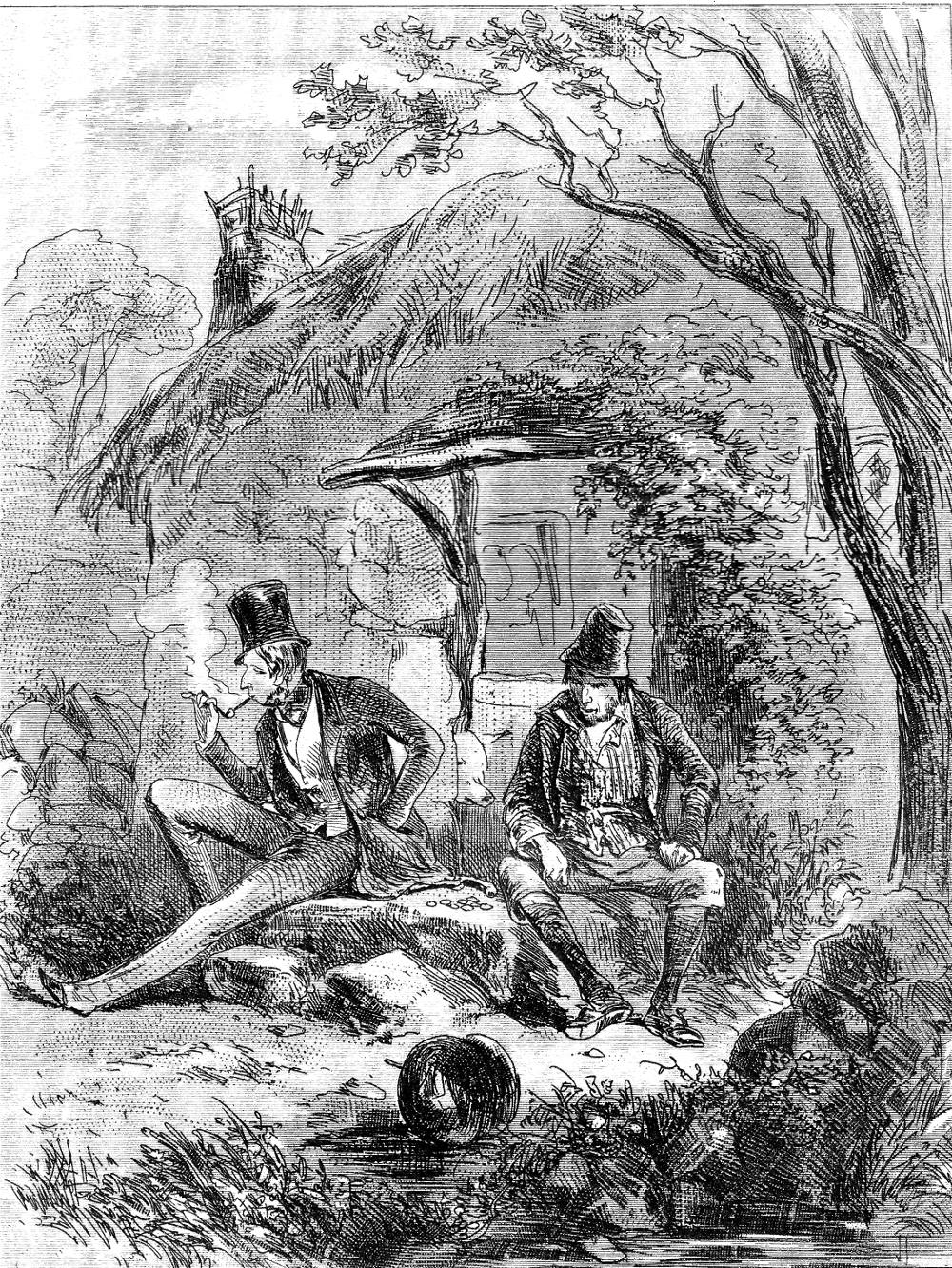

The Temptation

Phiz

Dalziel

July 1849

Steel-engraving, dark plate, facing p. 474.

12.5 cm high by 9.25 cm wide (4 ⅞ by 3 ¾ inches), framed.

Thirty-first illustration for Roland Cashel, published serially by Chapman and Hall (1848-49).

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the prson who scanned it and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Tom Linton exhorts Dan Keane to assassinate his Master

Dan Keane, the gate-keeper, sat moodily at his door on the morning after the events recorded in our last chapter. . . .

“'T is a lonely road that leads from Sheehan's Mill to the ould churchyard,” said Keane, more bent upon following out his own fancies than in attending to Linton.

“So I believe,” said Linton; “but Mr. Cashel cares little for its solitude; he rides always without a servant, and so little does he fear danger, that he never goes armed.”

“I heard that afore,” observed Tom, significantly.

“I have often remonstrated with him about it,” said Linton. “I've said, 'Remember how many there are interested in your downfall. One bullet through your forehead is a lease forever, rent free, to many a man whose life is now one of grinding poverty.' But he is self-willed and obstinate. In his pride, he thinks himself a match for any man — as if a rifle-bore and a percussion-lock like that, there, did not make the merest boy his equal! Besides, he will not bear in mind that his is a life exposed to a thousand risks; he has neither family nor connections interested in him; were he to be found dead on the roadside to-morrow, there is neither father nor brother, nor uncle nor cousin, to take up the inquiry how he met his fate. The coroner would earn his guinea or two, and there would be the end of it!”

“Did he ever do you a bad turn, Mr. Linton?” asked Keane, while he fixed his cold eyes on Linton with a stare of insolent effrontery.

“Me! injure me? Never. He would have shown me many a favour, but I would not accept of such. How came you to ask this question?”

“Because you seem so interested about his comin' home safe to-morrow evening,” said Dan, with a dry laugh.

“So I am!” said Linton, with a smile of strange meaning.

“An' if he was to come to harm, sorry as you 'll be, you couldn't help it, Sir?” said Keane, still laughing.

“Of course not; these mishaps are occurring every day, and will continue as long as the country remains in its present state of wretchedness.”

Keane seemed to ponder over the last words, for he slouched his hat over his eyes, and sat with clasped hands and bent-down head for several minutes in silence. At last he spoke, but it was in a tone and with a manner whose earnestness contrasted strongly with his former levity.

“Can't we speak openly, Mr. Linton, wouldn't it be best for both of us to say fairly what's inside of us this minit?”

"I'll wager you ten sovereigns in gold — there they are — that I can keep a secret as well as you can.”

As he spoke, he threw down the glittering pieces upon the step on which they sat.

The peasant's eyes were bent upon the money with a fierce and angry expression, less betokening desire than actual hate. As he looked at them, his cheek grew red, and then pale, and red once more; his broad chest rose and fell like a swelling wave, and his bony fingers clasped each other in a rigid grasp.

“There are twenty more where these came from,” said Linton, significantly. [Chapter LVII, "Linton Instigates Keane to Murder," pp. 472-477]

Commentary: A Contrast in Backgrounds, not in Character

Linton has already persuaded Dan Keane that Cashel intends to discharge him from his post as Tubbermore gatekeeper after forty-two years of service on the estate. Needless to say, the surly Dan is upset, feeling himself unjustly fired. Thus, Linton manipulates him into agreeing to shoot Cashel, who has just escaped a duel with the aged Lord Kilgoff. And of course Linton must eliminate Cashel as a rival for Mary Leicester's hand if he is to execute his plan to use George III's bond to take over Cashel's estates.

In Phiz's illustration set at the gatekeeper's dilapidated cottage, Dan sits in a stupor of despair as he stares vacantly down at his feet. Turned off the land his family have lived on for centuries, the indolent gatekeeper sees no future for himself and his children. Linton, immaculately dressed in the latest fashion, casually smokes a cigar, apparently unaffected by Dan's (supposed) fate to be turned out without being the opportunity to emigrate to America. The empty vessel seems a symbol for Keane's despair at suddenly finding himself without his sinecure. Since Phiz shows Linton in the very act of casually lighting his cigar, the precise moment realized is this:

“Precisely so. You remember it yourself, before Mr. Cashel's time; and so it might be again, if he should try any harsh measures with those Drumcoologan fellows. Let me light my cigar from your pipe, Keane,” said he; and, as he spoke, he laid down the pistol which he had still carried in his hand. Keane's eyes rested on the handsome weapon with an expression of stern intensity. [475]

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Roland Cashel. With 39 illustrations and engraved title-vignette by Phiz. London: Chapman & Hall, 1850.

Lever, Charles. Roland Cashel. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablot Knight Browne]. Novels and Romances of Charles Lever. Vols. I and II. In two volumes. Boston: Little, Brown, 1907. Project Gutenberg. Last Updated: 19 August 2010.

Steig, Michael. Chapter Seven: "Phiz the Illustrator: An Overview and a Summing Up." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 298-316.

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Roland

Cashel

Next

Created 19 January 2023