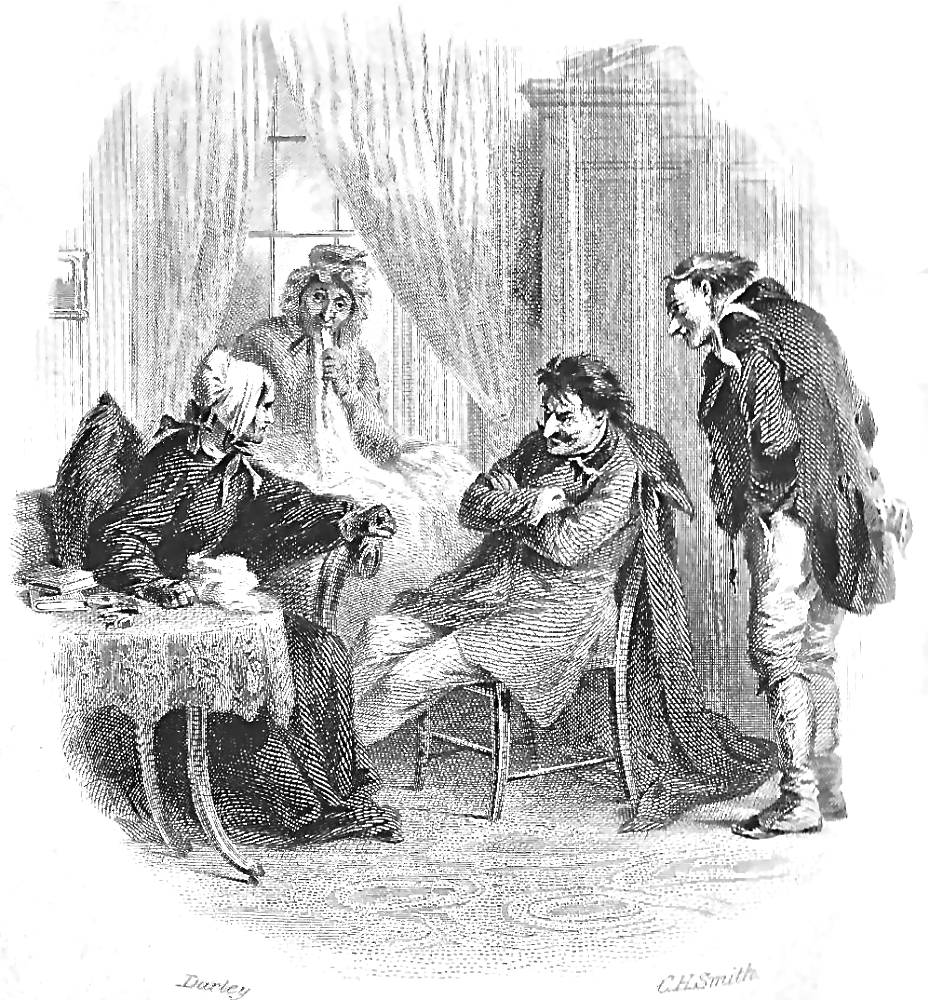

Mr. Flintwinch receives the Embrace of Friendship by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 10, "The Dreams of Mrs. Flintwinch thicken" (Part 13, December 1856), facing p. 470. 10.4 cm high by 17.8 cm wide, vignetted. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realised

The key of the door below was now heard in the lock, and the door was heard to open and close. In due sequence Mr. Flintwinch appeared; on whose entrance the visitor rose from his chair, laughing loud, and folded him in a close embrace.

"How goes it, my cherished friend!" said he. "How goes the world, my Flintwinch? Rose-coloured? So much the better, so much the better! Ah, but you look charming! Ah, but you look young and fresh as the flowers of Spring! Ah, good little boy! Brave child, brave child!"

While heaping these compliments on Mr. Flintwinch, he rolled him about with a hand on each of his shoulders, until the staggerings of that gentleman, who under the circumstances was dryer and more twisted than ever, were like those of a teetotum nearly spent.

"I had a presentiment, last time, that we should be better and more intimately acquainted. Is it coming on you, Flintwinch? Is it yet coming on?" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 10, "The Dreams of Mrs. Flintwinch thicken," p. 567.

Commentary

The drawing technique is characteristic of Browne's style in the late 1850s and early 1860s at its best, with a concern for composition, a pleasant handling of faces, and something of a sparseness of background details. [Steig, 166-167]

Indeed, the absence of emblemmatic details and visual commentary on the scene is quite remarkable, although, of course, Phiz here is exploiting the differences in height and body types for comedic effect and thoroughly enjoying the Englishman's discomfiture with the effusive affection of his French acquaintance. As always, Blandois is "insinuating" and horribly familiar, although here at least he is not smoking in the third chapter of the December 1856 (thirteenth monthly) instalment — perhaps out of deference to his hostess, a rigid Calvinist.

The other two figures in the scene constitute an audience for Blandois' flamboyant display of affection. To the right, Arthur Clennam (bearing a marked resemblance to his father, whose portrait hangs above the mantelpiece and its vases or urns) judges the pair critically. His gaze does not entirely match his "amazement, suspicion, resentment, and shame" (470). Her business dealings with both men, however, oblige Mrs. Clennam to view their behaviour with tolerance, but clearly she is viewing the affectionate greeting of Blandois with any enthusiasm. The gazes of both aloof mother and disapproving son direct the reader to study Jeremiah Flintwinch's rigid posture and controlled expression, his failure to reciprocate implied by his arms hanging limply at his sides: "reticent and wooden" indeed! Although it is not immediately apparent from the fireplace (left) and chest of drawers (rear), the scene is the invalide Mrs. Clennam's bedroom, as suggested by the canopy and side table (right), on which is a conspicuous detail — a book, probably (given her fundamentalist bent) a Bible.

The Crimean War having just ended with the capture of Sebastopol, the awkward friendship of the phlegmatic Briton, Jeremiah Flintwinch, and his effusive Gallic chum (who bears some resemblance to the Emperor of the French, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, otherwise, Napoleon III) may be a reflection of the uneasy alliance of Great Britain and France. As a Liberal opposed to Russian autocracy and expansionism, Dickens made no bones about being a Francophile in his framed tale in Household Words, for December 1854, "The Tale of Richard Doubledick" in The Seven Poor Travellers, and certainly the fall of the chief Russian port on the Black Sea on 8 September 1855 had vindicated Dickens's championing of the pact that resulted in Czar Alexander II's signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1856.

Blandois and Jeremiah Flintwinch in the Diamond, two Household and Charles Dickens Library Editions, 1863-1910

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's frontispiece for the fourth volume of the novel, Closing In — Book II, Chapter XXX. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the anxious Affery and her calculating husband, Mr. and Mrs. Flintwinch (1867). Right: a detail of the English and French villains, short Flintwinch and tall Blandois, Mrs. Clennam and the Plotters — a detail (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: James Mahoney's study of Rigaud (now, "Blandois"), Affery, and Arthur Clennam in this chapter, "Pray tell me, Affery," said Arthur, "who is this gentleman? (Book 2, Chapter 10, in the 1873 Household Edition). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ["Phiz"]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Authentic Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1867 edition]. Vol. 12.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books. London: B. T. Batsford, 1971.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 11 May 2016