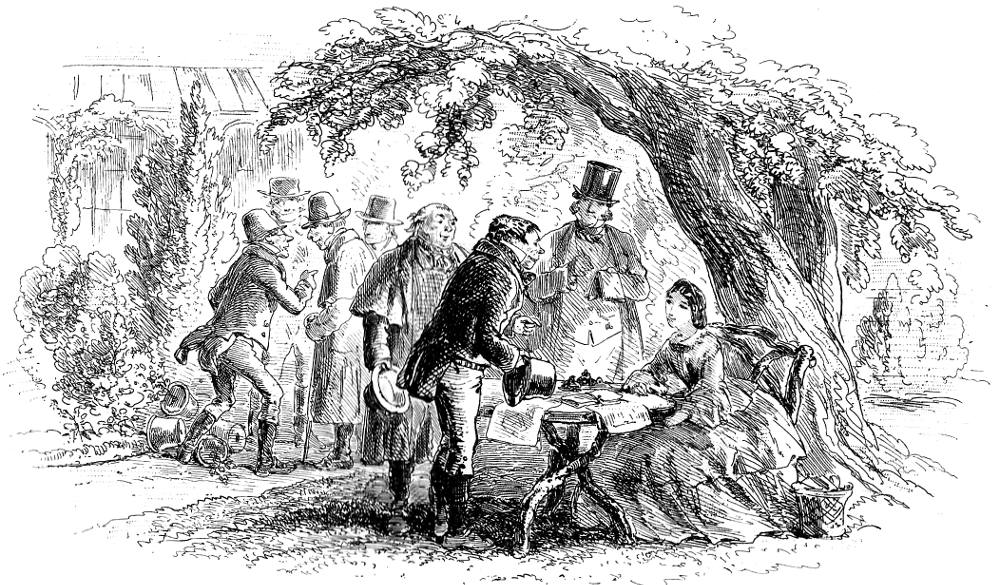

Miss Bella's Court (September 1858) by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), twenty-ninth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Part 15 (September 1858), Chapter LVII, "Some Days at Glengariff," facing 472.

Bibliographical Note

This appeared as the twenty-ninth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Steel-plate etching; 3 ¾ by 6 ½ inches (9.5 cm high by 16.3 cm wide), vignetted. The story was serialised by Chapman and Hall in monthly parts, from July 1857 through April 1859. The thirty-first and thirty-second illustrations in the volume initially appeared in the same order at the very beginning of the fifteenth monthly instalment, which went on sale on 1 September 1858. This number included Chapters LV through LVII, and ran from page 449 through 480 to make up the 32-page instalment. This pair of illustrations served to contrast Bella's business acumen in Ireland with Conway's military prowess in the Crimea.

Passage Illustrated: Bella Kellett comes into her own

Now, Sybella Kellett fancied that justice had a twofold obligation, and found herself very often the advocate of the poor man, patiently sustaining his rights, and demanding their recognition. Confidence, we are told by a great authority, is a plant of slow growth, and yet she acquired it in the end. The peasantry submitted to her claims the most complex and involved; they brought their quaint old contracts, half illegible by time and neglect; they recited, and confirmed by oral testimony, the strangest possible of tenures; they recounted long narratives of how they succeeded to this holding, and what claims they could prefer to that; histories that would have worn out almost any human patience to hear, and especially trying to one whose apprehension was of the quickest. And yet she would listen to the very end, make herself master of the case, and give it a deep and full consideration. This done, she decided; and to that decision none ever objected. Whatever her decree, it was accepted as just and fair, and even if a single disappointed or discontented suitor could have been found, he would have shrunk from avowing himself the opponent of public opinion.

It was, however, by the magic of her sympathy, by the secret charm of understanding their natures, and participating in every joy and sorrow of their hearts, that she gained her true ascendancy over them. There was nothing feigned or factitious in her feeling for them; it was not begotten of that courtly tact which knows names by heart, remembers little family traits, and treasures up an anecdote; it was true, heart-felt, honest interest in their welfare. She had watched them long and closely; she knew that the least amiable trait in their natures was also that which oftenest marred their fortunes, — distrust; and she set herself vigorously to work to uproot this vile, pernicious weed, the most noxious that ever poisoned the soil of a human heart. By her own truthful dealings with them she inspired truth, by her fairness she exacted fairness, and by the straightforward honesty of her words and actions they grew to learn how far easier and pleasanter could be the business of life where none sought to overreach his neighbor.

To such an extent had her influence spread that it became at last well-nigh impossible to conclude any bargain for land without her co-operation. Unless her award had decided, the peasant could not bring himself to believe that his claim had met a just or equitable consideration; but whatever Miss Bella decreed was final and irrevocable. From an early hour each morning the suitors to her court began to arrive. Under a large damson-tree was placed a table, at which she sat, busily writing away, and listening all the while to their long-drawn-out narratives. It was her rule never to engage in any purchase when she had not herself made a visit to the spot in question, ascertained in person all its advantages and disadvantages, and speculated how far its future value should influence its present price. In this way she had travelled far and near over the surrounding country, visiting localities the wildest and least known, and venturing into districts where a timid traveller had not dared to set foot. It required all her especial acuteness, often-times, to find out — from garbled and incoherent descriptions — the strange To such an extent had her influence spread that it became at last well-nigh impossible to conclude any bargain for land without her co-operation. Unless her award had decided, the peasant could not bring himself to believe that his claim had met a just or equitable consideration; but whatever Miss Bella decreed was final and irrevocable. From an early hour each morning the suitors to her court began to arrive. Under a large damson-tree was placed a table, at which she sat, busily writing away, and listening all the while to their long-drawn-out narratives. It was her rule never to engage in any purchase when she had not herself made a visit to the spot in question, ascertained in person all its advantages and disadvantages, and speculated how far its future value should influence its present price. In this way she had travelled far and near over the surrounding country, visiting localities the wildest and least known, and venturing into districts where a timid traveller had not dared to set foot. It required all her especial acuteness, often-times, to find out — from garbled and incoherent descriptions — the strange and out-of-the-way places no map had ever indicated. In fact, the wild and untravelled country was pathless as a sea, and nothing short of her ready-witted tact had been able to navigate it.

She was, as usual, busied one morning with her peasant levee when Mr. Hankes arrived. He brought a number of letters from the post, and was full of the importance so natural to him who has the earliest intelligence. [Chapter LVII, "Some Days at Glengariff," pp. 472-473]

Commentary: Dunn's Promotional Scheme Bears Fruit at Glengariff

Lever has set an important scene in this garden already, in the May instalment: The Despatch, in which Dunn receives word that a run is about to made at the Orrory Bank at Kilkenny. In that earlier scene, Sybella Kellett played the subsidiary role of messenger; now, she plays the central role, occupying the garden-seat at the base of the venerable damson tree. Otherwise, however, the scene reflects the transformation that Dunn's economic advice and assistance have wrought upon Glengariff, including the welfare of the peasantry, six of whom have come to conduct business with the noble family's retainer, attended by Dunn's confidential agent, Hankes. Land values have soared, and everybody in the neighbourhood is prospering thanks to the promotional campaign of "The Grand Glengariff Villa Allotment and Marine Residence Company." Rumour has it that Queen Victoria has purchased the Hermitage, whichshe intends to have utterly revamped in a Swiss-Bavarian style as the "Royal Cot." Perhaps the greenhouse in the background and the fashionable clothing of the peasant negotiating with Sybella suggest this general economic advance, which, as Lever initially mentions, has taken a toll on the unspoiled natural environment.

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, September 1858 (Part XV).

Last modified 9 April 2019