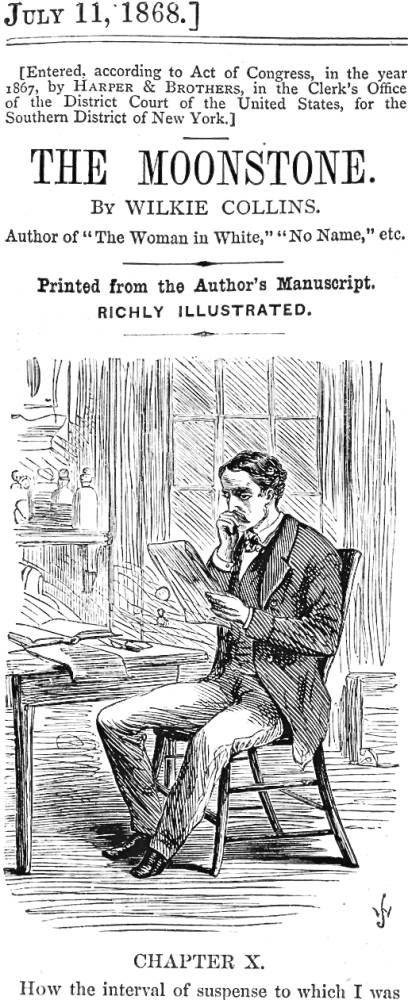

[Franklin Blake, reading Ezra Jenning's notes about Dr. Candy's feverish ravings] — Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance: "Second Period, Third Narrative, Contributed by Franklin Blake," uncaptioned headnote vignette for Chapter X, the twenty-fourth such vignette in the twenty-eighth instalment in Harper's Weekly (11 July 1868), page 437 (page 186 in volume). Wood-engraving, 8.0 x 5.6 cm., located at the head of the tenth chapter. [The vignette is unusual in that it is actually signed conspicuously "W.J.," that is, by William Jewett, one of Harper & Bros. senior illustrators. The physical setting is perfectly consistent with the details of Jennings' study as realised in "I found Ezra Jennings ready and waiting for me", facing the vignette in the first volume edition and sharing the page with it in the serial. Whereas Blake reads with rapt attention and some puzzlement (as suggested by his gesture with his free hand), Ezra Jennings seems seized by despondency as he cannot continue writing.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The serial illustrations appear courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passages suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Twenty-Eighth Instalment

I found Ezra Jennings ready and waiting for me.

He was sitting alone in a bare little room, which communicated by a glazed door with a surgery. Hideous coloured diagrams of the ravages of hideous diseases decorated the barren buff-coloured walls. A book-case filled with dingy medical works, and ornamented at the top with a skull, in place of the customary bust; a large deal table copiously splashed with ink; wooden chairs of the sort that are seen in kitchens and cottages; a threadbare drugget in the middle of the floor; a sink of water, with a basin and waste-pipe roughly let into the wall, horribly suggestive of its connection with surgical operations—comprised the entire furniture of the room. The bees were humming among a few flowers placed in pots outside the window; the birds were singing in the garden, and the faint intermittent jingle of a tuneless piano in some neighbouring house forced itself now and again on the ear. In any other place, these everyday sounds might have spoken pleasantly of the everyday world outside. Here, they came in as intruders on a silence which nothing but human suffering had the privilege to disturb. I looked at the mahogany instrument case, and at the huge roll of lint, occupying places of their own on the book-shelves, and shuddered inwardly as I thought of the sounds, familiar and appropriate to the everyday use of Ezra Jennings’ room.

"I make no apology, Mr. Blake, for the place in which I am receiving you," he said. "It is the only room in the house, at this hour of the day, in which we can feel quite sure of being left undisturbed. Here are my papers ready for you; and here are two books to which we may have occasion to refer, before we have done. Bring your chair to the table, and we shall be able to consult them together."

I drew up to the table; and Ezra Jennings handed me his manuscript notes. They consisted of two large folio leaves of paper. One leaf contained writing which only covered the surface at intervals. The other presented writing, in red and black ink, which completely filled the page from top to bottom. In the irritated state of my curiosity, at that moment, I laid aside the second sheet of paper in despair. — "Second period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) Third Narrative. Contributed by Franklin Blake," Ch. 10, p. 437.

Commentary

The serial instalment for 11 July 1868 uses a headnote vignette that complements the main illustration: seated after his two-hour separation from Jennings, Franklin Blake reads the physician's notes, whereas in the main illustration ("I found Ezra Jennings ready and waiting for me."), the innovative physician is about to ask Blake highly specific questions about his physical state a year before and jot down his responses in an attempt to understand Blake's apparent sleepwalking. The act of reading is once more identified as a central part of the detective's task, whether it be reading characters' motives, or postures, or documents. The implication is, then, that, just as Franklin Blake is playing the role of investigator here, so, too, the text has thrust upon the reader the role of detective, foregrounding the central and complementary roles of reading and writing in the narrative as a whole:

Heightening this motif of interpretation, the Harper's illustrations also call attention to acts of reading. This visual pattern underlines the letterpress's focus on the interpretation of narrative, the "battle over whose perspective and voice" prevail in the novel. In a series of repetitive images, the illustrations show Cuff, then both Blake and Jennings, all reading (Part 12; Part 28, fig. 8). These scenes of characters immersed in books create self-reflexivity around the reading process itself, reminding us forcefully that The Moonstone requires its characters as well as its readers to become active analysers of narratives, their biases, and visual as well as verbal points of view. — Leighton and Surridge, p. 224.

Whereas literary texts such as this novel are produced for public consumption and, in the case of a story serialised in Harper's Weekly, may reach a readership in excess of 100,000, very private notes are written in equally private rooms (as, for example, Rosanna Spearman's notes to Franklin Blake) for extremely limited consumption. Here, however, the clinical notes of Ezra Jennings, intended only for his own reference as they constitute a professional document about another individual's health, are in the hands of a concerned third party. "The novel's illustrations similarly remind us of how documents are produced and by whom, repeatedly representing the act of writing and the conditions of producing documents. . . . The visual text is thus highly self-conscious about hermeneutic activity and the reading of verbal and visual texts" (Leighton and Surridge, p. 224). Here, the illustrator, William Jewett, in this is a rare instance of a signed headnote vignette invites the reader to compare Blake's outward demeanour as a reader with the mental process of reading which Collins describes in the text. Certainly Jewett suggests here that reading such notes is a privilege conferred upon Franklin Blake out of Jennings' concern for Blake's mental and physical health since these medical records are held in strictest confidence to protect Dr. Candy.

As a progressive physician, Jennings emphasizes developing an informed diagnosis over simply delivering traditional remedies and conventional cures. For example, he questions Franklin Blake carefully about his state of health on the night of the diamond's disappearance (undoubtedly pointed in that direction by Dr. Candy's incoherent ramblings):

"Pardon me. Anything is worth mentioning in such a case as this. Betteredge attributed your sleeplessness to something. To what?"

"To my leaving off smoking."

"Had you been an habitual smoker?"

"Yes."

"Did you leave off the habit suddenly?"

"Yes."

"Betteredge was perfectly right, Mr. Blake. When smoking is a habit a man must have no common constitution who can leave it off suddenly without some temporary damage to his nervous system. Your sleepless nights are accounted for, to my mind. My next question refers to Mr. Candy. Do you remember having entered into anything like a dispute with him — at the birthday dinner, or afterwards — on the subject of his profession?"

Jennings then considers how Candy was able to administer the draught of laudanum without Blake's being aware that he was taking it. The answer appears to be Godfrey Ablewhite when he gave Franklin his after-dinner brandy. Thus, the papers that Franklin Blake begins to read earlier in the chapter become important later in the chapter, the reading of which at this advanced stage of the conversation may well be the subject of the headnote vignette, clearly situated in Dr. Jennings' office:

"Mr. Blake," he said, "if you read those notes now, by the light which my questions and your answers have thrown on them, you will make two astounding discoveries concerning yourself. You will find — First, that you entered Miss Verinder's sitting-room and took the Diamond, in a state of trance, produced by opium. Secondly, that the opium was given to you by Mr. Candy — without your own knowledge — as a practical refutation of the opinions which you had expressed to him at the birthday dinner."

I sat with the papers in my hand completely stupefied. — "Second period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) Third Narrative. Contributed by Franklin Blake," Ch. 10, p. 438.

The volume edition sharpens the juxtaposition of what was the weekly instalment's large-scale illustration, "I found Ezra Jennings ready and waiting fior me" (p. 187 in volume) and the headnote vignette immediately opposite (p. 186). The juxtaposition, for example, emphasizes that both are seated at writing desks, that Franklin Blake is thoughtfully reading, and that Ezra Jennings is pausing in thought as he writes. Thus, William Jewett is reflecting in the complementary illustrations on the cerebral processes involved in reading and writing — the latter activity requiring both time for contemplation and "food for thought" (including the open volume at the writer's feet and the hand-written pages on the floor behind him).

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the "quiet English home" in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F.A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946).

- Bibliography for both Primary and Secondary Sources for The Moonstone and British India (1868-2016)

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations by William Jewett. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August 1868, pp. 5-529.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone. With 19 illustrations. The Works of Wilkie Collins. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900. Volumes 6 and 7.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Lonoff, Sue. Chapter 7, "The Moonstone and Its Audience." Wilkie Collins and His Readers: A Study of the Rhetoric of Authorship. New York: AMS Press, 1982. Pp. 170-230.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 1 December 2016

Last updated 26 October 2025