Scrooge Patting Children.

Charles Green

c. 1912

14.8 x 10.9 cm. vignetted,full-page

Dickens's A Christmas Carol, The Pears' Centenary Edition of The Christmas Books, vol. 1, page 134.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

He went to church, and walked about the streets, and watched the people hurrying to and fro, and patted children on the head, and questioned beggars, and looked down into the kitchens of houses, and up to the windows, and found that everything could yield him pleasure. He had never dreamed that any walk — that anything — could give him so much happiness. In the afternoon he turned his steps towards his nephew's house. ["Stave Five: The End of It," p. 133]

Commentary

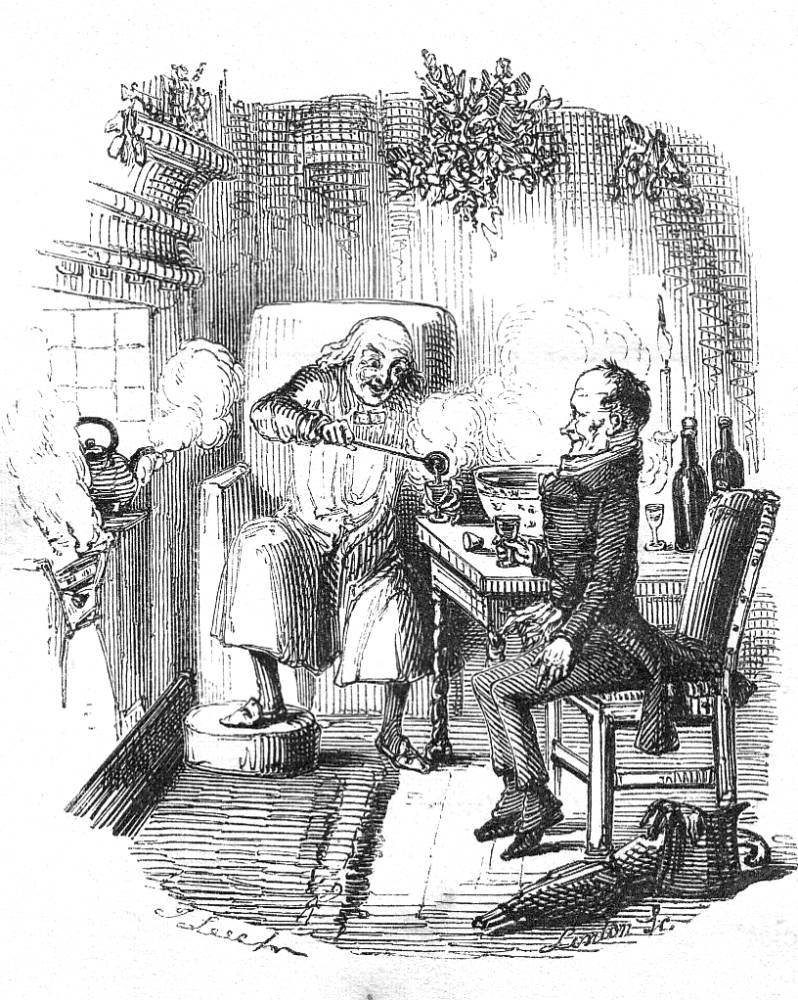

The third of the five scenes that Green has included for the final stave is a large-scale vignette (following Dickens's description of Scrooge's uncharacteristic behaviour) that shows how profoundly the visitations have affected Scrooge, who has gone to church and taken pleasure from exploring how his neighbours celebrate Christmas. His new attitude towards the rest of humanity is signalled by his interacting with children, beginning with the boy passing his house, dressed for church in his "Sunday clothes" (129). Punch cartoonist John Leech provided only a single image of the post-visitation Scrooge, but Green, with a much longer program of illustration (thirty-one illustrations versus the 1843 edition's eight), feels that he can best describe the spiritual state of the redeemed Scrooge by showing how he now relates to children: the boy in the street before the church service, the little girl in the pinafore after church, and around dinner time his sister's boy, Fred.

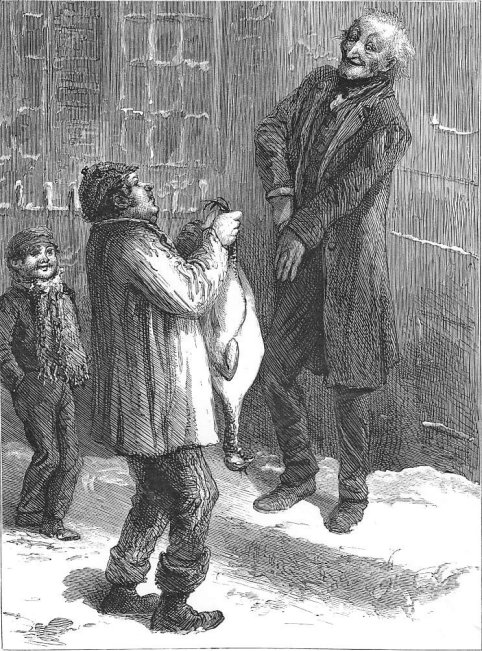

The original illustrator, John Leech, included just one small wood-block engraving to demonstrate Scrooge's change of heart as an employer, Scrooge and Bob Cratchit, or The Christmas Bowl, but, of the other nineteenth-century illustrators of the novella, only Sol Eytinge, Junior in the 1868 Ticknor and Fields edition has devoted a significant proportion of his program to the new, improved Scrooge, showing him with child-like glee putting on his socks on Christmas morning and smiling broadly as he digs into his pocket to find the coins to pay the poulterer's man for the prize bird he intends to send anonymously to the Cratchits in The Prize Turkey. Green utilizes the detailing of the wrought-iron area and garden railings, the snowy street marked with the prints of feet and carriage tracks, and Scrooge's own door in the background to convince us of the reality of the new behaviour that signals Scrooge's social re-integration. The child for her part seems a little uncomfortable about being thus acknowledged, but Scrooge seems to be genuinely enjoying himself as, having donned the kind of clothing he wears to his place of business, he walks "abroad among his fellow man" (36), as Jacob Marley indicated is the obligation of every human being, for now mankind is his business.

Images from the original (1843), the Ticknor & Fields (1867), and American Household Editions (1876) of the Reformed Scrooge

Left: John Leech's tailpiece of Scrooge and his employee sharing punch, Scrooge and Bob Cratchit, or The Christmas Bowl. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's attempt to capture the reformed Scrooge's child-like ebullience, The Prize Turkey.

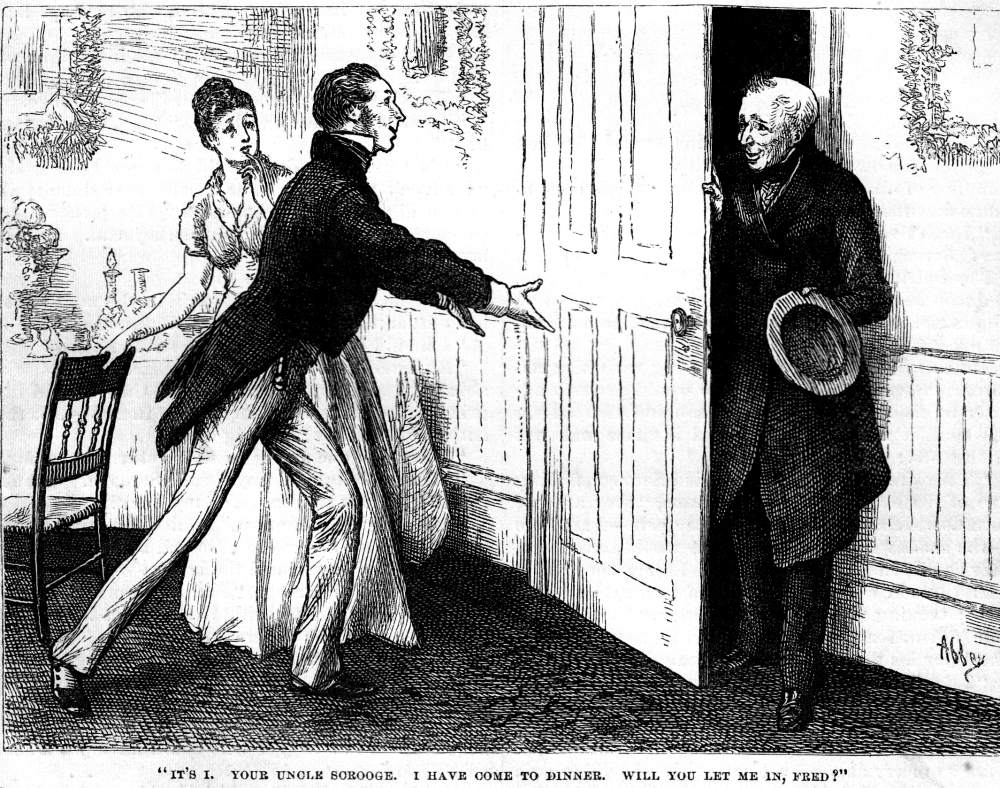

Above: E. A. Abbey's 1876 engraving of Scrooge's "mending fences" with his nephew, "It's I. Your Uncle Scrooge! I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?" [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol. With 27 illustrations by Charles Green, R. I. Pears' Christmas Annual. London: A & F Pears, 1892.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Victorian

Web

Illustration

Charles

Green

A Christmas

Carol

Next

Last modified 30 August 2015