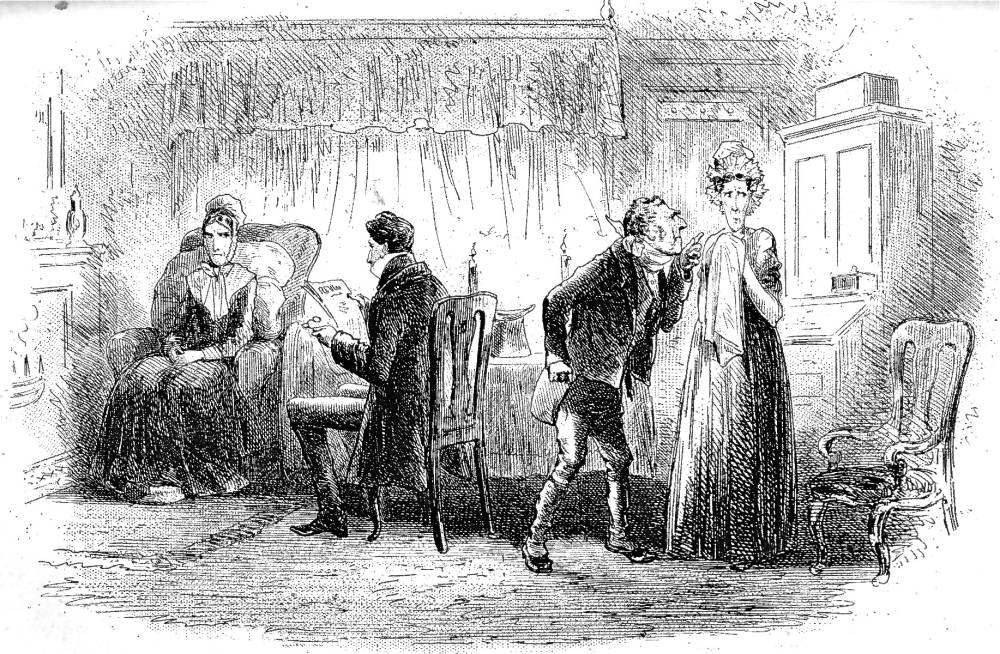

Missing and Dreaming by Phiz, twenty-ninth serial Illustration for "Little Dorrit" (Part 15: February 1857) by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the Second, "Riches"; Chapter 17, "Missing," facing p. 540. 10 cm high x 15.1 cm wide, vignetted. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

The question has been asked before," said Mrs. Clennam,"and the answer has been, No. We don't choose to publish our transactions, however unimportant, to all the town. We say, No."

"I mean, he took away no money with him, for example," said Mr. Dorrit.

"He took away none of ours, sir, and got none here."

"I suppose," observed Mr. Dorrit, glancing from Mrs. Clennam to Mr. Flintwinch, and from Mr. Flintwinch to Mrs. Clennam, "you have no way of accounting to yourself for this mystery?"

"Why do you suppose so?" rejoined Mrs. Clennam.

Disconcerted by the cold and hard inquiry, Mr. Dorrit was unable to assign any reason for his supposing so.

"I account for it, sir," she pursued after an awkward silence on Mr. Dorrit's part, "by having no doubt that he is travelling somewhere, or hiding somewhere."

"Do you know — ha — why he should hide anywhere?

"No."

It was exactly the same No as before, and put another barrier up. "You asked me if I accounted for the disappearance to myself," Mr. Clennam sternly reminded him, "not if I accounted for it to you. I do not pretend to account for it to you, sir. I understand it to be no more my business to do that, than it is yours to require that."

Mr. Dorrit answered with an apologetic bend of his head. As he stepped back, preparatory to saying he had no more to ask, he could not but observe how gloomily and fixedly she sat with her eyes fastened on the ground, and a certain air upon her of resolute waiting; also, how exactly the self−same expression was reflected in Mr. Flintwinch, standing at a little distance from her chair, with his eyes also on the ground, and his right hand softly rubbing his chin.

At that moment, Mistress Affery (of course, the woman with the apron) dropped the candlestick she held, and cried out, "There! O good Lord! there it is again. Hark, Jeremiah! Now!"

If there were any sound at all, it was so slight that she must have fallen into a confirmed habit of listening for sounds; but Mr. Dorrit believed he did hear a something, like the falling of dry leaves. The woman's terror, for a very short space, seemed to touch the three; and they all listened. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 17, "Missing" p. 540-541.

Commentary

The chief illustrators of the book in the nineteenth century, Phiz and James Mahoney, and the first great Dickens illustrator of the twentieth, Harry Furniss have all focussed on the same aspect of the plot of the fourteenth monthly part, Mr. Dorrit's reception at Mrs. Clennam's during his brief stay in London. Having seen his daughter Fanny married to the simple-minded but well-meaning Edmund Sparkler in Venice, Mr. Dorrit returns with Fanny and his new son-in-law to London to manage business affairs. While Edmund and Mrs. Sparkler settle into Mrs. Merdle's rooms in the London mansion while she is still in Italy, Mr. Dorrit pursues his quest for Rigaud. However, Mrs. Clennam, one of Rigaud's business associates, seems reluctant to release any information to Mr. Dorrit, who is naturally suspicious of the hard-headed businesswoman and her confederate, the devious Jeremiah Flintwinch. In Phiz's realisation of Mr. Dorrit's visit, Mr. Dorrit is the only character whose face we cannot clearly discern, so that he remains a distinctive voice from the text, and we cannot judge whether he has heard and been disturbed by the peculiar noise that Affery (right) has just heard. Particularly telling is the suspicious glance that Mrs. Clennam (left, in front of the fireplace as befits an invalid) bestows upon Mr. Dorrit as he reads her hand-bill about the missing Rigaud. Ironically, Flora Finching has already given Mr. Dorrit a copy of the hand-bill, which serves as his motivation to visit Mrs. Clennam in the first place.

The title of the chapter derives from Rigaud's inexplicable disappearance after visiting Mrs. Clennam's house in London:

It happened, fortunately for the elucidation of any intelligible result, that Mr. Dorrit had heard or read nothing about the matter. This caused Mrs.Finching, with many apologies for being in great practical difficulties as to finding the way to her pocket among the stripes of her dress at length to produce a police handbill, setting forth that a foreign gentleman of the name of Blandois, last from Venice, had unaccountably disappeared on such a night in such a part of the city of London; that he was known to have entered such a house, at such an hour; that he was stated by the inmates of that house to have left it, about so many minutes before midnight; and that he had never been beheld since. This, with exact particulars of time and locality, and with a good detailed description of the foreign gentleman who had so mysteriously vanished, Mr. Dorrit read at large. — Book 2, Ch. 17, p. 536.

Pertinent illustrations in other early editions, 1863 to 1910

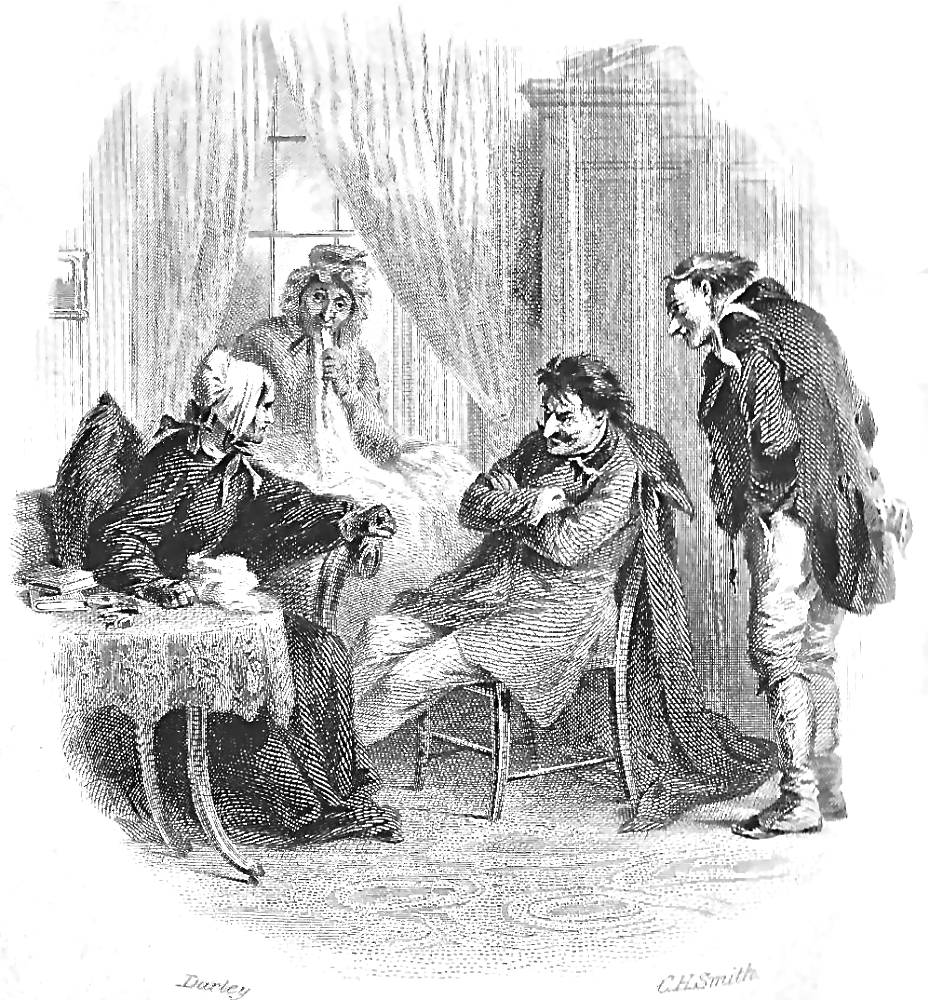

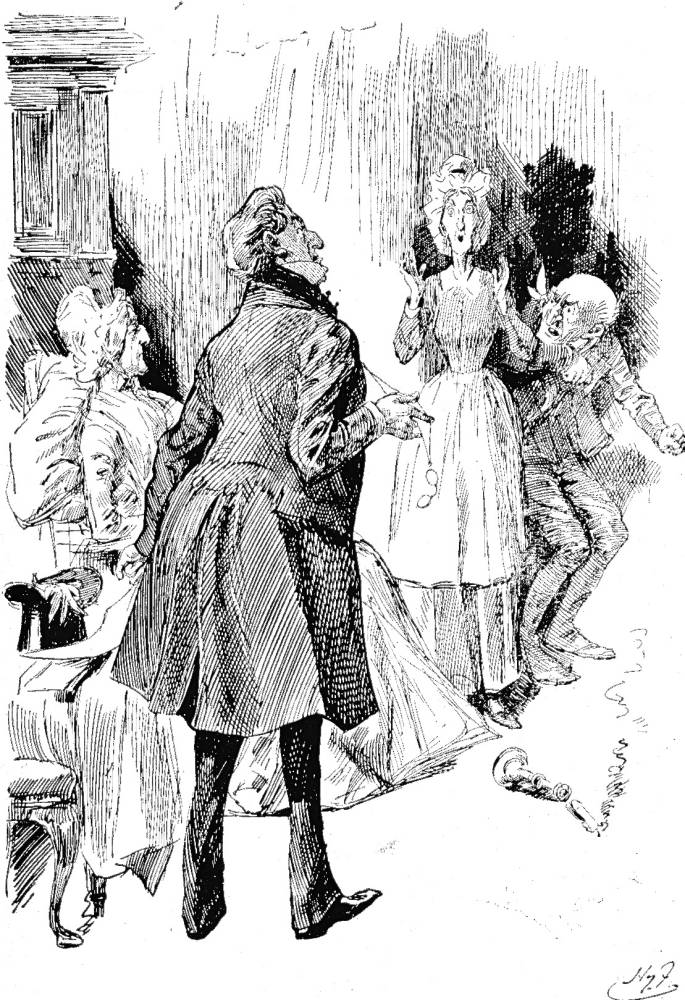

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's frontispiece featuring Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam, and Rigaud, Closing in (1863). Right: Harry Furniss's version of the same illustration, foregrounding Mrs. Clennam and Mr. Dorrit rather than placing them to one side, Mistress Affery's Alarm (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

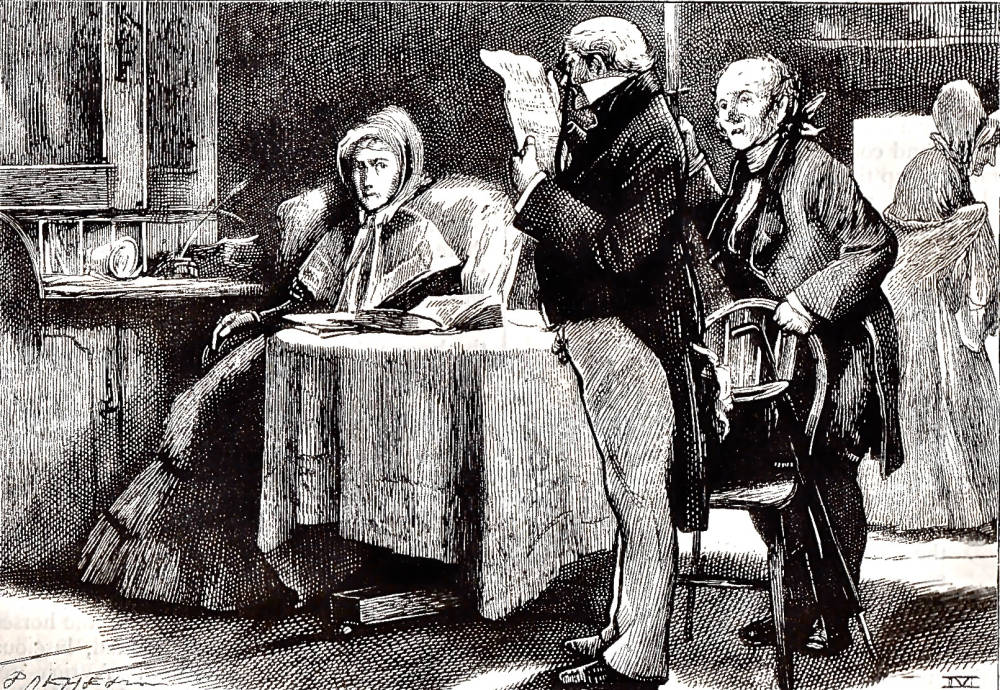

Above: James Mahoney's Household Edition illustration of the same scene, with Mr. Dorrit reading one of Mrs. Clennam's handbills, Mr. Dorrit read it through, as if he had not previously seen it (1873). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Phiz. The Authentic Edition. London:Chapman and Hall, 1901. (rpt. of the 1868 edition).

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 17 May 2016