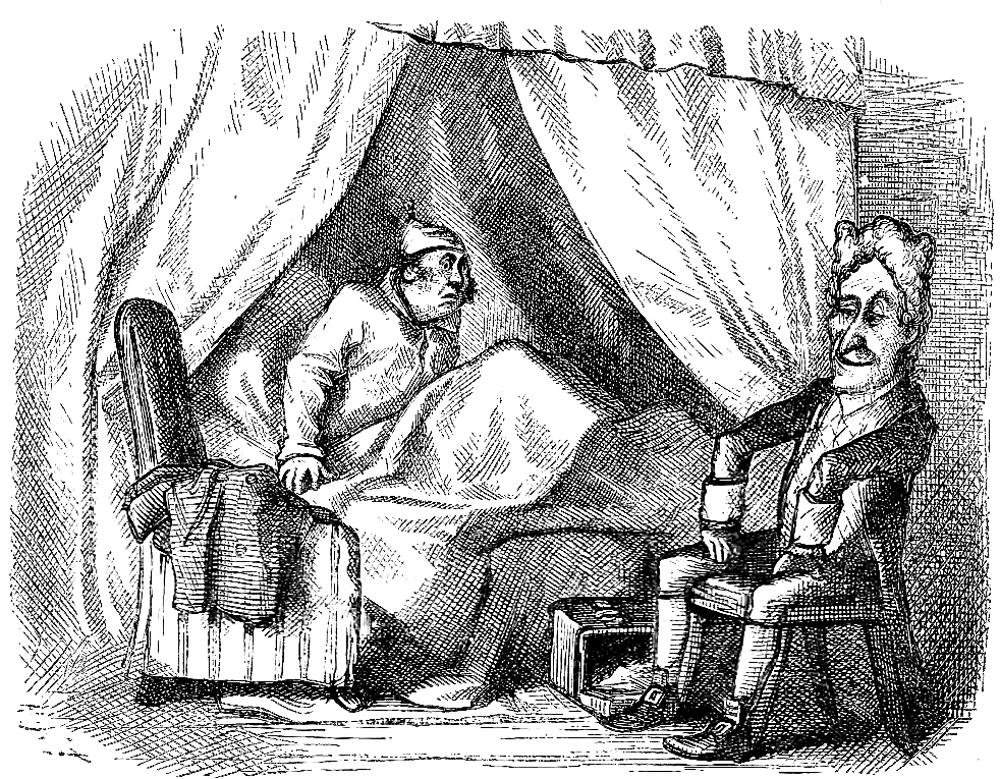

The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). Household Edition of Dickens's Pickwick Papers, p. 89. Engraved by one of the Dalziels. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary: A Facetiously Supernatural Tale Told by a Salesman

With a greater number of illustrations than the November 1837 volume, the Household Edition on both sides of the Atlantic presented the illustrators of The Pickwick Papers with the opportunity to provide realisations of moments in the interpolated tales, in addition to "The Goblin Who Stole the sexton," which Phiz animatedly illustrated in the initial, 1836-37 serial.

In the case of the seventh short story that Dickens wrote and published in 1836, the fourth interpolated tale of the novel, "The Bagman's Story" of travelling salesman Tom Smart and the talkative chair, both Hablot Knight Browne and Thomas Nast provided woodcuts in which the dreamer in his nightgown and nightcap, sitting up and apparently wide awake (despite the effects of half-a-dozen tumblers of punch after a ride through wind and rain) in an old inn on the Marlborough Downs converses with the elderly chair in his bedroom. The secret that the old chair imparts enables Tom to eliminate his rival for the hand of a wealthy, attractive widow who is the inn's kindly landlady.

What the improbable tale of the supernatural (told by the one-eyed bagman or travelling salesman in the commercial travellers' room at the Peacock Inn in Eatanswill) lacks in power and artistry it makes up for in the charm of description, enforcing the momentary reader's belief through highly specific descriptions of Tom Smart's gig, spirited mare, and dreary journey across the downs in a driving storm. Part of the anticipatory set which makes the story enjoyable is that, at its opening, the reader already knows the protagonist will encounter a talking chair because of the presence of an informative illustration — The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart by Phiz for British readers, and A most extraordinary change seemed to come over it by Nast for Americans. Thus, the Household Edition reader is prepared for the miraculous transformation in advance of encountering the scene in the text; in the American Household Edition, although the illustration occurs on the same page as the text, the reader processes the illustration prior to reading the passage, even if he or she can resist the overwhelming temptation to see what illustrations will occur within the chapter before he or she actually begins to read it. The behaviour and attitude of the talking chair enable the reader to suspend disbelief long enough to enjoy the poetic justice of the would-be bigamist's being discredited by the letter he has foolishly left in his trouser-pocket for Tom to discover — with the aid of the old chair — and deploy against him. Although both Nast and Phiz have elected to realise the same scene, there are some differences in their treatment, as Phiz makes the remarkable chair the centre of his picture, while Nast has chosen to focus on the protagonist instead by giving him greater prominence and showing him unobscured by bed curtains. The artists have also realised the magical chair with differing degrees of success, for Nast's chair is almost entirely an old man of eighteenth-century vintage (the setting being approximately 1750), while Phiz's is merely a chair with a face that renders Tom curious rather than, as in Nast's illustration, startled. Examining the passage and comparing its descriptions of the padded armchair, the reader with both illustrations before him may decide which more effectively realises Dickens's amusing and imaginative description of the "fairy godfather" figure:

"Tom gazed at the chair; and, suddenly as he looked at it, a most extraordinary change seemed to come over it. The carving of the back gradually assumed the lineaments and expression of an old, shrivelled human face; the damask cushion became an antique, flapped waistcoat; the round knobs grew into a couple of feet, encased in red cloth slippers; and the whole chair looked like a very ugly old man, of the previous century, with his arms akimbo. Tom sat up in bed, and rubbed his eyes to dispel the illusion. No. The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart. [Chapter 14: Harper & Bros. edition, p. 86; Chapman & Hall edition, p. 93]

In Phiz's version, light from the fireplace (left) plays across the room, highlighting Tom, sitting up in the four-poster, and leaving in partial darkness the chair with a face and the dresser (the "oaken press" that figures prominently in the hidden letter plot) with decorative goblins on either side that imply the object's numinous power. The chair, occupying the centre of the composition, looks towards the right register but is separated from Tom by the bed curtains, which take up an inordinate amount of space. In Nast's version, the orientation of the picture is completely reversed, with the dreamer on the left, and the chair on the right: Tom Smart, looking towards the right, occupies the centre of the composition, with a large stuffed chair to the left balancing the transformed chair to the right. On the whole, Nast seems not to have concerned himself with the fireplace as the available light source as the entire composition is well-lit (implying, perhaps, that the fireplace is in the "fourth wall," i. e., the viewer's position). Although Nast's figures are better modelled, his Tom is not the beguiled and attractive youth of Phiz's plate, but rather a middle-aged, slightly overweight bachelor sporting bushy sideburns. Despite the fact that Phiz's illustration lacks the intricate detailing of his earlier style, the British Household Edition plate is more successful (through Tom's expression and the oaken press) at communicating the tall tale's sense of the wondrous which Dickens termed "Fancy."

Related Material

- Thomas Nast's Illustrations the Household Edition (1873)

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Related Materials: Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-68

- Interpolated Tales in Dickens's Pickwick Papers

- A Comprehensive List of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-1868

- An Overview of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-1868

- A Critical Analysis of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-68

- Dickens' Aesthetic of the Short Story

- The Victorian Short Story: A Brief History

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Robert Seymour and Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall, 1836-37.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Patten, Robert L. "The Art of Pickwick's Interpolated Tales." ELH 34 (1967): 349-66.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 10 June 2019