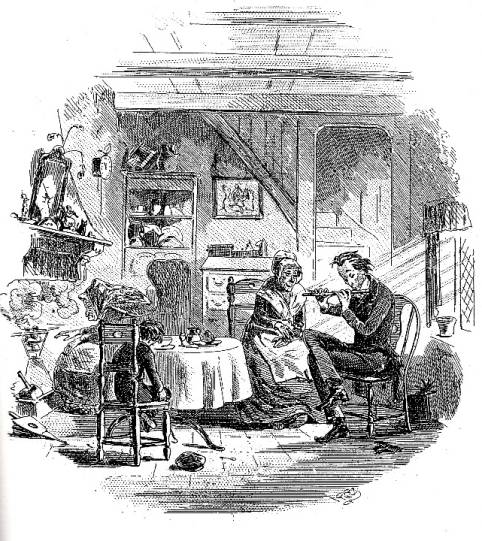

"My Musical Breakfast"

Phiz (Halbot K. Browne)

June 1849

Etching

Dickens's David Copperfield, ch. 5, "I Am Sent Away from Home."

Source: Centenary Edition, facing page 90.

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Phiz —> Illustrations of David Copperfield —> Next]

"My Musical Breakfast"

Phiz (Halbot K. Browne)

June 1849

Etching

Dickens's David Copperfield, ch. 5, "I Am Sent Away from Home."

Source: Centenary Edition, facing page 90.

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Second June 1849 illustration for Charles Dickens's David Copperfield. Steel etching. Source: Centenary Edition (1911), volume one, facing page 90. All forty Phiz plates were etched in duplicate, as was the case with Dombey and Son, the duplicates differing only slightly from the originals. Phiz contributed forty etchings and the "lie of every man" wrapper design. Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

The second illustration for the second monthly number, containing chapters 4, 5, and 6, again realizes a moment from the fifth chapter. Again, (as in all the previous plates featuring the child-protagonist) David is seated as he observes an apparently benevolent adult male— however, as Dickens continues to explore the limitations of the child's retrospective point of view, unlike the "Friendly Waiter" of the previous illustration, the Salem House master, Mr. Mell, is sincere in his ministrations. As in the letterpress accompanying the initial illustration, "Our Pew at Church," David is drowsing, thereby escaping his present circumstances. The boy, having arrived in London by coach, has been met by Mr. Mell, one of the masters at his new school, Salem House [Dickens's own Wellington House Academy, thinly disguised], who takes the boy for breakfast at his mother's. The illustration captures the moment when, after preparing and serving the boy a generous breakfast, Mrs. Mell requests that her son play his instrument:

"Have you got your flute with you?"

"Yes," he returned.

"Have a blow at it," said the old woman, coaxingly. "Do!"

The Master, upon this, put his hand underneath the skirts of his coat, and brought out his flute in three pieces, which he screwed together, and began immediately to play. My irnpression is, after many years of consideration, that there never can have been anybody in the world who played worse. He made the most dismal sounds I have ever heard produced by any means, natural or artificial. I don't know what the tunes were—if there were such things in the performance at all, which I doubt—but the influence of the strain upon me was, first, to make me think of alI my sorrows until I could hardly keep my tears back; then to take away my appetite; and lastly, to make me so sleepy that I couldn't keep my eyes open. They begin to close again, and I begin to nod, as the recollection rises fresh upon me. Once more the little room, with its open corner cupboard, and its square-backed chairs, and its angular little staircase leading to the room above, and its three peacock's feathers displayed over the mantelpiece—I remember wondering when I first went in what that peacock would have thought if he had known what his finery was doomed to come to— fades from before me, and I nod, and sleep. The flute becomes inaudible, the wheels of the coach are heard instead, and I am on my journey. The coach jolts, I wake [90/91] with a start, and the flute has come back again, and the Master at Salem House is sitting with his legs crossed, playing it dolefully, while the old woman of the house looks on delighted. She fades in her turn, and he fades, and all fades, and there is no flute, no Master, no Salem House, no David Copperfield, no anything but heavy sleep. [ch. 5, "I am sent away from home"]

Phiz has had no difficulty in capturing every textual detail of the scene, including the curmudgeonly elder, Mrs. Fibbitson, a pile of rags warming herself before the fire, and has even extended the letterpress in conveying Mrs. Mell's obvious delight with her son's playing and pride in his having become a school master. However, the illustrator cannot convey the decrepit senior's "unmelodious laugh" (90) or her antipathy towards the child who has suddenly seized her companion's attention. But, most of all, Phiz has been unable to capture the effect of the shift in tense from perfect to present, through which the writer signals the shift from the real to the dream world of the young narrator. The sunny, cheerful little room is hardly how one might imagine a paper's residence, one of a series of alms-houses that David has learned by reading the inscription above the arch have been established for twenty-five "poor women." Little does the viewer-reader realize at this point that being in possession of this knowledge of Mr. Mell's personal background will precipitate the crisis depicted in the ensuing illustration.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield, il. Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. London and New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co. [1904].

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana U. P., 1973.

Last modified 15 November 2009