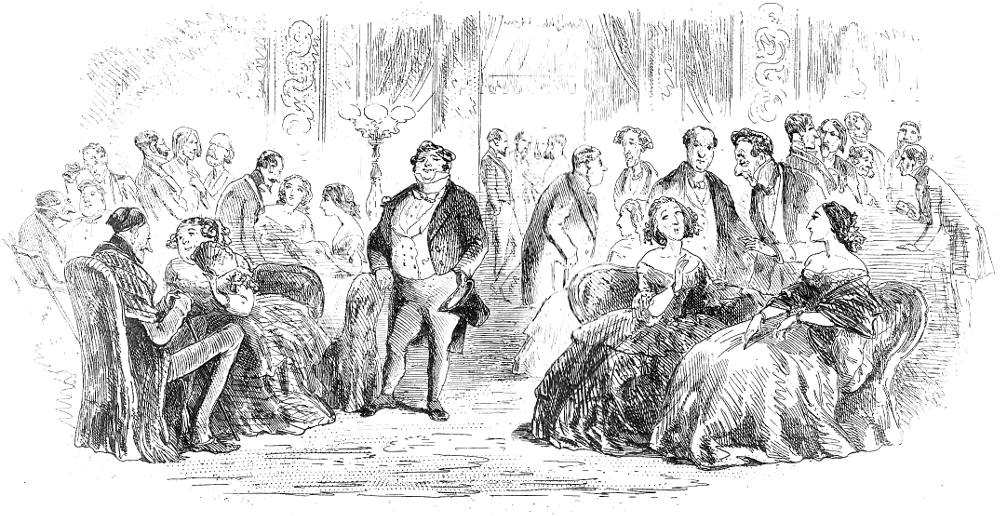

Votaries of Hydropathy by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), fourth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Part 2 (August 1857), Chapter 7, "An Arrival at Midnight," facing page 59. Steel-plate etching, 3 ½ by 7 inches (8.6 cm high by 17.9 cm wide), vignetted.

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Passage Illustrated: Reverting to the High Society of the Villa d'Este

The Villa d'Este was a-glitter with light. The great saloon which opened on the water blazed with lamps; the terraces were illuminated with many-colored lanterns; solitary candles glimmered from the windows of many a lonely chamber; and even through the dark copses and leafy parterres some lamp twinkled, to show the path to those who preferred the scented night air to the crowded and brilliant assemblage within doors. The votaries of hydropathy are rarely victims of grave malady. They are generally either the exhausted sons and daughters of fashionable dissipation, the worn-out denizens of great cities, or the tired slaves of exciting professions, — the men of politics, of literature, or of law. To such as these, a life of easy indolence, the absence of all constraint, the freedom which comes of mixing with a society where not one face is known to them, are the chief charms; and, with that, the privilege of condescending to amusements and intimacies of which, in their more regular course of life, they had not even stooped to partake. To English people this latter element was no inconsiderable feature of pleasure. Strictly defined as all the ranks of society are in their own country, — marshalled in classes so rigidly that none may move out of the place to which birth has assigned him, — they feel a certain expansion in this novel liberty, perhaps the one sole new sensation of which their natures are susceptible. It was in the enjoyment of this freedom that a considerable party were now assembled in the great saloons of the villa. There were Russians and Austrians of high rank, conspicuous for their quiet and stately courtesy; a noisy Frenchman or two; a few pale, thoughtful-looking Italians, men whose noble foreheads seem to promise so much, but whose actual lives appear to evidence so little; a crowd of Americans, as distinctive and as marked as though theirs had been a nationality stamped with centuries of transmission; and, lastly, there were the English, already presented to our reader in an early chapter, — Lady Lackington and her friend Lady Grace, — having, in a caprice of a moment, descended to see "what the whole thing was like."

"No presentations, my Lord, none whatever," said Lady Lackington, as she arranged the folds of her dress, on assuming a very distinguished position in the room. "We have only come for a few minutes, and don't mean to make acquaintances."

"Who is the little pale woman with the turquoise ornaments?" asked Lady Grace.

"The Princess Labanoff," said his Lordship, blandly bowing.

"Not she who was suspected of having poisoned —"

"The same."

"I should like to know her. And the man, — who is that tall, dark man, with the high forehead?"

"Glumthal, the great Frankfort millionnaire."

"Oh, present him, by all means. Let us have him here," said Lady Lackington, eagerly. "What does that little man mean by smirking in that fashion, — who is he?" asked she, as Mr. O'Reilly passed and repassed before her, making some horrible grimaces that he intended to have represented as fascinations.

"On no account, my Lord," said Lady Lackington, as though replying to a look of entreaty from his Lordship.

"But you'd really be amused," said he, smiling. "It is about the best bit of low comedy —"

"I detest low comedy." [Chapter VII, "An Arrival at Midnight," pp. 58-59]

Commentary: Dunn Arrives at Como

Russians and Austrians of high rank, conspicuous for their quiet and stately courtesy; a noisy Frenchman or two; a few pale, thoughtful-looking Italians, men whose noble foreheads seem to promise so much, but whose actual lives appear to evidence so little; a crowd of Americans, as distinctive and as marked as though theirs had been a nationality stamped with centuries of transmission; and, lastly, there were the English, already presented to our reader in an early chapter, — Lady Lackington and her friend Lady Grace, — having, in a caprice of a moment, descended to see "what the whole thing was like." — Chapter VII, "An Arrival at Midnight," p. 64.

Phiz has attempted to convey a sense of the commonality between these upper-class "votaries of hydropathy," namely the affluence and sophistication of the multi-national gathering. In fact, in the illustration, only a few figures stand out: the English aristocratic ladies to the right; the invalid to the left, and the large, barrel-chested, fashionably dressed man of indeterminate nationality in the centre, who is more likely the Frankfurt banker, Baron von Glumthal; than the poker-playing Honourable Leonidas Shinbone (with such a mixed name, an American, of course); Dr. Lanfranchi, the maser of ceremonies; or Lord Lackington (who, along with Twining, stands behind the ladies seated at the right). Among the male figures the reader of this second serial instalment, moreover, expects to meet the eponymous character in both the letterpress and the illustrations. Although Phiz does not include Davenport Dunn among the "votaries" assembled earlier in the evening, Lever describes the mysterious midnight visitor who has arrived in a grand equipage as follows:

The traveller, however, paid little attention to the Catalogue, but with the aid of the courier on one side and his-valet on the other, slowly descended from the carriage. If he availed himself of their assistance, there was little in his appearance that seemed to warrant its necessity. He was a large, powerfully built man, something beyond the prime of life, but whose build announced considerable vigor. Slightly stooped in the shoulders, the defect seemed to add to the fixity of his look, for the head was thus thrown more forward, and the expression of the deep-set eyes, overshadowed by shaggy gray eyebrows, rendered more piercing and direct His features were massive and regular, their character that of solemnity and gravity; and as he removed his cap, he displayed a high, bold forehead with what phrenologists would have called an extravagant development of the organs of locality. Indeed, these overhanging masses almost imparted an air of retreating to a head that was singularly straight. [68]

Dunn, moreover, does not enter the Grand Salon, but mounts the stairs, and advances directly to the balcony of his apartments overlooking the lake. He agrees to see Glumthal at once, but inexplicably refuses to see Lackington until the noon on the coming day. The next chapter's title, "Mr. Dunn," promises the reader more than a mere nocturnal glimpse of the financial wizard, who, nevertheless, makes no appearance for the initial September illustration for the instalment, The Rehearsal, in which O'Reilly, Twining, and Molly O'Reilly consult Viscount Lackington in a garden pavilion at the Como estate the next day.

Reference

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Last modified 13 July 2019