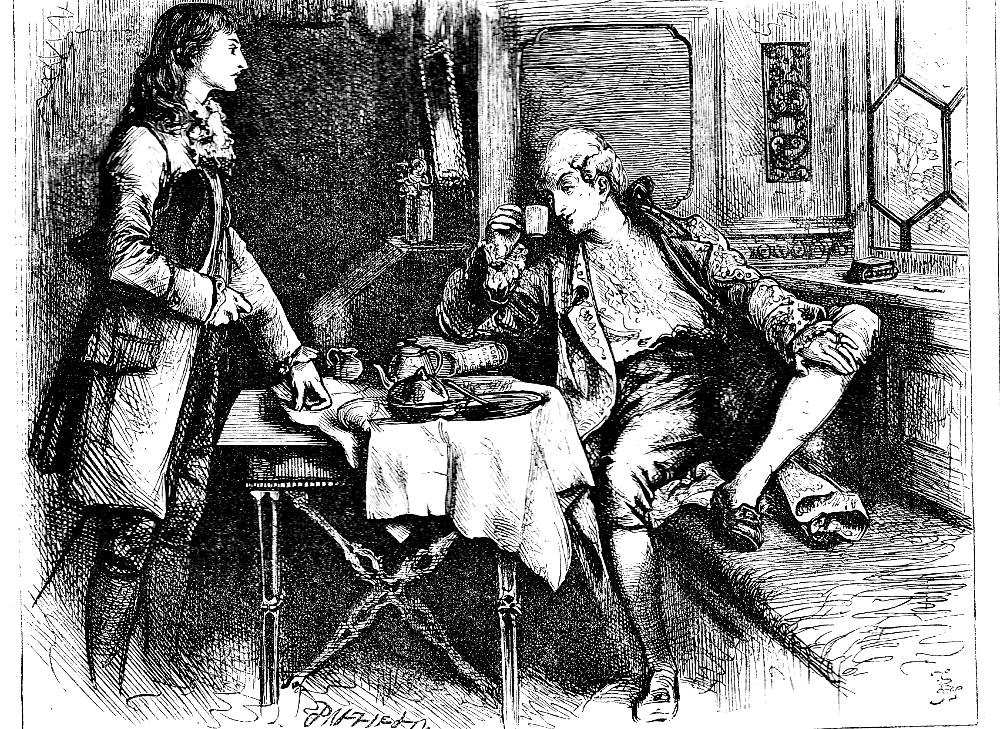

Mr. Chester Takes his Ease at his Inn — sixteenth illustration in the series. Twelfth regular plate by Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz). Chap. XV (10 April 1841: serial instalment 9), Vol. III, 14. Wood engraving, 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ inches (8.2 cm high by x 11 cm wide), vignetted. Volume Three, Part 52 of Master Humphrey's Clock, in which Dickens's Barnaby Rudge originally appeared. The 1849 Bradbury and Evans two-volume edition: middle of 14, framed by the text realised. Running Head: "Master Humphrey's Clock" (14). [Click on the images in order to enlarge them.]

Context of the Illustration: Mr. Chester's Toothpick

"Ned is amazingly patient!" said Mr. Chester, glancing at this last-named person as he set down his teacup and plied the golden toothpick, "immensely patient! He was sitting yonder when I began to dress, and has scarcely changed his posture since. A most eccentric dog!"

As he spoke, the figure rose, and came towards him with a rapid pace.

"Really, as if he had heard me," said the father, resuming his newspaper with a yawn. "Dear Ned!"

Presently the room-door opened, and the young man entered; to whom his father gently waved his hand, and smiled.

"Are you at leisure for a little conversation, sir?" said Edward.

"Surely, Ned. I am always at leisure. You know my constitution. — Have you breakfasted?"

"Three hours ago."

"What a very early dog!" cried his father, contemplating him from behind the toothpick, with a languid smile. [Vol. III, Chapter the Fifteenth, 14]

Commentary: Not "At an Inn," but "In The Temple" — The Paper Buildings

The title comes from Hammerton (1910). None of the plates in Master Humphrey's Clock is captioned, so that the traditional titles for the plates in both novels may be traced by to this early modern critic. But in this instance Hammerton has erred in the title he has assigned because "John Willet's guest" (13) is no longer at Chigwell; rather, he has returned to his rooms at The Temple, overlooking the Thames, and is enjoying a leisurely breakfast. His son, Ned, who left Chigwell the night before rather than confront his meddling parent at the Maypole, now interupts Mr. Chester, stretched out comfortably on his cushioned window-seat as he picks his teeth with the object that so well represents his attitude towards life: a golden toothpick. The physical setting should have been obvious enough to Harry Furniss's editor:

The situation in which he found himself, indeed, was particularly favourable to the growth of these feelings; for, not to mention the lazy influence of a late and lonely breakfast, with the additional sedative of a newspaper, there was an air of repose about his place of residence peculiar to itself, and which hangs about it, even in these times, when it is more bustling and busy than it was in days of yore.

There are, still, worse places than the Temple, on a sultry day, for basking in the sun, or resting idly in the shade. There is yet a drowsiness in its courts, and a dreamy dulness in its trees and gardens; those who pace its lanes and squares may yet hear the echoes of their footsteps on the sounding stones, and read upon its gates, in passing from the tumult of the Strand or Fleet Street, "Who enters here leaves noise behind." There is still the plash of falling water in fair Fountain Court, and there are yet nooks and corners where dun-haunted students may look down from their dusty garrets, on a vagrant ray of sunlight patching the shade of the tall houses, and seldom troubled to reflect a passing stranger’s form. There is yet, in the Temple, something of a clerkly monkish atmosphere, which public offices of law have not disturbed, and even legal firms have failed to scare away. In summer time, its pumps suggest to thirsty idlers, springs cooler, and more sparkling, and deeper than other wells; and as they trace the spillings of full pitchers on the heated ground, they snuff the freshness, and, sighing, cast sad looks towards the Thames, and think of baths and boats, and saunter on, despondent.

It was in a room in Paper Buildings — a row of goodly tenements, shaded in front by ancient trees, and looking, at the back, upon the Temple Gardens — that this, our idler, lounged; now taking up again the paper he had laid down a hundred times; now trifling with the fragments of his meal; now pulling forth his golden toothpick, and glancing leisurely about the room, or out at window into the trim garden walks . . . . [Vol. III, 13]

This particular setting seems to have been a favourite of Dickens, for it appears as the abode of a number of Dickens's young men: in The Old Curiosity Shop, Great Expectations, "Hunted Down," Our Mutual Friend, Martin Chuzzlewit, and A Tale of Two cities. Originally constructed on land belonging to the Knights Templar between Fleet Street and the river in 1608 as one of the Inns of Court for the legal profession, twenty of these residences suffered a catastrophic fire on 6 March 1838 — in other words, about three years before Dickens wrote this episode. Although the writer most closely associated with the Paper Buildings of the Inner Temple is John Galsworthy, who wrote his first work of fiction ("Dick Denver's Idea") here in November 1894, a number of Dickens's characters, including Sir John Chester, are associated with these chambers in the Inner Temple, London. The so-called Paper Buildings were constructed on the site of Heyward's Buildings (1610). The "paper" in their name is the result of their being constructed not from brick or stone, but from timber, lath, and plaster, a construction method known as "paperwork." Dickens as a young writer and associate of lawyers would have been familiar with the seventeenth-century apartments. The March 1838 a fire which broke out in the chambers of Member of Parliament W. H. Maule spread through some twenty sets of chambers in three of the buildings, destroying several private libraries containing important historical documents. Almost immediately work began to replace them with a novel design by architect Robert Smirke (1780–1867), with his younger brother, architect Sydney Smirke (1797–1877), in 1843 adding two more buildings with polygonal corner-turrets and Tudor-style chimneys. The whole project was complete by 1848.

Although Garden Court was largely rebuilt in 1830 and 1875-80, the rooms belonging to Mr. Chester in the eighteenth century would have looked much the same in the early nineteenth. Dickens's Sir John Chester in 1780 would probably be living in the Wren-designed, seventeenth-century red-brick block (numbers 1 through 4 of the Paper Buildings) on the west side of King's Bench Walk. In terms of other references to The Temple in Dickens, Chester is in good company, for characters as various as Pip and Herbert Pocket, Julius Slinkton, Mortimer Lightwood, and Eugene Wrayburn have lived in this area, and Tom Pinch's private library was located here. Finally, Dickens's legal advisor, John Forster, trained as an attorney in the Middle Temple in the early 1830s.

Parallel Scene from The Diamond and Household Editions (1867 and 1874)

Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior, seems to have had the same moment in mind since

in the interview Mr. Chester plies his toothpick:

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First illustrators: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Cattermole's seventeen illustrations (13 Feb.-27 Nov. 1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's six illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s ten Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 illustrations for the Household Edition (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's six illustrations for the Collins' Clear-Type Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

________. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. VI.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Vann, J. Don. "Charles Dickens. Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February-27 November 1841." New York: MLA, 1985. 65-66.

Created 5 July 2002

Last modified 5 December 2020