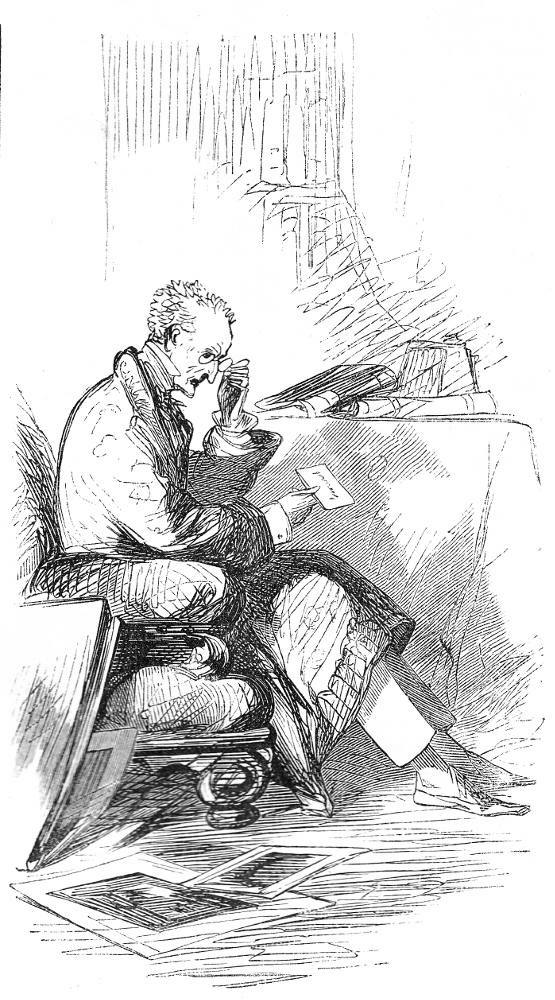

Frederick Fairlie is disturbed by a letter he has just received

John McLenan

21 April 1860

10.2 cm high by 5.9 cm wide (4 by 2 ¼ inchess), vignetted.

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for the twenty-second weekly number of Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (21 April 1860), 253; p. 144 in the 1861 volume.

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The illustration marks the breaking off of Marian's narrative as she succumbs to a fever. The next entry, then, is not hers at all, as Collins introduces Mr. Fairlie's contribution in the middle of the serial number.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.