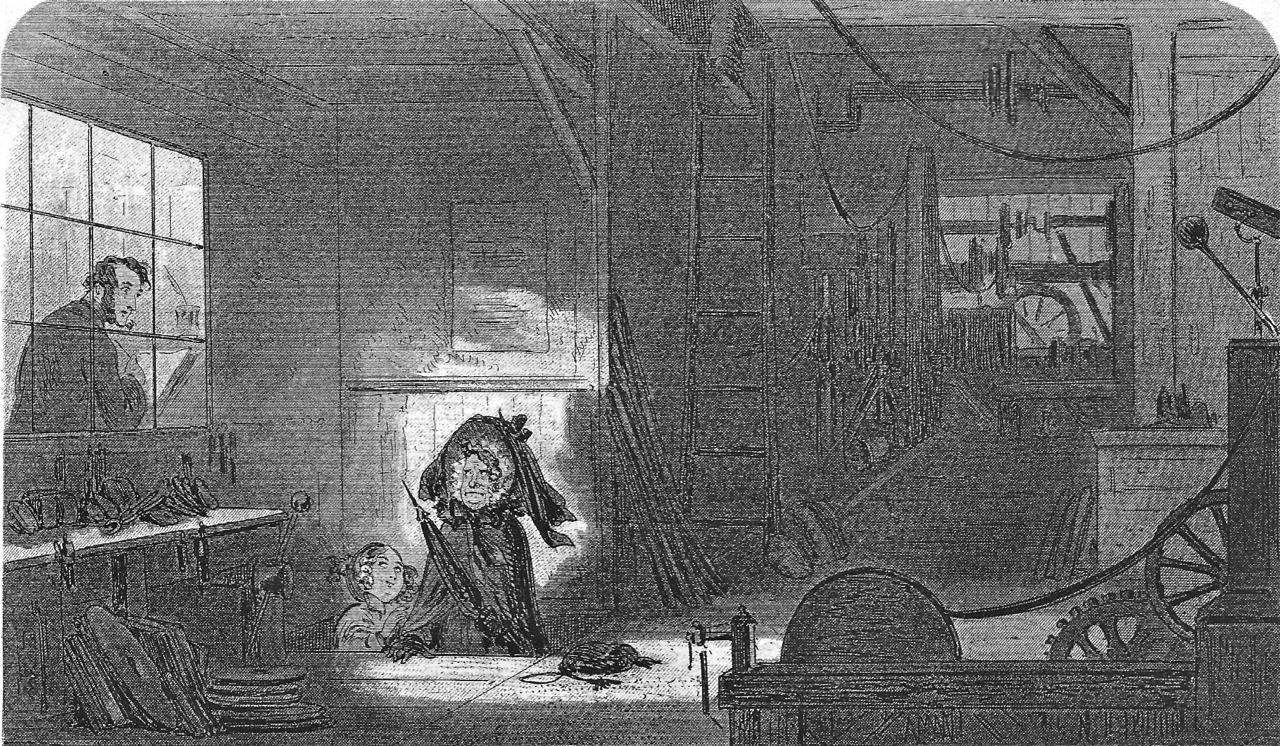

Visitors at the Works (facing p. 230) — originally, Phiz's fourteenth illustration for Dickens's Little Dorrit, Authentic Edition, 1901. A framed dark plate. Steel engraving for Book the First, "Riches," Chapter 23, "Machinery in Motion" (Part 7, June 1856). 9.7 cm high by 16.5 cm wide (3 ⅞ by 6 ½ inches), framed. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Unusual Visitors at the Works of Doyce and Clenham

The purchase was completed within a month. It left Arthur in possession of private personal means not exceeding a few hundred pounds; but it opened to him an active and promising career. The three friends dined together on the auspicious occasion; the factory and the factory wives and children made holiday and dined too; even Bleeding Heart Yard dined and was full of meat. Two months had barely gone by in all, when Bleeding Heart Yard had become so familiar with short-commons again, that the treat was forgotten there; when nothing seemed new in the partnership but the paint of the inscription on the door-posts, DOYCE AND CLENNAM; when it appeared even to Clennam himself, that he had had the affairs of the firm in his mind for years.

The little counting-house reserved for his own occupation, was a room of wood and glass at the end of a long low workshop, filled with benches, and vices, and tools, and straps, and wheels; which, when they were in gear with the steam-engine, went tearing round as though they had a suicidal mission to grind the business to dust and tear the factory to pieces. A communication of great trap-doors in the floor and roof with the workshop above and the workshop below, made a shaft of light in this perspective, which brought to Clennam's mind the child's old picture-book, where similar rays were the witnesses of Abel's murder. The noises were sufficiently removed and shut out from the counting-house to blend into a busy hum, interspersed with periodical clinks and thumps. The patient figures at work were swarthy with the filings of iron and steel that danced on every bench and bubbled up through every chink in the planking. The workshop was arrived at by a step-ladder from the outer yard below, where it served as a shelter for the large grindstone where tools were sharpened. The whole had at once a fanciful and practical air in Clennam's eyes, which was a welcome change; and, as often as he raised them from his first work of getting the array of business documents into perfect order, he glanced at these things with a feeling of pleasure in his pursuit that was new to him.

Raising his eyes thus one day, he was surprised to see a bonnet labouring up the step-ladder. The unusual apparition was followed by another bonnet. He then perceived that the first bonnet was on the head of Mr. F.'s Aunt, and that the second bonnet was on the head of Flora, who seemed to have propelled her legacy up the steep ascent with considerable difficulty. Though not altogether enraptured at the sight of these visitors, Clennam lost no time in opening the counting-house door, and extricating them from the workshop; a rescue which was rendered the more necessary by Mr. F.'s Aunt already stumbling over some impediment, and menacing steam power as an Institution with a stony reticule she carried.

"Good gracious, Arthur, — I should say Mr. Clennam, far more proper — the climb we have had to get up here and how ever to get down again without a fire-escape and Mr. F.'s Aunt slipping through the steps and bruised all over and you in the machinery and foundry way too only think, and never told us!"

Thus, Flora, out of breath. Meanwhile, Mr. F.'s Aunt rubbed her esteemed insteps with her umbrella, and vindictively glared. [Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 23, "Machinery in Motion," pp. 228-229.

Commentary

. . . seven of the eight dark plates occur in the first half of the novel; not one of the eight includes a single emblematic detail, consistent with a general reduction in Browne's use of such conceptual techniques. (Such a reduction, already discernible in Bleak House, becomes rapid for Phiz in the latter half of the 1850s, to the extent that by the end of the decade emblematic details have virtually disappeared from his work.) As a group, the Little Dorrit illustrations seem less necessary than those for Bleak House, and yet some enhance the novel, making its "dark" feeling visible, and underlining some of its themes by means of familiar iconographic techniques. [Steig, 158]

Having settled into his small counting-house that looks out of the second storey of the factory in Bleeding Heart Yard, Arthur Clennam is surprised by a visit from the dour Mr. F's Aunt and her jovial companion, the bubbly widow Flora Finching. The elderly lady emerges through the trapdoor with a look of disgust, while Flora, immediately below her, seems to be enjoying the experience of visiting Arthur in his place of work. However, Dickens's metonymy of the rising "bonnets," obvious in Phiz's illustration for both women, implies that such visitors are wholly inappropriate; even the enlightened Clennam is "not altogether enraptured at the sight of these visitors" (229) as they constitute an unwarranted interruption in his putting the business's documents in working order. The bonnets, therefore, constitute an antiphonal symbol of domesticity in contradiction to the dominant images of machinery and foundry.

If Mr. Doyce represents "uncommon sense," the intelligence of the engineer and innovator, Arthur as the accountant and man of good business practices represents "common sense." His counting-house, therefore, is very much an accounting office where, pen in hand (as suggested by the inkwell and the quill pen), he has straightened out the books of the firm in which, weeks earlier, he has purchased a joint interest. Phiz's picture clearly delineates the level above the factory floor, but does not indicate precisely what kind of industrial activity transpires on this level of the building in Bleeding Heart Yard.

Flora Finching and Mr. F's Aunt in the original, Diamond, and Charles Dickens Library Editions, 1856-1910

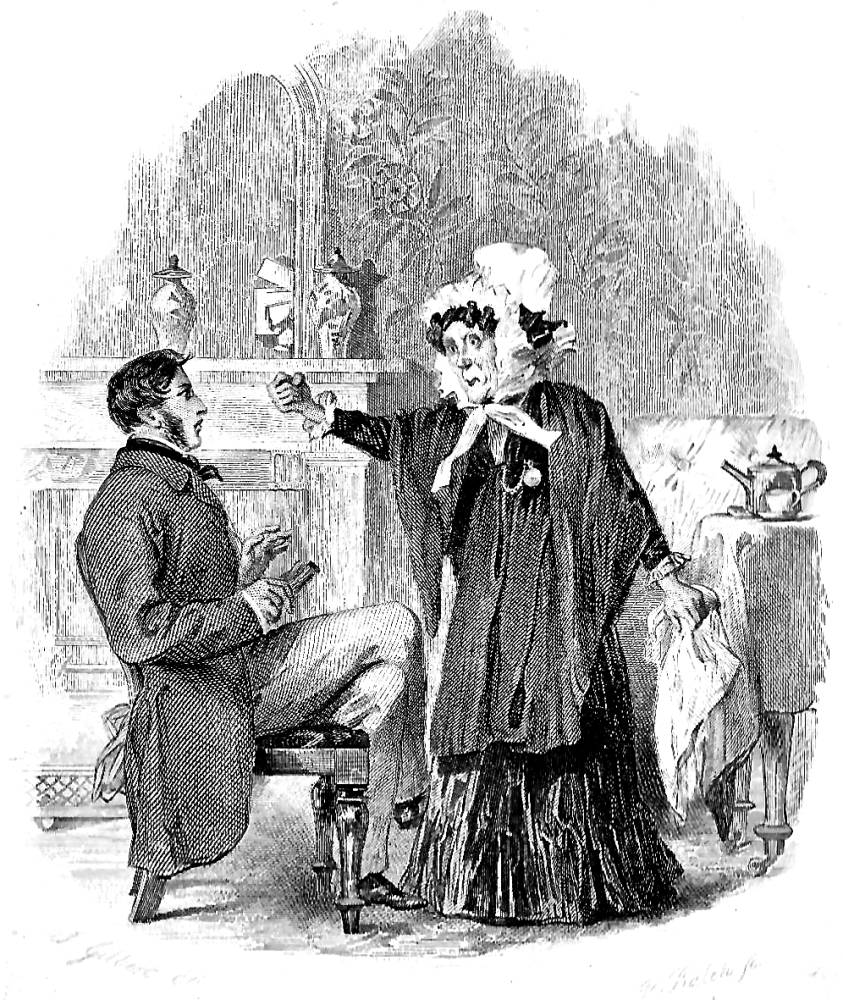

Left: Gilbert's 1863 frontispiece of the scene in which Mr. F's Aunt tries to force the startled Arthur Clennam to eat her left-over crust, "He's too proud a cap to eat it . . ." (Volume 3). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the demented Mr. F's Aunt and Flora Finching, Flora and Mr. F.'s Aunt (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 caricature of the demented old lady in the Charles Dickens Library Edition, Mr. F.'s Aunt. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration of Mr. F's Aunt trying to drive Arthur Clennam out of the Patriarchal mansion, Rigour of Mr. F's Aunt (Book II, Ch. 9; December 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Relevant Illustrated Editions of this Novel (1856 through 1910)

- Little Dorrit (homepage)

- Phiz's forty serial illustrations for Little Dorrit (December 1855—June 1857)

- F. O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- F. O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- F. O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- James Mahoney's 58 Household Edition Illustrations (1873)

- Harry Furniss's 29 Illustrations for Dickens's Little Dorrit, Vol. 12 in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Harvey, John. Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini. Character Sketches from Dickens. Illustrated by Harrold Copping. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. "Little Dorrit, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, December 1855 — June 1856." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 70-71.

Created 13 April 2016

Last modified 16 February 2025