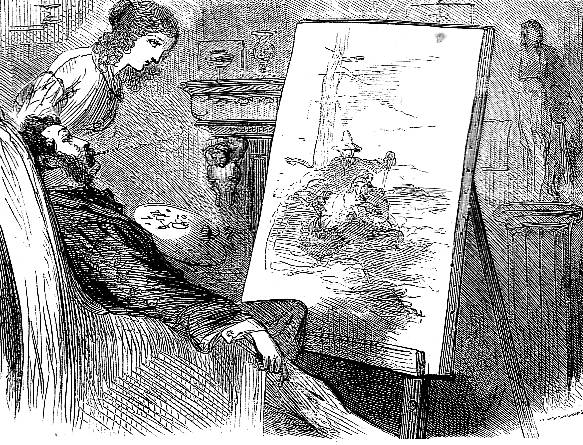

As Arthur Came over the stile and down to the water's edge, the lounger glanced at him for a moment, and then resumed his occupation of idly tossing stones into the water with his foot. (See page 103.) — Book I, chap. 17, "Nobody's Rival," p. 97. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's sixteenth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.6 cm high x 13.7 cm wide. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Before breakfast in the morning, Arthur walked out to look about him. As the morning was fine and he had an hour on his hands, he crossed the river by the ferry, and strolled along a footpath through some meadows. When he came back to the towing-path, he found the ferry-boat on the opposite side, and a gentleman hailing it and waiting to be taken over.

This gentleman looked barely thirty. He was well dressed, of a sprightly and gay appearance, a well-knit figure, and a rich dark complexion. As Arthur came over the stile and down to the water's edge, the lounger glanced at him for a moment, and then resumed his occupation of idly tossing stones into the water with his foot. There was something in his way of spurning them out of their places with his heel, and getting them into the required position, that Clennam thought had an air of cruelty in it. Most of us have more or less frequently derived a similar impression from a man's manner of doing some very little thing: plucking a flower, clearing away an obstacle, or even destroying an insentient object.

The gentleman's thoughts were preoccupied, as his face showed, and he took no notice of a fine Newfoundland dog, who watched him attentively, and watched every stone too, in its turn, eager to spring into the river on receiving his master's sign. The ferry-boat came over, however, without his receiving any sign, and when it grounded his master took him by the collar and walked him into it. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 17, "Nobody's Rival," p. 103.

Commentary

A large, dog (nominally a Newfoundland) and Henry Gowan occupy the foreground; in the background, right, Arthur Clennam is in the process of crossing over a stile. The illustration emphasizes the fashionable nature of the dilettante's dress and his fecklessness, but gives no clue as to Gowan's being an artist — and a snob. Although the story is probably set in the 1830s, Henry Gowan is dressed in the fashionable attire of the the 1860s, a London sophisticate out of place in the rustic setting. Tantalizingly, Mahoney characterizes the diplomat's son by his casual posture and does not reveal Henry Gowan's face, indistinctly reflected in the water at his feet. The moment realised in the story introduces the reader and Arthur Clennam, who has been unofficially engaged to Pet Meagles, to the young aristocrat who has proposed to her, and shortly will carry her off to Italy on their honeymoon.

In the original serial illustrations, in the fifth monthly number (April 1856), Phiz depicts a scene that is significant — the first meeting of Henry Gowan and Arthur Clennam in Chapter 17 (preparing the reader for the scene in Chapter 28 in which Clennam renounces all romantic thoughts of Pet Meagles by ritualistically tossing away the roses that Pet has given him). However, although the full-page illustration sets the rustic scene and establishes a tranquil mood, it does not effectively characterize Henry Gowan and suggest why Clennam takes an instant dislike to him.

Readers may be surprised . . . to find two pleasant landscapes included in Little Dorrit, 'Floating Away' and 'The Ferry'. The view of the ferry at Twickenham, just beyond Richmond Bridge, was one Phiz knew well, and he may even have prepared the sketch while visiting the kindly Moxons at The Lodge. These pictures are all the more surprising because they are found in what Paul Schlicke calls 'The most sombre and oppressive of Dickens's novels . . . organized around a pervasive central symbol of imprisonment.' [p. 339] It seems as though Phiz took the opportunity to let a little fresh air flow through the gloom. — Lester, Chapter 12, "Work, Work, Work," p. 157.

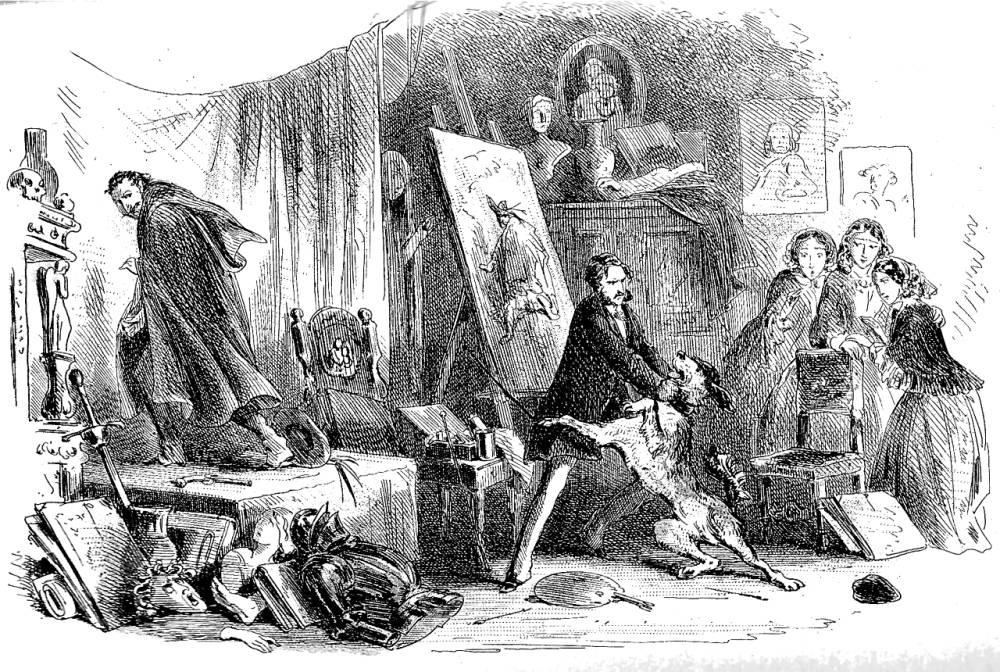

The painterly engraving, a mezzotint, is visually pleasing as a romantic landscape; it fails, however, to advance the reader's understanding of either character, let alone prepare the reader for their adversarial relationship. Although the picturesque upper-Thames setting rather than the diminutive figures of the middle class travellers, Gowan and Clennam, is Phiz's primary interest, Hablot Knight Browne at least depicts Gowan's dog accurately, whereas, despite the intense focus on the indolent Gowan in Mahoney's illustration, the otherwise well realised dog is not a Newfoundland. Although both pictures are realisations of the same textual passage, in the April 1856 version Clennam is standing still, observing the man on the river bank, rather than stepping over a stile — and Gowan is not looking down, his lands in his pockets, but looking off towards the left, presumably to the ferry. And Phiz does not convey a sense of either Gowan's features or listless character here asMahoney does through a representative pose; rather, Phiz waits until the scene in Gowan's studio in Italy, Instinct Stronger than Training (Book 2, ch. 6), to describe the artist's temperament and person.

Henry Gowan in other editions, 1857 to 1910

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's illustration of the Gowans in Henry's studio two months after marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan (1867). Right: Phiz's November 1856 scene of Gowan's brutally commanding his dog, Instinct Stronger than Training (Book 2, Ch. 6). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration of the scene on the upper Thames in which Clennam comes upon a stranger waiting to cross the river, The Ferry (Book I, Ch. 17; April 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 12 May 2016