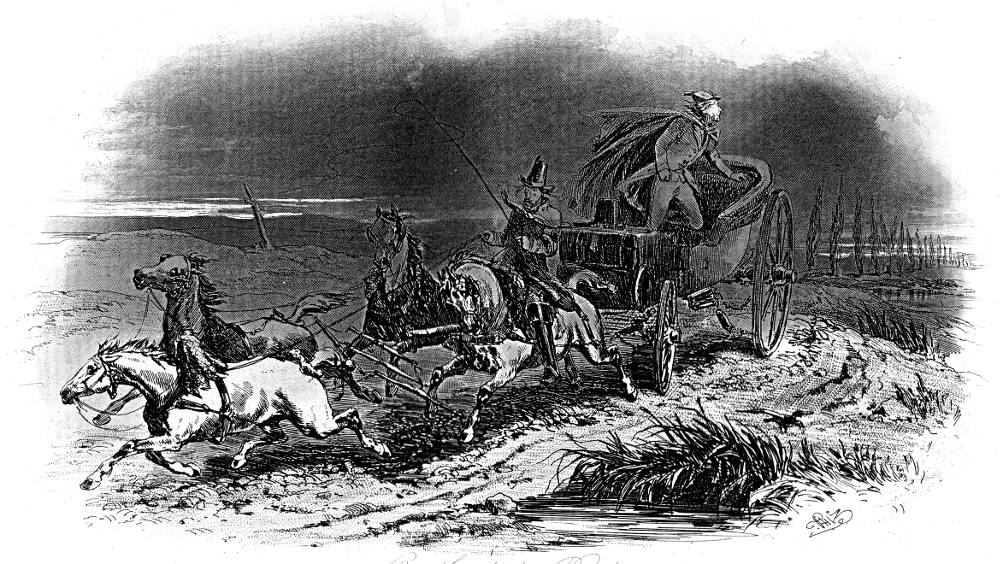

The sun had gone down full four hours, and it was later than most travellers would like it to be for finding themselves outside the walls of Rome, when Mr. Dorrit's carriage, still on its last wearisome stage, rattled over the solitary campagna — Book 2, chap. xix, is the full title as given in the Harper and Brothers printing. The Chapman and Hall edition has a much shorter, wholly different title: At some turns of the road, a pale flare on the horizon . . . . showed that the city was yet far off. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's forty-third composite woodblock illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high by 13.6 cm wide, p. 321, framed, under the running head "The Handbill." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

The sun had gone down full four hours, and it was later than most travellers would like it to be for finding themselves outside the walls of Rome, when Mr. Dorrit's carriage, still on its last wearisome stage, rattled over the solitary Campagna. The savage herdsmen and the fierce-looking peasants who had chequered the way while the light lasted, had all gone down with the sun, and left the wilderness blank. At some turns of the road, a pale flare on the horizon, like an exhalation from the ruin-sown land, showed that the city was yet far off; but this poor relief was rare and short-lived. The carriage dipped down again into a hollow of the black dry sea, and for a long time there was nothing visible save its petrified swell and the gloomy sky.

Mr. Dorrit, though he had his castle-building to engage his mind, could not be quite easy in that desolate place. He was far more curious, in every swerve of the carriage, and every cry of the postilions, than he had been since he quitted London. The valet on the box evidently quaked. The Courier in the rumble was not altogether comfortable in his mind. As often as Mr. Dorrit let down the glass and looked back at him (which was very often), he saw him smoking John Chivery out, it is true, but still generally standing up the while and looking about him, like a man who had his suspicions, and kept upon his guard. Then would Mr. Dorrit, pulling up the glass again, reflect that those postilions were cut-throat looking fellows, and that he would have done better to have slept at Civita Vecchia, and have started betimes in the morning. But, for all this, he worked at his castle in the intervals. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 19, "The Storming of the Castle in the Air," p. 326.

Commentary

William Dorrit, having come into a fortune and joined the ranks of the upper middle class, has engaged the "polishing" services of the pretentious Mrs. Hortensia General, widow of an army officer, to educate his daughters and prepare them for their new position in society. Now, as he returns in haste from his brief business trip to London, Mr. Dorrit builds castle in the air as he contemplates married life with Mrs. General, little realising that his health both mental and physical has been so compromised by the trip that he will not live long enough to propose marriage to that pillar of propriety, prunes, and prism.

Back from a hurried London trip, like Charles Dickens in December 1844 when he briefly visited his publishers to superintend the publication of the second Christmas Book, The Chimes, through the press and read the novella aloud to a select audience at 58 Lincoln's Inn Fields on the evening of 3 December 1844, William Dorrit must be exhausted. Called away from Rome to manage his financial affairs, he has had unsettling interviews with Mrs. Clennam and John Chivery, the latter being an embarrassing reminder of his former identity as Father of the Marshalsea. Now, still shocked by threat of exposure of his former life, he returns to the family in Rome, but the dark plate is full of foreboding, as if foreshadowing his physical and mental collapse at the farewell Merdle dinner, and his death ten days thereafter.

A useful point of comparison is not an illustration for Little Dorrit, but On the Dark Road, the steel-engraving for Chapter 55 of Dombey and Son by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) twenty-five years earlier. According to Valerie Lester Browne, this was Phiz's first attempt at a classic 'dark plate', in this case to show the futility of the villainous Carker's trying to cheat death as he returns to England to confront Mr. Dombey. The 1848 illustration, moreover, engages the viewer with the sharpness and vivacity of the figures and the prancing horses — horses having been from his earliest compositions one of Phiz's strengths. Better reproductions of this delightful illustration convey the aerial perspective through making clear the line of Lombardy poplars running off the the horizon, upper right.

For the illustration, 'On a dark road,' Phiz turned the plate horizontally and used a ruling machine, which pushed a bank of needles across the wax ground on the plate, creating a background of narrow stripes, akin to mezzotinting. (The technique is sometimes referred to as 'machine tinting'.) He then drew into dark areas to make them blacker and produced a variety of greys by stopping-out other areas. To retain the dazzling whites, he burnished away the ruled lines and stopped out those areas completely on the first and all subsequent visits to the acid. [Browne Lester, p. 135]

The dark plate becomes ubiquitous among Browne's etchings in the late forties and through the fifties, and it is as well to explain the technique at this point. In its most basic form it provides a way of adding mechanically ruled, very closely spaced lines to the steel in order to produce a "tint," a grayish shading of the plate. It is this simple method that Browne occasionally used for authors other than Dickens. But in general he made more subtle and complex use of the dark plate. . . . . The highlights, areas which were to remain white, would be stopped out with varnish, and then the biting could commence. Those areas which were to be lightest in tint would be stopped out after a short bite, the next lightest after a longer bite, and so on down to the very blackest areas — which would never, except where wholly exposed by the needle, become totally black, but would shimmer with the tiny lights of the unexposed bits between the ruled lines; the darkest sky in On the Dark Road has these little lights, while the dark parts of the puddle have none, apparently having been exposed to the acid by the needle rather than the ruling machine. [Steig, p. 106-107]

An ominous and menacing atmosphere surrounds each carriage as the onset of darkens implies impending doom, although the characters and horses in the Phiz engraving are more sharply delineated than the driver, passenger, and horses passing rapidly through Roman Campagna in the Mahoney wood-engraving, which has a rougher, less polished and precise effect, coinciding with the coarseness of the landscape and the peasantry which Dickens describes in the accompanying text. In particular, Phiz's horses are far more dynamic and precisely drawn than Mahoney's two, highlighted horses of much more solid build. Moreover, whereas Phiz has the open coach or barouche approaching the viewer, with an apparent break in the clouds throwing the face of the standing figure, the lead horse, the body of the postillion's horse, and the vegetation at the side of the road (lower right) into fleeting sunlight in a powerful chiaroscuro that contributes to the melodramatic effect of the illustration as a whole as dark and light compete for dominance in the plate. The effect of the Mahoney wood-engraving is somewhat different. As the closed carriage moves away from the viewer, very little detail about the carriage or the countryside evident is evident because the darkness is so intense. Indeed, the greatest point of interest seems to be the sky and the light-coloured horses to the upper left as Mahoney has thrown the second postillion (holding the whip aloft), the obscured driver, and the passenger with his hand on the window ledge in darkness. In contrast, he shows the back of the first postillion, the road, the guard, several blocks of sawn wood, and the pond (lower centre), at least providing aerial perspective through the sharpness of the foreground and the precision with which Mahoney has described the turning carriage wheels in the centre. William Dorrit's hopes for a better future, his "castle in the air," Mahoney represents as the light on the horizon, upper left, so connected with the right-to-left movement of the horses and carriage that the reader fails to attend to the ominous bank of cloud, upper right. Given the technical limitations of the composite woodblock engraving, Mahoney has achieved a suitably gloomy atmosphere that prepares the reader for William Dorrit's death at the close of the chapter.

In the original serial narrative-pictorial sequence, Phiz focuses not on Mr. Dorrit's hurried return from England but rather upon his mental and physical collapse of the Merdle dinner, An Unexpected After-dinner Speech (II: 19) and then upon his expiring ten days later, with his brother Frederick dying at his bedside in The Night (II: 19), a scene which Mahoney makes the subject of a full-page illustration, the two brothers were before their Father (II: 19), in which Mahoney emphasizes the physical resemblance of William and Frederick Dorrit.

Images of the End of Mr. Dorrit, 1856 through 1910

Left: Phiz's original serial illustration depicting the deaths of the Dorrit brothers, The Night (March 1856: II: 19). Right: Harry Furniss's illustration of Mr. Dorrit's's mental breakdown at the Merdle farewell dinner, Mr. Dorrit Forgets Himself (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's study of a speeding carriage hastening the traveller towards his death in Chapter 55 of "Dombey and Son," On the Dark Road (Part 18: March 1848). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Ch. 12, "Work, Work, Work." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 128-160.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 13 June 2016