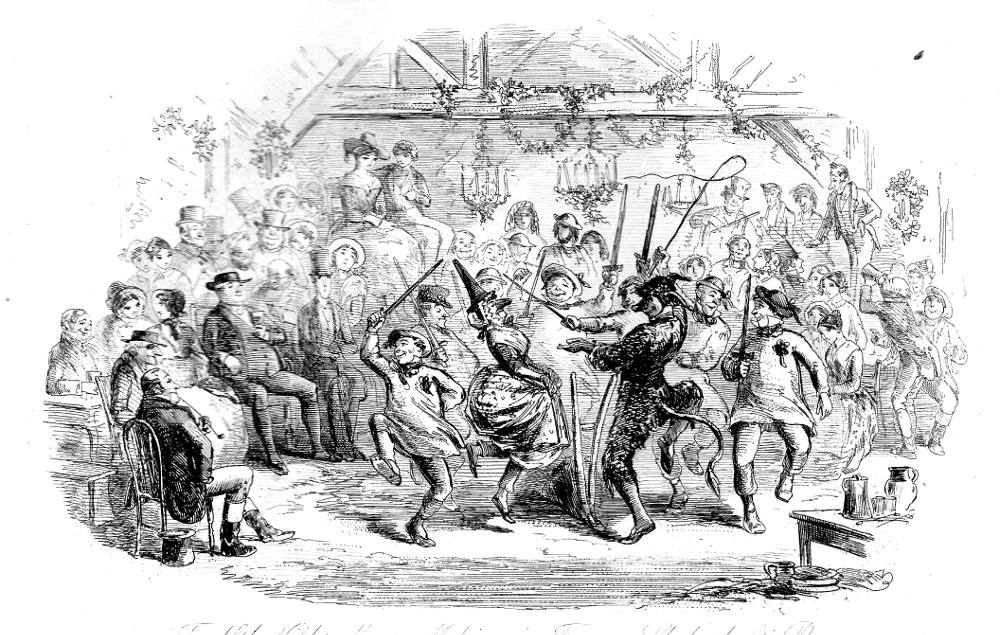

Twelfth Night Merry-making in Farmer Shakeshaft's Barn by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), fourth serial illustration for William Harrison Ainsworth's Life and Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe, Part 2 (January 1852), Chapter VI, "In which I ride round Marston Mere; meet with some Gipsies in a strange place; and take part at the Twelfth-Night merry-making in Farmer Shakeshaft's Barn." [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them.]

Bibliographical Note

The illustration in both the original Chapman and Hall serial and the later Routledge volume was a steel etching, 10.5 cm high by 16.5 cm wide, facing page 54 in the volume. Source: Ainsworth's Works (1882), originally published in the second serial instalment by Chapman and Hall in January 1852. This instalment originally comprised Book the First, Chapters 5, 6, 7, and 8.

.Passage Illustrated: The Twelfth-Night Festivities before the Drama with Malpas

Ned and Chetham now disappeared to prepare for the Plough Dance.

After partaking of some refreshments, of which, after our violent exercise, we stood in need, our master of the ceremonies, Simon Pownall, now called out to us to make way for the Fool Plough; whereupon the whole of the company drew up in lines, and the barn-doors being thrown wide open, a dozen men entered, clothed in clean white wollen shirts, ornamented with ribands, tied in roses, on the sleeve aud breast, and with caps decked with tinsel on their heads and tin swords by their sides. These mummers were yoked to a plough, likewise decked with ribands, which they dragged into the middle of the barn. They were attended by an old woman with a tall sugar-loaf hat, and an immense nose and chin, like those of Mother Goose in the pantomime. The old beldame supported her apparently tottering limbs with a crutch-handled staff, with which she dealt blows, right and left, hitting the toes of the spectators, and poking their ribs. This character was sustained by Chetham Quick, and very well he played it, to judge by the shouts of laughter he elicited. By the side of old Bessie was an equally grotesque figure, clothed in a dress partly composed of a cow's hide, and partly of the skins of various animals, with a long tail dangling behind, and a fox-skin cap, with lappets, on the head. This was the Fool. Over his shoulder he carried a ploughman's whip, with which he urged on the team, and a cow's horn served him for a bugle, from which he ever and anon produced unearthly sounds. Notwithstanding the disguise, there was no difficulty in recognising Ned Culcheth as the wearer of it. The entrance of the mummers was welcomed by shouts of laughter from the while assemblage, and the hilarious plaudits increased as they drew up in the middle of the barn, and unyoking themselves from the plough, prepared for the dance. The spectators then formed a ring round them. Chairs, on an elevated position, had been provided for Sissy and myself, who, as king and queen, were entitled to superior accommodation, and we therefore looked on at our ease. The musicians now struck up a lively air, and the dance began, the mummers first forming two lines, then advancing towards each other, rattling their swords together, as if in mimic warfare; retreating; advancing again, and placing all their points upon the plough, dancing very funnily by themselves. A general clapping of hands show how well this dance was liked by the company, and the mummers were brought by Simon Pownall to be presented to the king and queen. [Book One, Chapter VI, "In which I ride round Marston Mere; meet with some Gipsies in a strange place; and take part at the Twelfth-Night merry-making in Farmer Shakeshaft's Barn," p. 53-54]

Commentary: A Contrasting Comic Scene in the January 1852 Instalment

To contrast the suspenseful scene earlier in the January 1852 instalment, in which the ruffianly Phaleg menaces the protagonist, Phiz provides an interior scene of the community at festival. He provides a civilsed alternative to The picturesque scene set in a weird glenn occupied by outlandish figures. The figure of Mervyn Clitheroe provides visual continuity, although once again he is not a the centre of the composition, but is relegated to the sidelines. Although Mervyn's arch-rival, Malpas Sale (seated to the left, beside his parents in the illustration), causes a scene shortly after the moment realised when he attacks Simon Pownall for having given the King's piece of Twelfth Cake to Mervyn, Malpas in his top hat looks perfectly innocuous in Phiz's illustration.

As the King of the festivities, a position that his nemesis, Malpas Sale, had coveted, Mervyn and the Twelfth Night Queen, Sissy, Ned Culcheth's young and highly attractive Welsh wife, are seated above the dancing floor as the mummers take centre stage. Eight "worthies," wealthy bourgeois residents of the rural county, are seated on the earthen floor immediately in front of the dancers; we may infer that the husband and wife seated in the centre of this group are the Reverend Dr. and Mrs. Sale, Malpas's parents, and that beside them wearing his usual eyepatch is Mervyn's rich but eccentric Uncle Mobberley, featured in the previous month's illustration Who Shot the Cat?.

Ainsworth may have derived the notion of having the ebullient Master of Ceremonies, Simon Pownall, vigorously cutting capers from the scene in Fezziwig's warehouse in Stave Two of A Christmas Carol (December 1843), but Dickens merely mentions the unseen Scrooge's attending a children's Twelfth-Night party in passing as he and the Spirit of Christmas Present move through the streets of London, whereas Ainsworth paints a detailed picture of the markedly rural and traditional celebration which emphasized the random selection of a lord and lady to preside over the evening's dancing and mumming:

"Now, now, the mirth comes, With the cake full of plums, Where BEAN is King of the sport here. Beside, you must know, The PEA also Must revel as Queen of the court here." [52]

In the second instalment of the novel, issued in early January, 1852, Ainsworth's protagonist-narrator receives the title of King of Twelfth Night because he (rather than his rival, Malpas Sale) has received the piece of the Twelfth cake containing the bean; Ned Culchethh's pretty wife, Sissy, becomes Queen when he receives the piece containing the pea. Ainsworth describes them as enthroned on an upper bench as they preside over the mummers' dance around the "Fool Plough," bedecked with ribbons. The twelve outlandishly dressed dancers, wielding tin swords, perform an exuberant, grotesque folk-dance named "Old Bessie." Phiz makes the Mother Goose figure with hideous features (played by a man) and the Fool (Simon Pownall dressed in animal skins with a fool's hat and a cow's tail) the focal point of the dance.

Although Anisworth specifies that there are a dozen mummers, Phiz depicts just ten. Otherwise, however, so thorough has Phiz been in his realization of the text that he has included the ruffianly Gipsy, Phaleg, in the background, centre — rather far away from the action in which he is about to intervene. The young man in the distinctive top hat, seated beside the Reverend and Mrs. Sale, left of the dancers, must be their son, Malpas, since this figure corresponds to that of the antagonist in the upper-left-hand corner of the previous illustration. He does not seem to be under the influence of either alcohol or jealousy, so that the illustration does not prepare us for his jumping on the back of the Fool and assaulting him in front of so many merry-making witnesses. Retaliating against the Fool (Ned) for giving the King's piece of Twelfth Cake to Mervyn rather than himself, a "furious" Malpas throws him on the ground and is assisted by Phaleg, who holds Ned down as Malpas places his foot on the neck of the prostrate Fool. In no way, then, does Phiz prepare the reader for this violent action about to erupt in the text.

The Twelfth Cake and Twelfth Night Observances

A rather ornate Twelfth Cake appeared in the Illustrated London News on 13 January 1849. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Christmas 1848 and Twelfth Night 1849 participated in the old Christmas rituals and entertainments that had fallen into disuse until revived in the 1840s and strengthened by the introduction from Germany of the Christmas tree, the innovation of the Christmas card, and the publication of the literary masterpiece A Christmas Carol as the first "Christmas Book." This large pastry (not actually a cake) of flour, honey, ginger, and pepper would have a bean or coin baked inside: whoever received the slice with the prize would become 'king' or 'queen' of the seasonal celebration of the Feast of the Epiphany (January 6th), a custom dating back to at least Elizabethan times. Thomas Hardy provided sketches of the costumes of the seasonal mummers for Arthur Hopkins' illustration of the mumming scene from the original serialisation of Hardy's The Return of the Native, "If there is any difference, Grandfer is younger" from the May 1878 number of Belgravia. Whereas Dickens integrates such customs of the Christmas dance and the Twelfth Night party into a modern, urban context, Ainsworth takes his readers back to the opening of the nineteenth century and the countryside outside Manchester (Cottonborough), just as Hardy in The Return of the Native (1878) sets the mumming scene back a generation, to rural Dorset (Wessex) in the 1840s.

Relevant Seasonal Illustrations, 1843-49

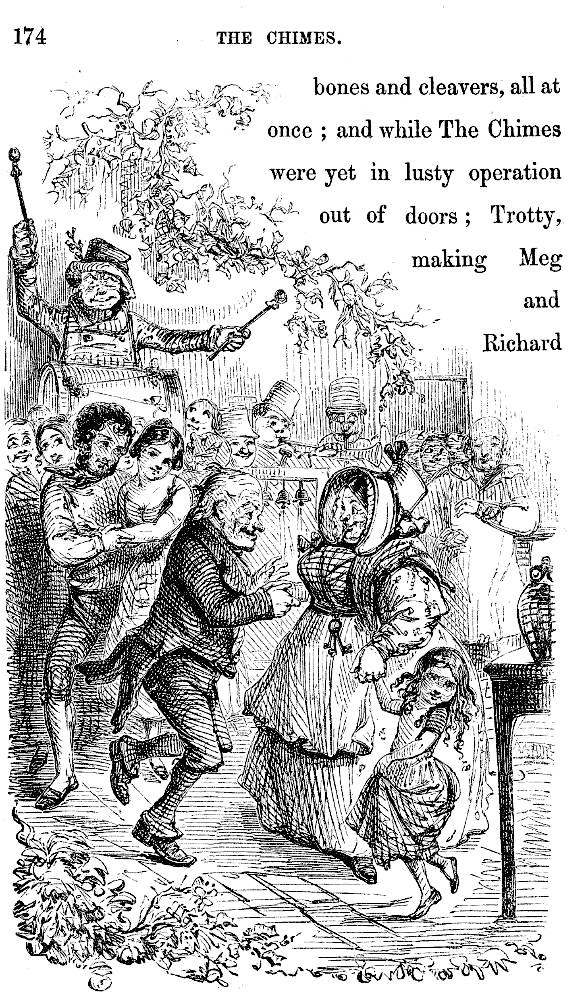

Left: The original John Leech engraving which influenced so many later illustrators, Fezziwig's Ball (December 1843). Centre: John Leech's concluding illustration for The Chimes, The New Year's Dance (December 1844). Right: The Illustrated London News illustration of the royal family's seasonal plum cake, The Queen's Twelfth Cake (13 January 1849).

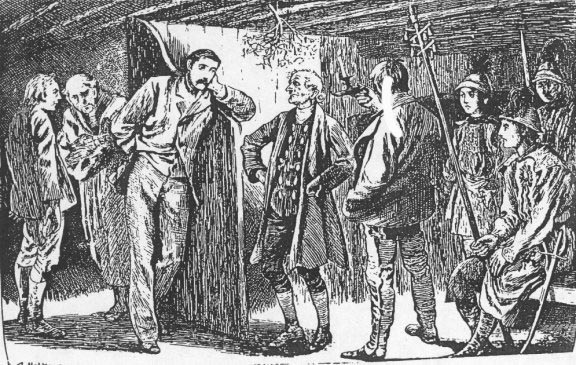

Above: Arthur Hopkins' interpretation of the mumming scene as Thomas Hardy originally published it in the monthly serialisation of The Return of the Native, "If there is any difference, Grandfer is younger" from the May 1878 number of Belgravia.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Life and Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe (1851-2; 1858). Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Routledge, 1882.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Vann, J. Don. "William Harrison Ainsworth. Mervyn Clitheroe, twelve parts in eleven monthly installments, December 1851-March 1852, December 1857-June 1858." New York: MLA, 1985. 27-28

Created 23 November 2018

Last modified 17 March 2021