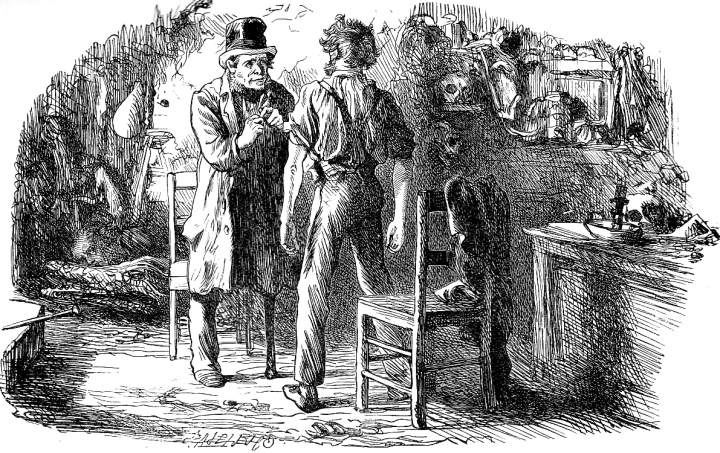

Mr. Wegg prepares a Grindstone for Mr. Boffin's Nose by Marcus Stone. Wood engraving by Dalziel. 9.5 cm high x 14.4 cm wide. Second illustration for the fourteenth monthly number of Our Mutual Friend, Chapter Fourteen, "Mr. Wegg prepares a Grindstone for Mr. Boffin's Nose," in the third book, "A Long Lane." The Authentic edition, facing p. 506. [This part of the novel originally appeared in periodical form in May 1865.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The setting is once again, as in "Mr. Venus Surrounded by the Trophies of His Art" (June 1864), the taxidermist's shop of the melancholy, rejected suitor Mr. Venus, where, with Boffin hiding behind the stuffed alligator, the moral artisan draws out Wegg about his feelings regarding Boffin as a result of the suppositous will that invalidates most of the Golden Dustman's claim to the Harmon estate:

'My time, sir,' returned Wegg, 'is yours. In the meanwhile let it be fully understood that I shall not neglect bringing the grindstone to bear, nor yet bringing Dusty Boffin's nose to it. His nose once brought to it, shall be held to it by these hands, Mr. Venus, till the sparks flies out in showers.' [506]

As Wegg rants about Boffin's being made to pay for Wegg's silence regarding the second will, Boffin listens safely from his place of hiding, behind the young alligator. This time, however, in contrast to the former illustration, the artist's interest is not so much Venus's shop and its macabre contents as the two characters who discuss how they may transform the waste of the mounds into gold through blackmail. Venus is easily distinguished by his shock of ginger hair and leather apron, Wegg by his top hat and peg leg. The ubiquitous grinning skulls supplied by the illustrator suggest, as does Dickens's mention of the French gentleman (the articulated skeleton), suggest that there are eavesdroppers on this very private conversation.

Everything else, however, looks different because Stone has changed the orientation of the picture of Venus's shop; formerly, we regarded Venus's counter and fireplace from within, so that the window formed the backdrop. Now, the counter is to the right, and the fireplace is apparently behind the conspirators, so that the viewer has been given a different perspective. Similarly, the reader now regards the lovelorn taxidermist in a different light after his revelations to Boffin — and his refusal to be bribed to suppress or hand over the will. The unlit candle on the corner of the counter is faithful to Dickens's text, although the room is rather better lit. Moreover, Stone's placing the alligator on the floor does not seem plausible, since Venus instructs Boffin to draw in his legs:

The Golden Dustman seemed about to pursue these questions, when a stumping noise was heard outside, coming towards the door. 'Hush! here's Wegg!' said Venus. 'Get behind the young alligator in the corner, Mr. Boffin, and judge him for yourself. I won't light a candle till he's gone; there'll only be the glow of the fire; Wegg's well acquainted with the alligator, and he won't take particular notice of him. Draw your legs in, Mr. Boffin, at present I see a pair of shoes at the end of his tail. Get your head well behind his smile, Mr Boffin, and you'll lie comfortable there; you'll find plenty of room behind his smile. He's a little dusty, but he's very like you in tone. Are you right, sir?' [503]

Boffin (lower left) seems all too conspicuous to the viewer, who must exercise some suspension of disbelief. Nevertheless, the change in perspective may account for the reptile's not being visible in the previous scene, and his general dustiness may imply that he has been stored away in a corner on the floor rather than hanging from the ceiling. The stratagem of hiding an eavesdropper behind an alligator may be derived from the John Gay-Alexander Pope-John Arthbuthnot 1717 dramatic collaboration Three Hours After Marriage, in which the butt of the farcical satire is Dr. Fossil, a natural philosopher who is being cuckolded. Regarded as obscene, the play was not performed again after its sell-out run at Drury Lane, so that Dickens could have known of it only through his reading in the British Library, or through his extensive knowledge of London stage history.

References

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901.

Last modified 10 July 2011