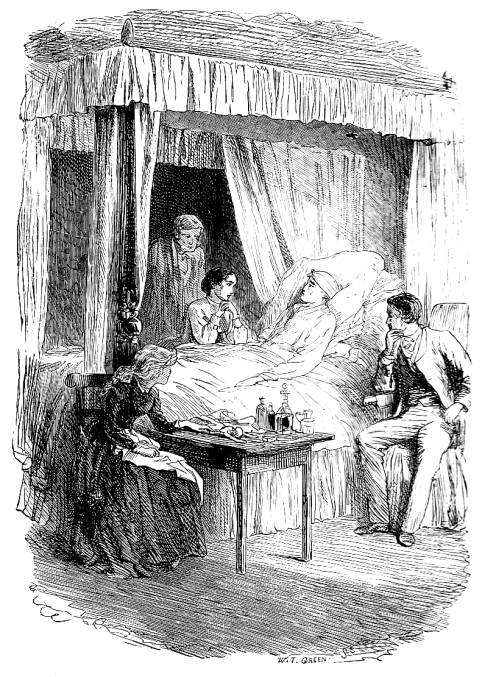

Miss Jenny gave up altogether on this parting taking place between the friends, and sitting with her back towards the bed in the bower made by her bright hair, wept heartily, though noiselessly. (p. 312) —James Mahoney's fifty-third illustration for Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Household Edition, 1875, has the same lengthy caption in both the New York and London printings. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high x 13.3 cm wide. The composite wood-engraving concerns Jenny's despairing of Eugene's recovery after the attack by the river, the other figure in the picture being Mortimer Lightwood, who has conducted her from London to Eugene's bedside in an inn far up the Thames, near Plashwater weir, where Lizzie brought him more than dead than alive in Book Four, Ch. 6, "A Cry for Help."

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Realised

Glancing wistfully around, Eugene saw Miss Jenny at the foot of the bed, looking at him with her elbows on the bed, and her head upon her hands. There was a trace of his whimsical air upon him, as he tried to smile at her.

"Yes indeed," said Lightwood, "the discovery was hers. Observe, my dear Eugene; while I am away you will know that I have discharged my trust with Lizzie, by finding her here, in my present place at your bedside, to leave you no more. A final word before I go. This is the right course of a true man, Eugene. And I solemnly believe, with all my soul, that if Providence should mercifully restore you to us, you will be blessed with a noble wife in the preserver of your life, whom you will dearly love."

"Amen. I am sure of that. But I shall not come through it, Mortimer."

"You will not be the less hopeful or less strong, for this, Eugene."

"No. Touch my face with yours, in case I should not hold out till you come back. I love you, Mortimer. Don't be uneasy for me while you are gone. If my dear brave girl will take me, I feel persuaded that I shall live long enough to be married, dear fellow."

Miss Jenny gave up altogether on this parting taking place between the friends, and sitting with her back towards the bed in the bower made by her bright hair, wept heartily, though noiselessly. Mortimer Lightwood was soon gone. As the evening light lengthened the heavy reflections of the trees in the river, another figure came with a soft step into the sick room.

"Is he conscious?" asked the little dressmaker, as the figure took its station by the pillow. For, Jenny had given place to it immediately, and could not see the sufferer's face, in the dark room, from her new and removed position.

"He is conscious, Jenny," murmured Eugene for himself. "He knows his wife." — Book Four, Chapter 10, "The Doll's Dressmaker Discovers a Word," p. 313.

Commentary: At Eugene's Beside: Sick-bed or Death-bed?

As is the case with the comic subplot involving Fledgeby and the Lammles, Jenny Wren is a connecting presence. Immediately after the scene in which she mortifies Fascination Fledgeby for his posturing and deceit she appears in this gravely serious scene at the foot of Eugene's bed, perhaps his deathbed. Marcus Stone in a similar composition entitled simply Eugene's Bedside facilitated the chapter's creating suspense by inserting the one figure not mentioned in the chapter previous to its conclusion, the minister who will marry Lizzie and Eugene. Through his lengthy caption Mahoney makes it plain that Jenny Wren and Mortimer Lightwood are at Eugene's bedside, but avoids showing the other characters so that the reader must consult and complete perusal of the text in order to assess the situation accurately, and discover from the closing line of the chapter that Lizzie has finally accepted Eugene's marriage proposal. Mahoney's handling of the scene is therefore much more emotional than Stone's as Jenny breaks down at the foot of the bed, and his illustration gives no indication as to whether Eugene will recover or will marry Lizzie, who is not shown. An odd repetition is occasioned by Eugene's head-bandage, which resembles the Turkish pasha headgear of Fascination Fledgeby, whose comeuppance at the hands (and fists) is so poetically just.

Although numerous characters are regularly killed off in modern action films, such was not the case in Victorian literature. The death of poet Arthur Henry Hallam, for example, had so profound an effect on his young colleague, Alfred Lord Tennyson, that he ceased publishing for a time and then produced one of the century's most significant works, In Memorian A. H. H. (1850). In the realm of the popular novel, the impending death of Little Nell in Dickens's The Old Curiosity Shop sparked a tidal wave of lachrymose emotions in serial readers on both sides of the Atlantic. Although today critics often regard sentimentality as the great failing of Victorian literature, writers such as Dickens were masters at manipulating readers' sentimental responses to scenes of death as set pieces for thematic and even political purposes, as the death of Jo the crossing-sweeper in Bleak House and Little Dick in Oliver Twist pointedly suggest. Sometimes, Dickens merely alludes to the death, revealing its impact on living, but in certain death-bed scenes Dickens almost wallows editorially in grief, describing a character's passing with heightened rhetoric and moving detail, almost directing the reader how and what to feel in response to the character's suffering. Thus, the serial readers of Our Mutual Friend in the autumn of 1865 could reasonably have expected that, despite his personal merits and importance to the plot, Eugene Wrayburn would die from injuries he sustained in Bradley Headstone's brutal assault. A greater source of suspense, perhaps, would have been whether Lizzie Hexam, the self-reliant girl of the working class, would agree to marry the young attorney on his death-bed in the waterside inn where she had taken him, unconscious, after rescuing him from drowning.

Since Dickens was master of the death-bed scene, Mahoney had a number of visual antecedents to consult for what, at first blush, is yet another death-bed scene, but turns out to be a near-death experience paralleling that of both John Harmon and Rogue Riderhood earlier in Our Mutual Friend. Here, once again, is the "returned-to-life" motif that dominates the 1859 historical novel A Tale of Two Cities (1859), in which the ghost of Terese Defarge's murdered brother cries "Vengeance!" from beyond the grave, although the pathetic scene in which he dies at the hands of the brothers Ste. Evrémonde does not occur in the original pictorial sequence provided by the 1859 illustrator, Phiz, and had to await realisation by Fred Barnard in the 1870s Household Edition. However, here in the closing numbers of Our Mutual Friend Dickens does not raise the reader's indignation or attempt to exploit the death of an innocent and blameless young person, as in George Cattermole's At Rest (Nell dead) in The Old Curiosity Shop (30 January 1841). Nor does Dickens dare to exploit the death-bed for ironic humour as he does in Hablot Knight Browne's I find Mr. Barkis "going out with the tide" in David Copperfield (February 1850). Although Mahoney probably could not draw on Eytinge's 'Poor Tiny Tim!' in the 1868 A Christmas Carol, he would have appreciated the sentimental appeal of the parent praying beside the bed of the dead or dying child. The grievers in this 1875 Mahoney plate are a good friend and an acquaintance, and the person dying is hardly a child, but rather the victim of an unprovoked assault, so that this scene is actually atypical in a Dickens novel, as opposed to Orlick's assault on the shrewish Mrs. Joe in Great Expectations (1861) and the pathetic death of "The Back Attic" in The Chimes (December 1844), a scene that illustrators such as Charles Green in The Death-Bed (1912) have depicted, but that Dickens himself never actually described. Unlike the unfaithful and dissolute Edson in Mrs. Lirriper in E. G. Dalziel's illustration for Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy (1864), Eugene Wrayburn does not deserve this suffering, so that his death would be an awkward reversal of Nemesis or Poetic Justice, as opposed to the self-destruction that Destiny visits upon the neurotic Bradley Headstone, in whose death sentimentality plays no part.

Relevant illustrations of Death-bed Scenes in Dickens

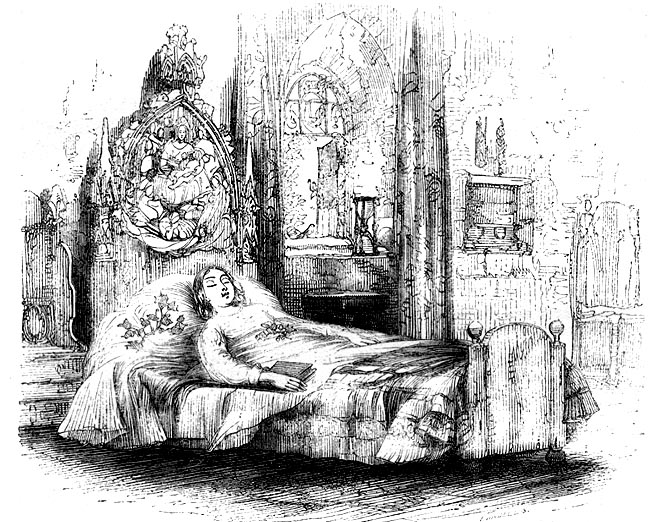

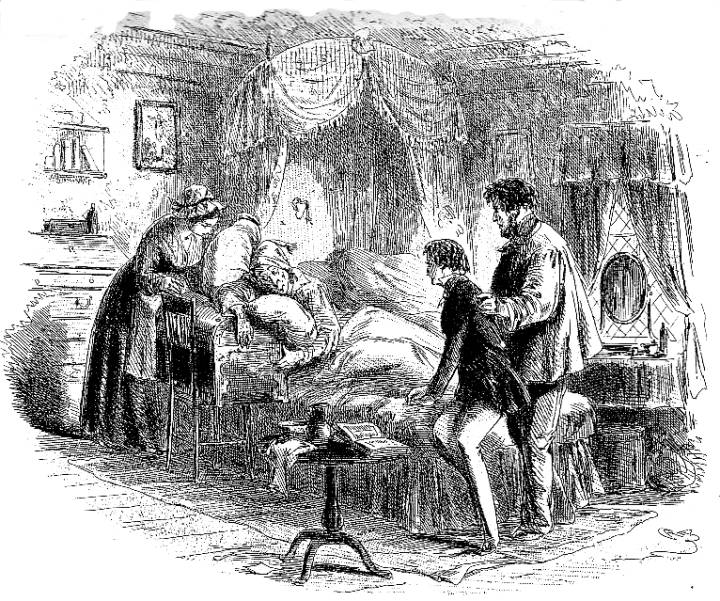

Left: George Cattermole's study of innocence too pure for this world, Little Nell Dead (1841). Centre: Hablot Knight Browne's February 1850 serial illustration of the death of the miserly tranter, I find Barkis "going out with the tide".Right: Marcus Stone's October 1865 serial illustration of Eugene's Bedside, in which the illustrator shows Jenny Wren, Lizzie Hexam, Mortimer Lightwood — and an Anglican minister, who has arrived to marry the couple. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Fred Barnard's Household Edition realisation of the death of Madame Defarge's brother at the hands of the Ste. Evrémondes, Twice he put his hand to the wound in his breast, and with his forefinger drew a cross in the air (Book 3, ch. viii). Right: Marcus Stone's October 1865 serial illustration of Eugene's Bedside, in which the illustrator shows Jenny Wren, Lizzie Hexam, Mortimer Lightwood — and an Anglican minister, who has arrived to marry the couple. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: E. G. Dalziel's 1868 interpretation of the death of Edson, Mrs. Lirriper for the 1864 Christmas story. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Illustrated Household Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Field; Lee and Shepard; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1870 [first published in The Diamond Edition, 1867].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall' New York: Harper & Bros., 1875.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's 'Our Mutual Friend': A Publishing History. Burlington, VT, and Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105. http://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Harpers/Harpers.htm

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 14 January 2016