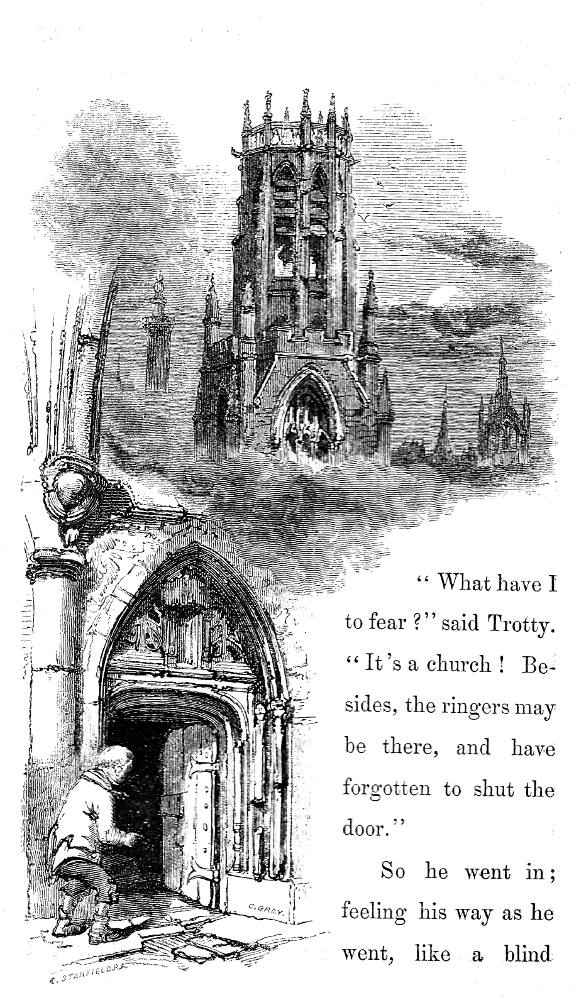

The Tower of the Chimes

Charles Green

c. 1912

14 x 11.2cm vignetted

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, vol. 2 title-page.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Green —> Next]

The Tower of the Chimes

Charles Green

c. 1912

14 x 11.2cm vignetted

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, vol. 2 title-page.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

For the night-wind has a dismal trick of wandering round and round a building of that sort, and moaning as it goes; and of trying, with its unseen hand, the windows and the doors; and seeking out some crevices by which to enter. And when it has got in; as one not finding what it seeks, whatever that may be, it wails and howls to issue forth again: and not content with stalking through the aisles, and gliding round and round the pillars, and tempting the deep organ, soars up to the roof, and strives to rend the rafters: then flings itself despairingly upon the stones below, and passes, muttering, into the vaults. Anon, it comes up stealthily, and creeps along the walls, seeming to read, in whispers, the Inscriptions sacred to the Dead. At some of these, it breaks out shrilly, as with laughter; and at others, moans and cries as if it were lamenting. It has a ghostly sound too, lingering within the altar; where it seems to chaunt, in its wild way, of Wrong and Murder done, and false Gods worshipped, in defiance of the Tables of the Law, which look so fair and smooth, but are so flawed and broken. Ugh! Heaven preserve us, sitting snugly round the fire! It has an awful voice, that wind at Midnight, singing in a church!

But, high up in the steeple! There the foul blast roars and whistles! High up in the steeple, where it is free to come and go through many an airy arch and loophole, and to twist and twine itself about the giddy stair, and twirl the groaning weathercock, and make the very tower shake and shiver! High up in the steeple, where the belfry is, and iron rails are ragged with rust, and sheets of lead and copper, shrivelled by the changing weather, crackle and heave beneath the unaccustomed tread; and birds stuff shabby nests into corners of old oaken joists and beams; and dust grows old and grey; and speckled spiders, indolent and fat with long security, swing idly to and fro in the vibration of the bells, and never loose their hold upon their thread-spun castles in the air, or climb up sailor-like in quick alarm, or drop upon the ground and ply a score of nimble legs to save one life! High up in the steeple of an old church, far above the light and murmur of the town and far below the flying clouds that shadow it, is the wild and dreary place at night: and high up in the steeple of an old church, dwelt the Chimes I tell of. pp. 18-19, 1912 edition]

Charles Green wasone of the original 1870s Household Edition illustrators for Chapman and Hall — his commission was new wood-engravings for The Old Curiosity Shop (1876). Hehad undoubtedly studied the limited program of wood-engravings that Fred Barnard executed in 1878 for The Christmas Books, but probably did not see the pair of illustrations that Edwin Austin Abbey provided for The Chimes in the American Household Edition volume entitled Christmas Stories, published by Harper and Brothers in 1876. Whereas the 1844 volume contains thirteen wood-engravings, many dropped into the letterpress, Charles Green almost seventy years later had a much more extensive commission, thirty lithographs. And whereas only one of the 1844 plates conveys the ghostly atmosphere of the old church — Clarkson Stanfield's architectural study The Old Church, Green shows the goblins swirling about the tower in the title-page vignette, then followsup with the small-scale The Home of the Bells, showing a Gothic spire by moonlight, and then indulges in a riotous fantasy of cavorting, semi-nude female sprites (hardly "goblins")and hideous, shrunken male goblins The Goblins of the Bells. The squared top of the bell-tower in the title-page vignette is consistent with the earlier Stanfield and Doyle treatments in the original series, whereas Green shows a spire surmounting the squared tower The Home of the Bells. The original plates emphasize the Gothic lantern tower, modelled on that of old Saint Dunstan's-in-the-West, but are otherwise less atmospheric than Green's, because in Doyle's and Stanfield's treatments the architectural setting in London either complements or subordinates the real, human figures associated with the church steps in the story.

Green's treatment of the subject as it once more realistic and three-dimensional than that of his predecessors — and more fanciful in the early introduction of the comic goblins. Of particular interest, however, is the hooded figure (bottom centre) at whose shroud the goblins tug, as if to reveal what lies beneath. The scowling figure recalls Leech's The Last of the Spirits in A Christmas Carol, and likely represents the pessimistic vision of the future (or a future) that Trotty encounters in the bell tower. Complementing this enigmatic figure is the owl (left), who is both literal (a denizen of the night) and symbolic — that is, suggestive of the underlying truths that Trotty discovers about the essential inhumanity of the authorities, Cute and Bowley. Huddled about the mediaeval tower, suggestive of the feudal and religious past, are the lowly dwellings of the London poor in the midst of the Hungry Forties, the days still recalled by the tale in its 1912 iteration.

The tower of St. Dunstan's-in-the-West on Fleet Street, long a landmark, disappeared with the demolition of the old church in 1830-32 intended to facilitate the widening of Fleet Street. The rebuilding of the church, accomplished by 1842, included a square tower with an octagonal lantern in the neo-Gothic style, resembling those of St. Botolph's in Boston and St. Helen's in York (perhaps modelled on an actual Gothic lantern at Ely Cathedral). The form of the lantern might have been immediately inspired by that of St. George's Church in Ramsgate, built in 1825. Dickens does not mention the old church's associations with John Donne, William Tyndale, and Sir Isaac Walton, but in calling St. Dunstan's simply "The old church" the writer is establishing the chronological setting as pre-1830, even though Will Fern, a radical from Dorset, is clearly a contemporary figure of working-class and agrarian rebellion.

Left: Clarkson Stanfield's atmospheric rendering of The Old Church. Right: Richard Doyle's miniature ofthe Gothic bell-tower, The Dinner on the Steps.

E. A. Abbey's 1876 wood-engraving of Trotty's terrifying dream-vision, What Trotty saw in the Belfry.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes. Introduction by Clement Shorter. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Pears' Centenary Edition. London: A & F Pears, [?1912].

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated byFred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Reynolds, H. The Churches of the City of London. London: Bodley Head, 1922.

Last modified 27 March 2015