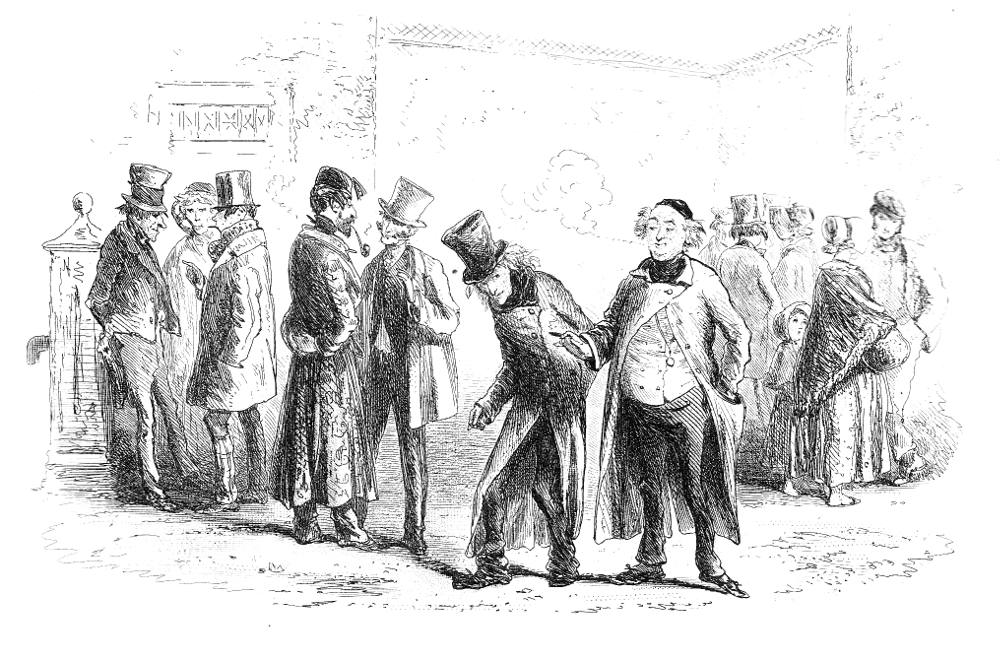

As his hand went up above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's (See page 248), — Book II, chap. 5, is the full title as given in the Chapman and Hall printing. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's thirty-third illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high by 13.7 cm wide, p. 241, framed, under the running head "Mrs. General Called in." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

"Uncle?" cried Fanny, affrighted and bursting into tears, "why do you attack me in this cruel manner? What have I done?"

"Done?" returned the old man, pointing to her sister's place, "where's your affectionate invaluable friend? Where's your devoted guardian? Where's your more than mother? How dare you set up superiorities against all these characters combined in your sister? For shame, you false girl, for shame!"

"I love Amy," cried Miss Fanny, sobbing and weeping, "as well as I love my life — better than I love my life. I don't deserve to be so treated. I am as grateful to Amy, and as fond of Amy, as it's possible for any human being to be. I wish I was dead. I never was so wickedly wronged. And only because I am anxious for the family credit."

"To the winds with the family credit!" cried the old man, with great scorn and indignation. "Brother, I protest against pride. I protest against ingratitude. I protest against any one of us here who have known what we have known, and have seen what we have seen, setting up any pretension that puts Amy at a moment's disadvantage, or to the cost of a moment's pain. We may know that it's a base pretension by its having that effect. It ought to bring a judgment on us. Brother, I protest against it in the sight of God!"

As his hand went up above his head and came down on the table, it might have been a blacksmith's. After a few moments' silence, it had relaxed into its usual weak condition. He went round to his brother with his ordinary shuffling step, put the hand on his shoulder, and said, in a softened voice, "William, my dear, I felt obliged to say it; forgive me, for I felt obliged to say it!" and then went, in his bowed way, out of the palace hall, just as he might have gone out of the Marshalsea room. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 5, "Something Wrong Somewhere," p. 248.

Commentary

The title is somewhat longer in the New York (Harper and Brothers) printing: "It ought to bring a judgment on us. Brother, I protest against it in the sight of God!" As his hand went above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's — Book 2, chap. v. In the original serial illustrations that Phiz provided, this fifth chapter in the second book had no illustration, there being steel-engravings for both Chapters 3 and 6: The Family Dignity is Affronted (Part 11: October 1856) and Instinct Stronger than Training (Part 12: November 1856) respectively, the former illustration involving Fanny Dorrit, her aristocratic-looking father, and the Swiss innkeeper, and the latter the Dorrit sisters, Pet Gowan, Henry Gowan, and Blandois. The present Mahoney illustration realizes the normally timid Frederick Dorrit's indignation at Fanny's supercilious attitude towards her modest, self-sacrificing sister.

Wealth and their new social standing impose certain behavioural constraints upon the Dorrits, including the proper demeanour and attitudes for the young ladies. Consequently, Mr. Dorrit hires a governess of impeccable credentials, Mrs. General, an officer's widow, to inculcate the appropriate upper-middle-class manners, skills, etiquette, and biases in his daughters. Mrs. General's account of Miss Amy to her new employer is not entirely positive as she feels that Amy is not sufficiently assertive — and not sufficiently class-conscious. William Dorrit fears that her demeanour is suggestive of the taint of prison. In the present illustration, the normally retiring, elderly musician Frederick Dorrit stands up for Amy, expressing nothing less than indignation about Tip and Fanny's treatment of their good-hearted, serviceable sister. The other Dorrits think Frederick demented. Thus, Dickens shows the Dorrits are prisoners of their own biases and prejudices, and that, in ignoring questions of degree in favour of human sympathy, Amy is a true Dickensian heroine.

Supporting himself by gripping the chair-back, Frederick rebukes Fanny (right), who breaks down under her uncle's criticism of her recent conduct. William in glasses (left) and Tip with his monocle are astounded, failing to appreciate the truth of Frederick's accusations. Large, ornate oil-paintings in the hotel dining-room imply the opulence of the family's new surroundings, in Italy, as they take breakfast. Amy, of course, cannot be embarrassed by her uncle's spirited defence of her because she has just left the table, accompanied by Mrs. General. Mr. Dorrit (upper left) has just dropped his French newspaper in amazement at his normally shy brother's anguish, suggested by his hair standing up. Miss Fanny is "sobbing and weeping" (248), as in the text,about to protest that she loves and is grateful to Amy: "And only because I am anxious for the family credit" (248) — an interesting phrasing in light of the family's tight finances only recently being relieved.

To quote Fani-Maria Tsigakou,

The travellers of the early nineteenth century included not only learned or leisured aristocrats but also the new wealthy middle classes eager to take their families on a fashionable tour.

Already in the 1850s, however, the true cognoscenti were venturing further abroad, and the growth of railways and the availability of guidebooks made such continental travel far less exclusive than it would have been in the 1830s, when the action of the novel occurs.William Dorrit does not merely wish his daughters and vacuous son to acquire some sophistication and polish from a trip through Switzerland into Italy; he is attempting to re-invent his family as aristocracy, so that later he can introduce himself in London as having come from the Continent, rather than the Marshalsea.

Frederick Dorrit in other 19th c. series of illustration

Phiz's original study of the very different siblings, The Brothers (Part 10: May 1856).

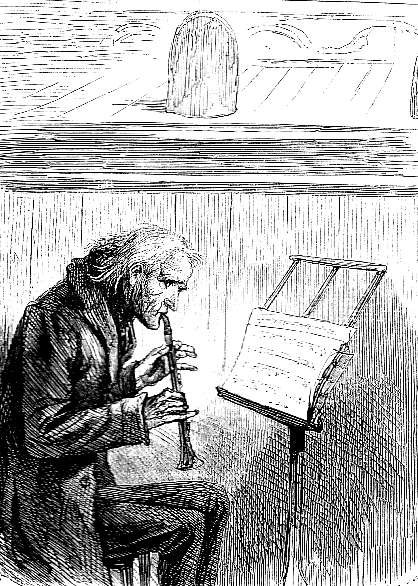

Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's individual study of Amy's clarinet-playing uncle, Frederick Dorrit (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's realisation of Amy's aged uncle, being escorted through the College Yard by his brother, William, The Dorrit Brothers — 1910 lithograph. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's study in the original serial of the Dorrit family's triumphant exit from the debtors' prison, The Marshalsea becomes an Orphan (Part 10, September 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Tsigakou, Fani-Maria. "From the Classical Vision to the Emergence of

Modern Greece (1979)." Victorian Web. Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New

York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. Last modified 9 June 2016