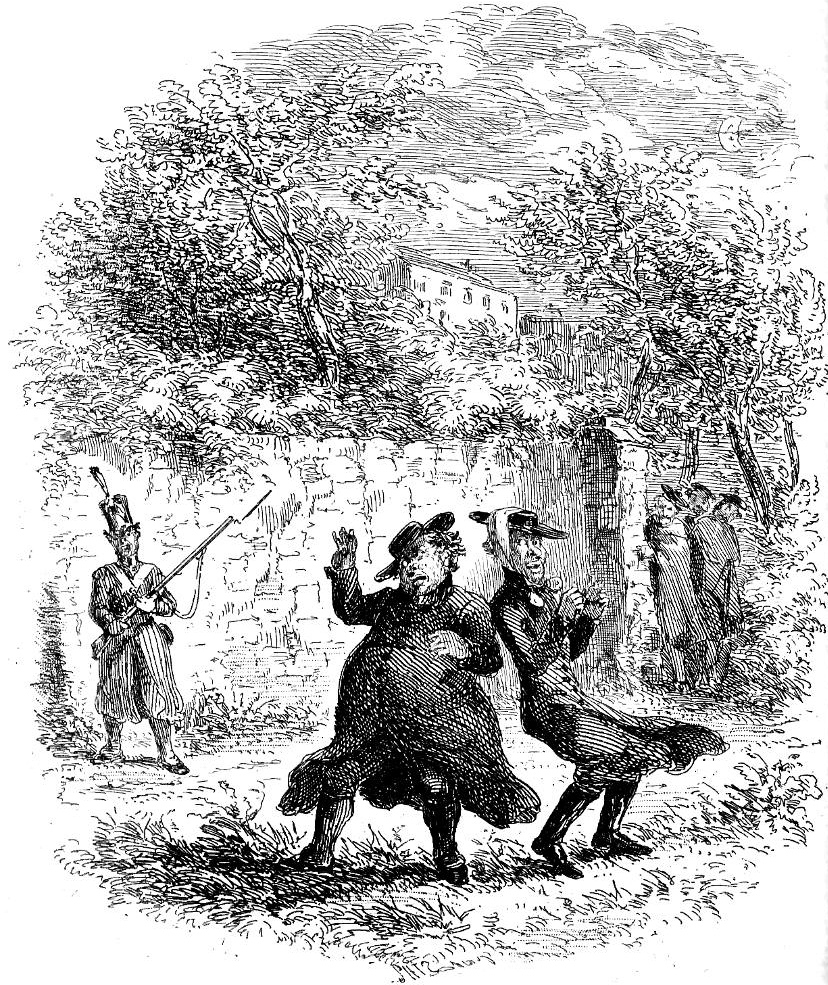

The Sentry challenging Father Luke and the Abbé.

Phiz

Dalziel

1839

Steel-engraving

12.2 cm high by 10.4 cm wide (4 ¾ by 4 ⅛ inches), facing p. 49, vignetted, in Chapter VI, "The Priest's Supper — Father Malachi and the Coadjutor — Major Jones and the Abbé."

Source: Confessions of Harry Lorrequer.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: A Little Orange Humour

They jogged on for a few minutes in silence, till they came to that part of the "Duke's" demesne wall, where the first sentry was stationed. By this time the officers, headed by the major, had quietly slipped out of the gate, and were following their steps at a convenient distance.

The fathers had stopped to consult together, what they should do in this trying emergency — when their whisper being overheard, the sentinel called out gruffly, in the genuine dialect of his country, "who goes that?"

"Father Luke Mooney, and the Abbé D'Array," said the former, in his most bland and insinuating tone of voice, a quality he most eminently possessed.

"Stand and give the countersign."

"We are coming from the mess, and going home to the college," said Father Mooney, evading the question, and gradually advancing as he spoke.

"Stand, or I'll shot ye," said the North Corkian.

Father Luke halted, while a muttered "Blessed Virgin" announced his state of fear and trepidation.

"D'Array, I say, what are we to do."

"The countersign," said the sentry, whose figure they could perceive in the dim distance of about thirty yards.

"Sure ye'll let us pass, my good lad, and ye'll have a friend in Father Luke the longest day ye live, and ye might have a worse in time of need; ye understand."

Whether he did understand or not, he certainly did not heed, for his only reply was the short click of his gun-lock, that bespeaks a preparation to fire.

"There's no help now," said Father Luke; "I see he's a haythen; and bad luck to the major, I say again;" and this in the fulness of his heart he uttered aloud.

"That's not the countersign," said the inexorable sentry, striking the butt end of the musket on the ground with a crash that smote terror into the hearts of the priests.

Mumble — mumble — "to the Pope," said Father Luke, pronouncing the last words distinctly, after the approved practice of a Dublin watchman, on being awoke from his dreams of row and riot by the last toll of the Post-office, and not knowing whether it has struck "twelve" or "three," sings out the word "o'clock," in a long sonorous drawl, that wakes every sleeping citizen, and yet tells nothing how "time speeds on his flight."

"Louder," said the sentry, in a voice of impatience.

_____ "to the Pope."

"I don't hear the first part."

"Oh then," said the priest, with a sigh that might have melted the heart of anything but a sentry, "Bloody end to the Pope; and may the saints in heaven forgive me for saying it."

"Again," called out the soldier; "and no muttering."

"Bloody end to the Pope," cried Father Luke in bitter desperation.

"Bloody end to the Pope," echoed the Abbé.

"Pass bloody end to the Pope, and good night," said the sentry, resuming his rounds, while a loud and uproarious peal of laughter behind, told the unlucky priests they were overheard by others, and that the story would be over the whole town in the morning. [Chapter VI, "The Priest's Supper — Father Malachi and the Coadjutor — Major Jones and the Abbé," 49]

Commentary

The problem with identifying the moment realised in this illustration is complicated by the fact that Lever describes Father Malachi Brenan's "Coadjutor" or curate at the very opening of Chapter VI, immediately after his description of the Herculean Father Malachi:

The very antipodes to the 'bonhomie' of this figure, confronted him as croupier at the foot of the table. This, as I afterwards learned, was no less a person than Mister Donovan, the coadjutor or "curate;" he was a tall, spare, ungainly looking man of about five and thirty, with a pale, ascetic countenance, the only readable expression of which vibrated between low suspicion and intense vulgarity: over his low, projecting forehead hung down a mass of straight red hair; indeed — for nature is not a politician — it almost approached an orange hue. [Chapter VI, "The Priest's Supper — Father Malachi and the Coadjutor — Major Jones and the Abbé," 49]

Since the curate in the plate is "spare" and "ungainly," the reader concludes that this must be the cartoon-like figure to the right. In fact, the rich brogue of the narrator, his Irish dialect, and his occasional use of Latin and Erse, all betray the fact that the narrator of the passage associated with The Sentry challenging Father Luke and the Abbé is not Lorrequer, but Father Malachi himself. The fat priest in the engraving is therefore Father Luke, and the Stan Laurel figure is Abbé D'Array. The Frenchman has used a scarf to tie his hat upon his head, and turns away from the wind, which is vigorously blowing his clerical gown to the right. The eye of the viewer thus moves from challenging sentry left, pointing his musket and bayonet at the portly Mooney, through the Abbé, to those shadowy figures in hiding (right rear). By the time that the clerical duo have arrived at the Duke's demesne wall in the background, and have encountered the sentry, the Major and his fellow officers ("confederates") have stationed themselves within earshot but more or less out of sight. These Protestant officers, observing and overhearing the priests' uttering the anti-Catholic watchword, are the visual key to decoding to what amounts to the realisation of "red-hot Orangeman" Major John Jones's practical joke on the easily duped priests. The foregrounded figures of the two priests show that Phiz cannot resist exploiting the visual humour of the stereotypical comedic duo, the pasty-faced, thin aesthete and his corpulent companion, Father Luke Mooney, who are habitual freeloaders at the officers' mess.

Companion Plate for This Chapter

Bibliography

Buchanan-Brown, John. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978.

Lester, Valerie Browne Lester. Phiz! The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablot Knight Browne]. Dublin: William Curry, Jun. London: W. S. Orr, 1839.

Steig, Michael. Chapter Two: "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-85.

Steig, Michael. Chapter Seven: "Phiz the Illustrator: An Overview and a Summing Up." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 299-316.

Stevenson, Lionel. Chapter V, "Renegade from Physic, 1839-1841." Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. London: Chapman and Hall, 1939. Pp. 73-93.

_______. "The Domestic Scene." The English Novel: A Panorama. Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin and Riverside, 1960.

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Harry

Lorrequer

Next

13 April 2023