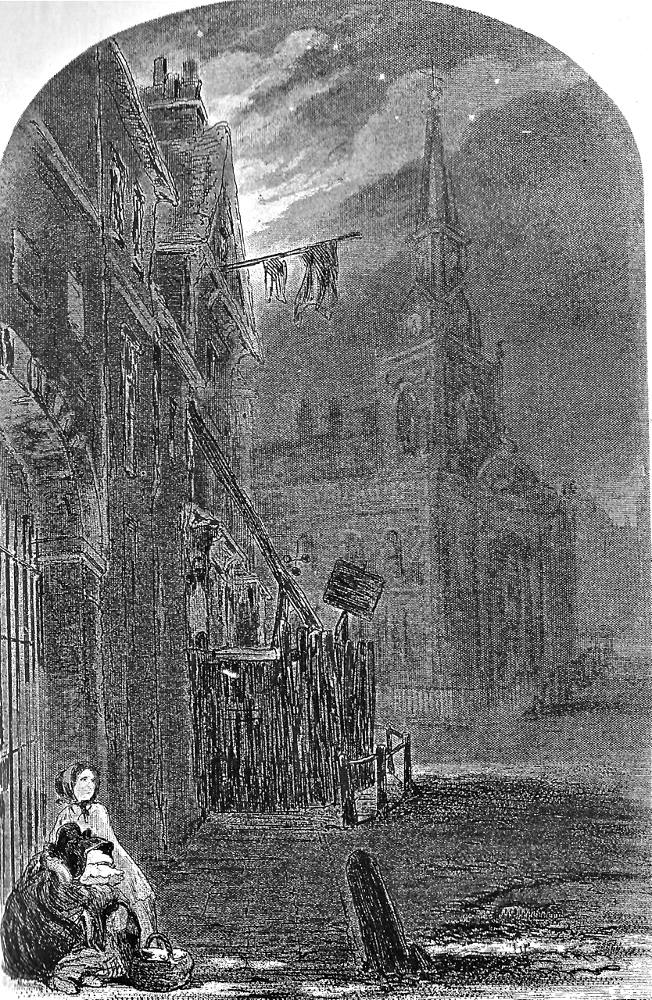

"Little Dorrit." (P. 85), — Book I, chap. 13, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's initial illustration in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition volume of Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 13.3 cm high by 17.8 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Therefore, he sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night, yet not strewing poison on the way by which other men had come to it. That he should have missed so much, and at his time of life should look so far about him for any staff to bear him company upon his downward journey and cheer it, was a just regret. He looked at the fire from which the blaze departed, from which the afterglow subsided, in which the ashes turned grey, from which they dropped to dust, and thought, "How soon I too shall pass through such changes, and be gone!" To review his life was like descending a green tree in fruit and flower, and seeing all the branches wither and drop off, one by one, as he came down towards them. "From the unhappy suppression of my youngest days, through the rigid and unloving home that followed them, through my departure, my long exile, my return, my mother's welcome, my intercourse with her since, down to the afternoon of this day with poor Flora," said Arthur Clennam, "what have I found!" His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer: "Little Dorrit."

[Chapter 14: "Little Dorrit's Party"] Arthur Clennam rose hastily, and saw her standing at the door. This history must sometimes see with Little Dorrit’s eyes, and shall begin that course by seeing him. Little Dorrit looked into a dim room, which seemed a spacious one to her, and grandly furnished. Courtly ideas of Covent Garden, as a place with famous coffee-houses, where gentlemen wearing gold-laced coats and swords had quarrelled and fought duels; costly ideas of Covent Garden, as a place where there were flowers in winter at guineas a-piece, pine-apples at guineas a pound, and peas at guineas a pint; picturesque ideas of Covent Garden, as a place where there was a mighty theatre, showing wonderful and beautiful sights to richly-dressed ladies and gentlemen, and which was for ever far beyond the reach of poor Fanny or poor uncle; desolate ideas of Covent Garden, as having all those arches in it, where the miserable children in rags among whom she had just now passed, like young rats, slunk and hid, fed on offal, huddled together for warmth, and were hunted about (look to the rats young and old, all ye Barnacles, for before God they are eating away our foundations, and will bring the roofs on our heads!); teeming ideas of Covent Garden, as a place of past and present mystery, romance, abundance, want, beauty, ugliness, fair country gardens, and foul street gutters; all confused together, — made the room dimmer than it was in Little Dorrit's eyes, as they timidly saw it from the door. — Book the First, "Poverty," end of Chapter 13, and beginning of Chapter 14, p. 85.

Commentary

The Chapman and Hall woodcut appears later in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition, which instead uses the scene involving the deaths of the Dorrit brothers as the frontispiece: One figure reposed upon the bed, the other kneeling on the floor, drooped over it the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; . . . the two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgments of this world; high above its mists and obscurities. In the New York edition, the caption for this scene at the end of chapter 13 is His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer, "Little Dorrit".

The large-scale, full-page frontispiece enforces a proleptic reading as the passage realised is some eighty-four pages away, when the narrative focus shifts from Arthur Clennam's reverie about his own sad childhood and melancholy upbringing to Little Dorrit's perspective. The large-scale wood-engraving used as the frontispiece in the Harper and Brothers edition of the novel is entirely different; the plate bears the shortened caption in the London edition The two brothers were before their Father, facing p. 334.

After a night at the theatre in company with Maggy, Little Dorrit visits Arthur Clennam in his rooms overlooking Covent Garden to thank him for arranging her brother Tip's release from the Marshalsea. As a consequence of the extra activity after an evening at the working-class theatre where her uncle and sister work, Maggy and Little Dorrit arrive at Maggy's lodging to late to be admitted — everybody in the house is apparently sound asleep, and nobody responds when Amy knocks. This eventuality Little Dorrit had not foreseen, even though she had expected to be locked out of the Marshalsea. Now she and Maggy must make the best of a bad situation and spend the night out on the street, waiting out the five hours before the prison gates open at daybreak. After crossing London Bridge and returning, they notice lights on in the church nearby. The kindly sexton, recalling Amy as appearing in the church's birth registry, offers to let her sleep the few remaining hours of the night in the vestry.

Scenes for "Little Dorrit's Party" in the original, Diamond, and Charles Dickens Library Editions, 1856-1910

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's original March 1856 steel-engraving, the dark plate Little Dorrit's Party. Centre: Eytinge, Junior's dual study of the childlike adult, Maggy, and the apparent child, Amy, locked out of the Marshalsea, Little Dorrit and Maggy (1867). Right: The Harry Furniss realisation of the sexton's giving the stranded pair a room in the nearby St. George's Church, Little Dorrit and Maggy find shelter in a vestry (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1919. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 25 April 2016