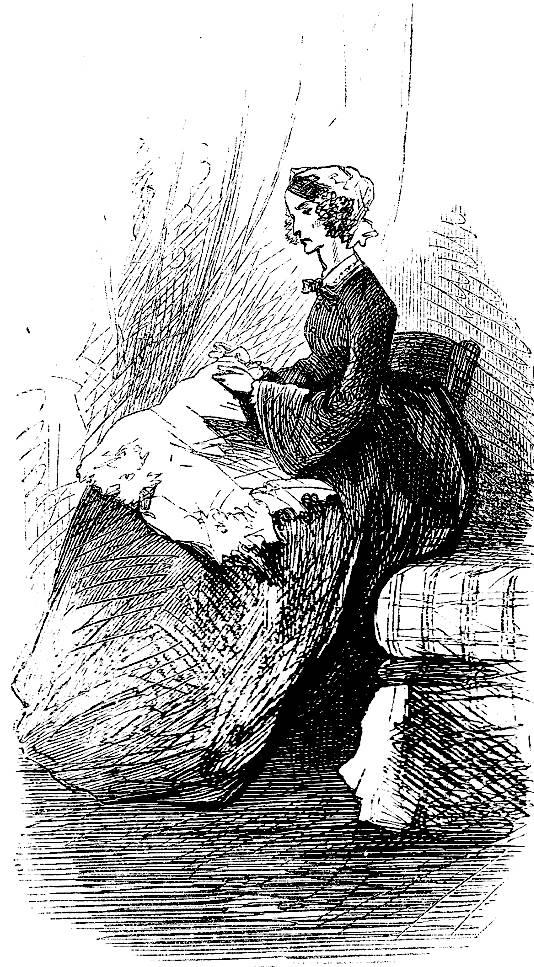

Madame Fosco doing embroidery.

John McLenan

18 February 1860

9.8 cm high by 5.4 cm wide (3 &frac;34 by 2 ⅛ inches), framed, p. 85; p. 90 in the 1861 volume edition.

Tenth headnote vignette for Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (1860).

Formerly a somewhat fractious young English woman who refused to abide by the proprieties and restrictions imposed upon upper-middle-class females, Laura's aunt, the former Eleanor Fairlie, is now (at least outwardly) the decorous Victorian wife. She has gone from frivolous to austere under her husband's tutelage.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.