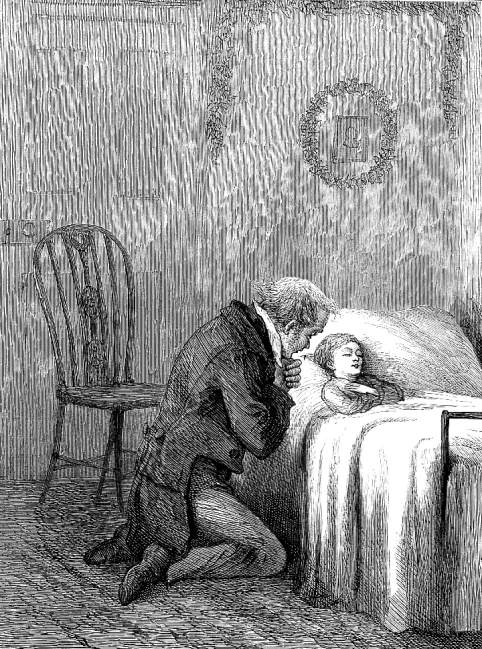

"Philip's Favourite Son in a Bad Way" by Charles Green. 1912. 7.5 x 9 cm, vignetted. Dickens's The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas Time, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the short titles given in the "List of Illustrations" (15-16). For example, the actual illustration has beneath it a direct quotation that illustrates the dire nature of dissolute gambler George Swidger's dire medical condition, "The Chemist, whiter than the dying man, appeared before him. Obedient to the motion of his hand, he sat upon the bed" (111, quoted from the page opposite).

The Context of the Illustration

"My time is very short, my breath is shorter," said the sick man, supporting himself on one arm, and with the other groping in the air, "and I remember there is something on my mind concerning the man who was here just now, Father and William — wait! — is there really anything in black, out there?"

"Yes, yes, it is real," said his aged father.

"Is it a man?"

"What I say myself, George," interposed his brother, bending kindly over him. "It's Mr. Redlaw."

"I thought I had dreamed of him. Ask him to come here."

The Chemist, whiter than the dying man, appeared before him. Obedient to the motion of his hand, he sat upon the bed.

It has been so ripped up, to-night, sir," said the sick man, laying his hand upon his heart, with a look in which the mute, imploring agony of his condition was concentrated, "by the sight of my poor old father, and the thought of all the trouble I have been the cause of, and all the wrong and sorrow lying at my door, that —"

Was it the extremity to which he had come, or was it the dawning of another change, that made him stop?

"— that what I can do right, with my mind running on so much, so fast, I'll try to do. There was another man here. Did you see him?"

Redlaw could not reply by any word; for when he saw that fatal sign he knew so well now, of the wandering hand upon the forehead, his voice died at his lips. But he made some indication of assent. ["Chapter Two: The Gift Diffused," Pears Centenary Edition, 110-11]

Commentary: Another Death-bed Scene

Right: Robert Seymour's celebrated study of the dying alcoholic entertainer from the framed tale in The Pickwick Papers, The Dying Clown (April 1836).

Charles Green’s 1895 illustration, which was eventually published in the Pears Centenary Edition of The Haunted Man (1912), seems to respond directly to the text rather than to the 1848 first edition illustrations. In fact, Green's illustration here has no visual antecedent in the various nineteenth-century editions of The Haunted Man. Consequently, Green's conception strikes the reader as at once his own and yet derivative since he had many a death-bed illustration from Dickens's works to draw upon, including his own of Richard ("The Back Attic") in The Chimes.

As a set piece, the death-bed scene had been a standard since the Middle Ages, when adying saint or the dead Christ would be the subject of group lamentation; moreover, in the Dickens canon, ever since the short story "The Dying Clown" appeared had in the third chapter of Pickwick Papers (1836-37), such scenes enabled the writer to evoke in the reader a highly sentimental response, whether the tender feeling were entirely merited or not. Thus, this scene has visual and textual antecedents, including Seymour's The Dying Clown in Pickwick and, in The Christmas Books, the death of the back attic in The Chimes, and that even more pathetic demise of Tiny Tim (see below) in A Christmas Carol, that undoubtedly affected Green's handling and choice of composition for the final illustration in "The Gift Diffused."

Whereas in the text Redlaw reacts with shock and surprise that the street boy has led him to the dying George Swidger in an East End slum, in the illustration he seemsdignified and sympathetic as he stares into the face of the dying wastrel — a man ofabout his own age, and therefore a memento mori. Redlaw sits on the bed as bidden, as George lays his hand upon his heart as he begins to utter his final words, which betray the baleful influence of the Chemist's doppelganger. Old Philip, George's father, stoops near George's head, presumably to hear more clearly his son's final utterance, while the college's butler, William Swidger, watches from behind (upper left). Green makes his principal figures the dissolute gambler and the solicitous chemist: horizontal George in his white night-shirt, covered by white sheets and coverlet, contrasting the black-clad, vertical Redlaw, positioned to observe closely the baneful effect of the loss of memory and sentiment in the now unrepentant "reckless, ruffianly, and callous" gambler, and in his aged father, who, influenced by Redlaw's Phantom, too, disowns George as "no son of mine" (112). Thus, the tranquil death-bed scene as realised by Green explodes into vituperation and recrimination moments later in the text.

Nineteenth-Century Deathbed Illustrations from Dickens Works

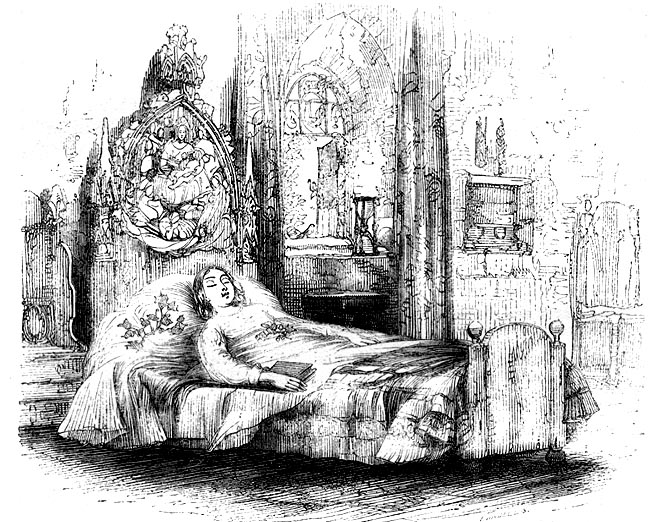

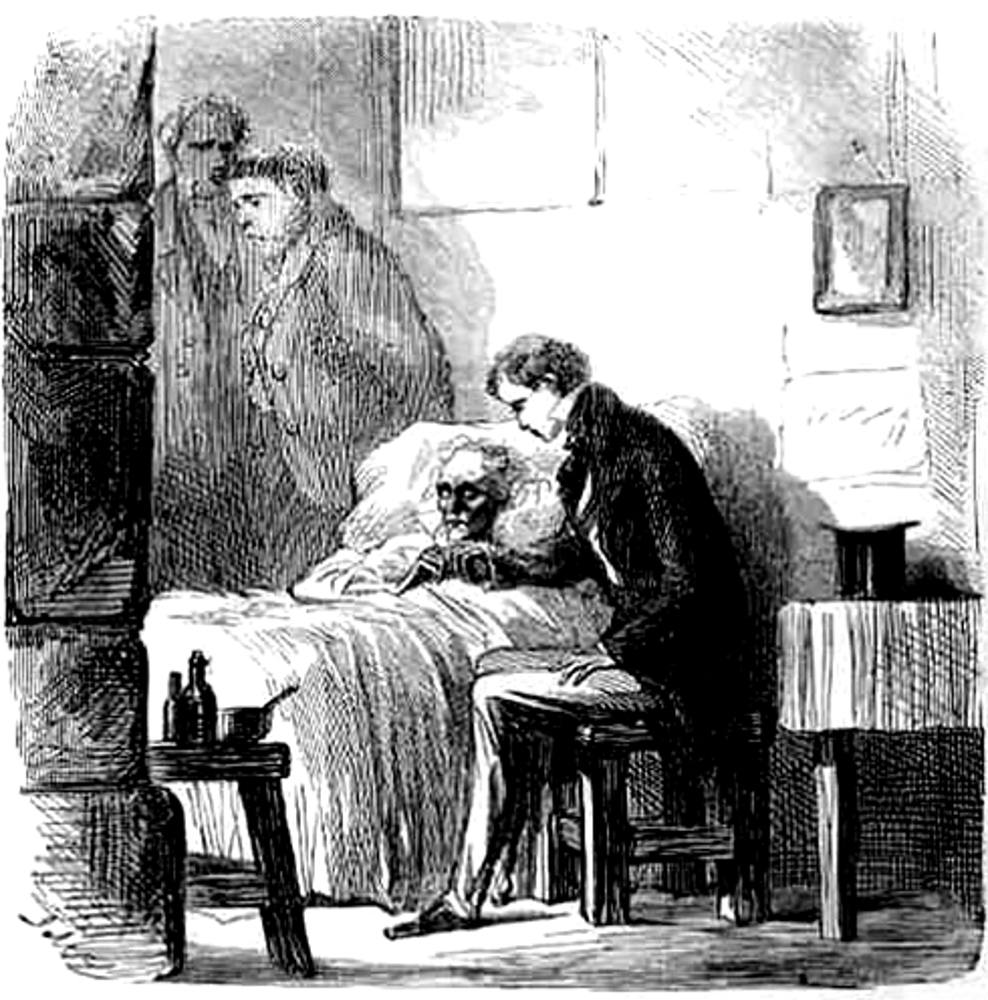

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s excessively sentimental depiction of the imagined death of the endearing Cratchit child with a manifest handicap and a cheerful spirit, "Poor Tiny Time!" (1868). Centre: George Cattermole's celebrated illustration of the beatific heroine of The Old Curiosity Shop, At Rest (Nell dead) (30 January 1841). Right: John Mclenan's sombre treatment of the death of Magwitch in Great Expectations, The placid look at the white ceiling came back, and passed away, and his head dropped quietly on his breast. (27 July 1861).

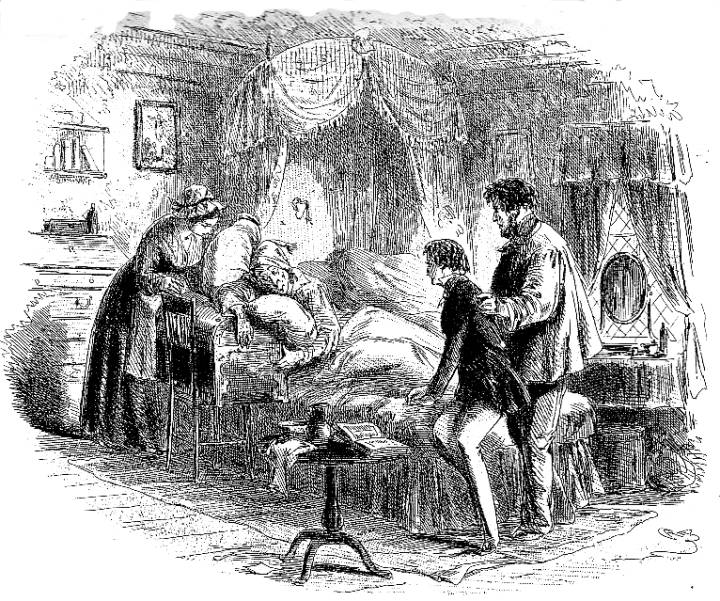

Above: Hablot Knight Brown's parodic treatment of the standard death-bed scene in David Copperfield, I find Mr. Barkis "going out with the tide" (February 1850).

Above: Green's realisation of the pathetic death of Richard in Trotty's apocalyptic vision in The Chimes, The Death Bed (1912).

Illustrations for the Other Volumes of the Pears' Centenary Christmas Books of Charles Dickens (1912)

Each contains about thirty illustrations from original drawings by Charles Green, R. I. — Clement Shorter [1912]

- A Christmas Carol (28 plates) Vol. I (1892)

- The Chimes (31 plates) Vol. II (1894)

- L. Rossi's The Cricket on the Hearth (22 plates) Vol. III (1912)

- The Battle of Life (28 plates) Vol. IV (1893)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man; or, The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

_____. The Haunted Man. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1848). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. II, 235-362, and 365-366.

_____. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas Time. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. (1895). London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_____. The Haunted Man. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Felix Octavius Carr Darley. The Household Edition. New York: James G. Gregory, 1861. II, 155-300.

Created 4 September 2015

Last modified 10 April 2020