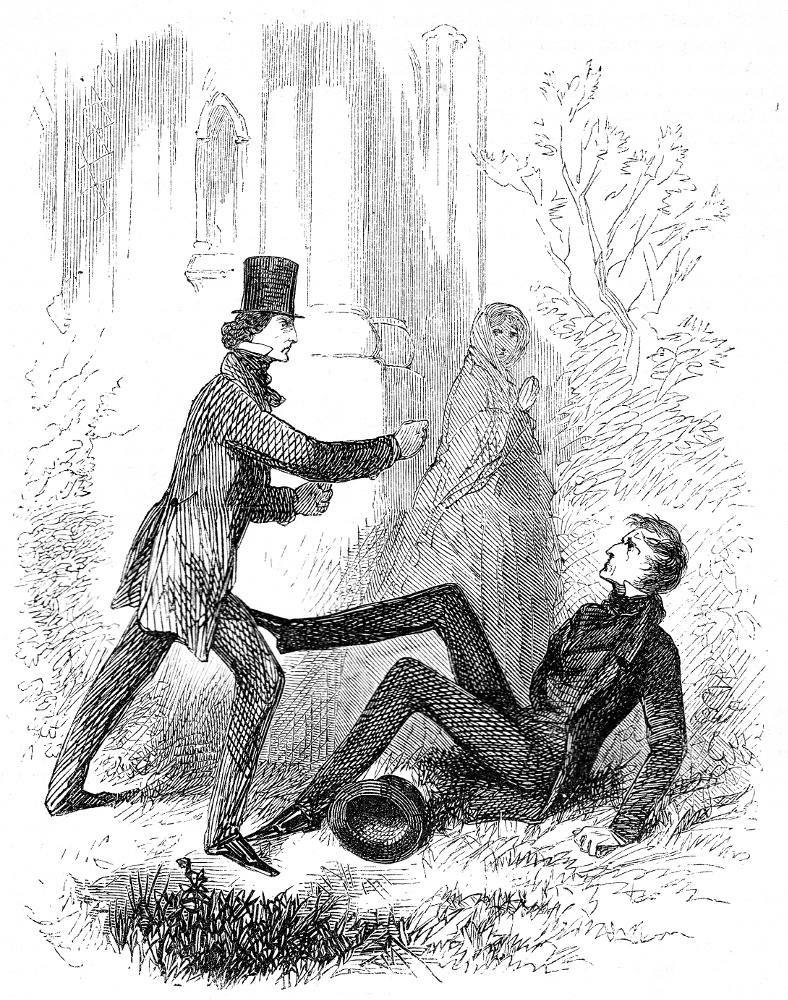

He fell into a kind of frenzy at his own disgrace, and struck Sir Percival.

John McLenan

23 June 1860

11.3 cm high by 8.8 cm wide (4 ¼ by 3 ½ inches), vignetted, p. 380; p. 196 in the 1861 volume.

Thirty-first regular illustration for Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (1860).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.