This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added captions and links. Click on the images for larger pictures and bibliographic information where available.

This volume was conceived as the accompanying catalogue for a major exhibition which the Guildhall Art Gallery (London) hosted from 29 April to 29 August 2011. Boasting a splendid collection of Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian paintings, the Guildhall has already organised several fascinating shows which contributed to the rediscovery of nineteenth-century British artists: William Powell Frith in 2006-2007, George Frederick Watts in 2008-2009 (Atkinson Grimshaw is currently being honoured by that institution). Sir John Gilbert (1817-1897) is now mainly remembered — when he is at all — as an illustrator. He is said to have produced some 30,000 drawings for the Illustrated London News, a staggering figure even if one takes into account its obvious exaggeration. In 1893, Gilbert decided to distribute his paintings among the recently established municipal art museums. This gift to the nation largely benefited the Guildhall Art Gallery, which now holds one of the largest collections of Gilbert's work. As Head of the gallery, Vivien Knight quite logically decided to put on an exhibition around a largely forgotten artist.

In their Introduction, Vivien Knight and Assistant Curator Naomi Allen claim that "nothing substantial has been published on [Gilbert] since his death" (11). Thanks to the book published by Lund Humphries, we now have a more than substantial volume about a Victorian petit maître who may not necessarily come back in fashion in the near future. In his lifetime, Gilbert was nicknamed "the Walter Scott of Painting", and he might well prove as definitely outmoded as the author of The Heart of Midlothian, and for the same reasons. As a painter, he was mainly interested in the past, creating historical scenes like Cardinal Wolsey, Chancellor of England, on his Progress to Westminster Hall, or battle scenes like The Morning of the Battle of Agincourt. Even towards the end of the nineteenth century it was generally felt that Gilbert had somewhat outstayed his welcome, and the works he exhibited in his later career were poorly received.

After a "biographical sketch" by Vivien Knight and Mark Bills, and an evocation of Blackheath, the artist's native town, by Neil Rhind, two chapters are devoted to the activity which allowed Gilbert to conquer fame: illustration. Paul Goldman, an eminent specialist of the so-called Golden Age of Victorian illustration, studies the "Master of historical romance", that is, Gilbert as a book illustrator. On that subject, it proves fascinating to compare what Goldman has to say with what was written about Gilbert by Stuart Sillars in The Illustrated Shakespeare 1709-1875 (2008). While the hero of the present book turns out to have been no more than a secondary figure in Sillars's book, Paul Goldman does acknowledge the weaknesses and the limitations of his subject but he also underlines his strengths. For Sillars, "The work of Gilbert [and other minor illustrators] can never equal such technical complexity and rich suggestions of mood, often ambiguous and disturbing [as one finds in the drawings of Pre-Raphaelite artists]" (Sillars 320), a judgment echoed by Goldman: "He is not in the same league as the Pre-Raphaelites [...] for he exhibits neither their intellectual depth nor their rigour" (95). Goldman wonders whether Gilbert's Shakespeare (some 800 illustrations) was a monument of a heroic failure: the artist was "at his best with the coarse rather than the lyrical" (88), he was excellent at historical episodes and war scenes, which makes him "the Errol Flynn of mid-nineteenth-century illustration" (95)!

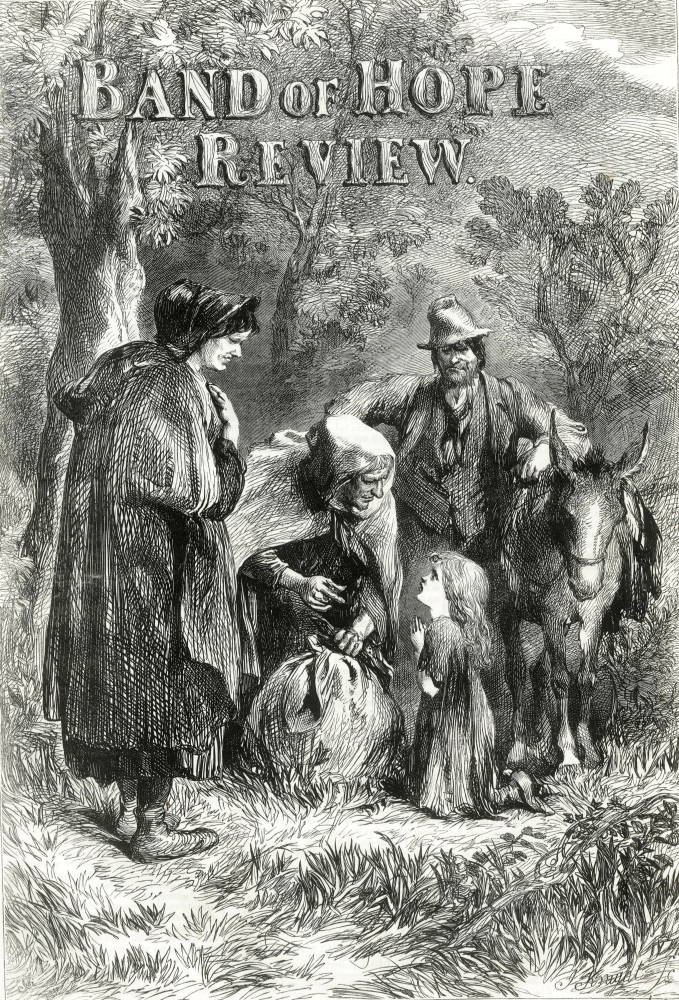

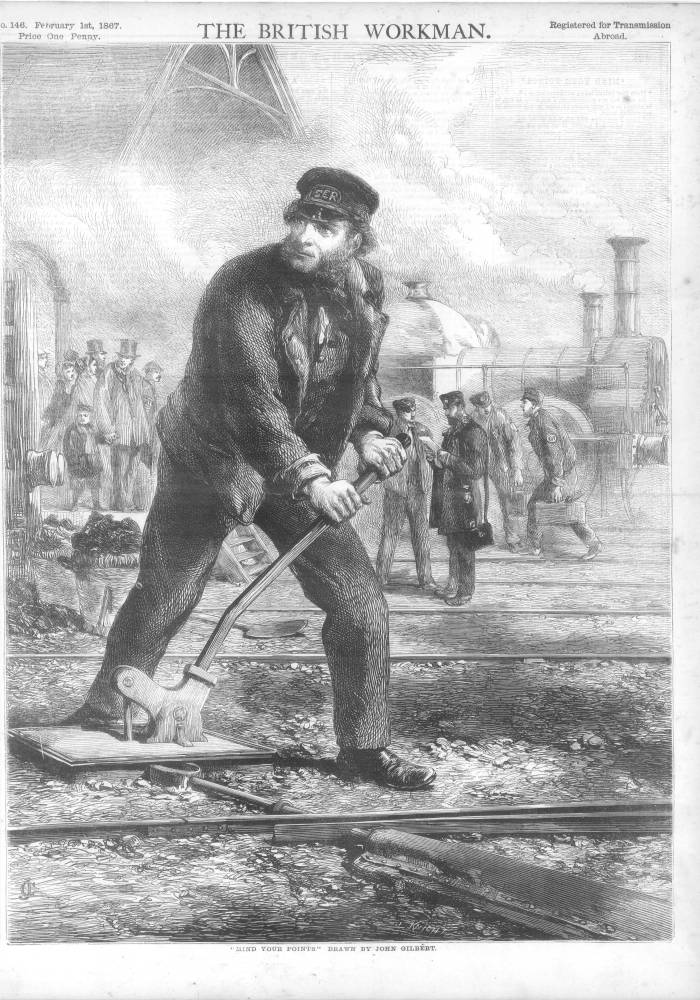

Two front cover illustrations for periodicals by Gilbert. Left: "Curious Jane with the Gypsies," for the front cover of the Band of Hope Review (1862). Right: "Mind Your Points," for the British Workman (1867).

Mark Bills then examines Gilbert's work for the pictorial press, which introduced "a distinctive character to the illustration of news" according to Mason Jackson (The Pictorial Press: Its Origin and Progress, 1885: 355). Gilbert worked for The Illustrated London News right from the very first number of the magazine, released on 14 May 1842, and he remained that paper's principal illustrator for thirty years; his collaboration with Punch was less sustained, as a sense of humour was not one of his dominant qualities. While he was generally commissioned to depict real events, "Gilbert chose to work from the imagination rather than from life. Yet what his art lost in veracity it gained in freedom of design" (106).

Timothy Wilcox focuses on Gilbert's relation with the Royal Watercolour Society, as a Member from 1852 to 1871, and then as President from 1871 until his death. His election reflected "a shift in the cultural landscape and capitalis[ed] on reputations that had already been secured through other media" (121). His watercolours catered for "the newly literate middle classes['] vast appetite for English history" (122). In the following chapter, Nicola Bown provides the cultural context for what could well become Gilbert's most enjoyable picture for today's audiences: The Enchanted Forest (1886), showing two medieval knights on horseback, surrounded by all sorts of goblins and spirits. Since the extremely successful exhibition which the Royal Academy dedicated to Victorian Fairy Painting in 1997-98, we have witnessed a revival of a whole subgenre whose only representatives to be remembered till then were Richard Dadd and Joseph Noel Paton. Nicola Bown suggests interesting parallels with George MacDonald's "faerie romance" Phantastes (1856), and compares Gilbert's watercolour with works by Maclise, Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale, Burne-Jones or Richard Doyle.

Detail from the front cover picture of the book, Fair St George (1881), in the Guildhall Gallery's permanent collection, showing the "billowing drapes" that Gilbert found so useful.

Taking a path already trodden in relation to such geniuses as Turner or Picasso, Kathleen Froyen focuses on "Sir John Gilbert and the Old Masters". The "English Rubens" was a great admirer of Rembrandt, whose textures he tried to imitate, using few pigments, which must have darkened over time. An autodidact without any formal training, Gilbert often hid his figures under billowing drapes; "the Commentators were so impressed by the vigour and inventiveness of Gilbert's art that they were almost always willing to forgive him his faults. His enthusiasm made up for his lack in schooling and insufficient study of nature" (156).

This chapter leads the reader to the technical part of the book: four shorter chapters are devoted to the material aspects of Gilbert's art. Spike Bucklow studies the various types of paint used by the artist and his capabilities as "London's most prolific draughtsman over this period" (186). Libby Sheldon explores "Gilbert's ordinary and extraordinary uses of watercolour and gouache technique," the use of bodycolour being one of Gilbert's tricks to make his watercolours look like oil paintings. Caroline Oliver examines the artist's "frames and their context in Guildhall Art Gallery," while Sally Woodcock provides information about "the sources and selection of Sir John Gilbert's oil painting materials." In the Appendix, the reader may also find "Gilbert's account with his colourman, Charles Roberson & Co.," a "Technical examination of Sir John Gilbert's watercolours and oil paintings from the collection of Guildhall Art Gallery" and a "Selected list of works exhibited or sold in Gilbert's lifetime, from published sources and sketchbook references."

Having read all that, one may feel that there cannot be much left to be said about Gilbert. The painter may prove less rewarding — even though other approaches could still be imagined, regarding his historical works, for instance —, but his black and white illustrations remain an almost inexhaustible source of investigation for academics.

Bibliography

Bucklow, Spike, and Sally Woodcock, eds. Sir John Gilbert, Art and Imagination in the Victorian Age. Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2011. Hardback, 264 pp. ISBN 978-1-84822-079-9. £40.00.

Last modified 22 January 2014