Introduction: a Birmingham designer

rthur Gaskin (1862–1928) was a Midlander; born into a middle-class background in Wolverhampton in 1862 and educated at the local grammar school, his family moved to Birmingham in 1878. Gaskin entered the Birmingham School of Art in 1883, where he took a general art course and showed such promise that he was appointed to the post of assistant master before he had completed his three year course. It was here that he met and married Georgina (Georgie) Evelyn Cave French (1866–1934). Georgie became his principal collaborator, although Gaskin was also associated with his fellow members of the Birmingham School, Joseph Southall, Charles Gere and Bernard Sleigh.

Gaskin’s wide-ranging abilities as a teacher were recognised by the Principal, Edward Richard Taylor, and under his guidance began to focus on craft work, specialising in metalwork. In 1903 Gaskin became the Head of the famous School of Jewellery and Silver-smithing. He was also a jeweller working in private practice with his wife, producing necklaces and rings as well as metal pedants, boxes and other fine artefacts. These were objects in the manner of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts, and Gaskin the metal-worker was essentially a practitioner in this style.

Versatile in the manner of many of his colleagues, he was adept at other types of craft-work and enjoyed experimentation. He illustrated and designed the covers for several books in the early 1890s for mainstream and local publishers, and was ambitious to publish with the Kelmscott Press. Kelmscott was Gaskin’s inspiration and following a meeting with William Morris in 1893, whom he met in the company of Southall and Gere, went on to design the Kelmscott edition of The Shepheard’s Calendar (1896). However, this arrangement was never quite as Gaskin wished it to be. He produced illustrations for Morris’s epic fantasy, The Well at the World’s End, but his employer was dissatisfied with the images and would only publish some of them (Peterson, pp.154–158). He passed the commission to Edward Burne-Jones, and Gaskin’s career as a Kelmscott artist came to an abrupt end.

This rebuff was fairly typical of Morris’s treatment of many of his associates, and his attitude to Gaskin was always ambivalent. As William S. Peterson explains, he was ‘grateful towards Gaskin for [his] loyalty to the arts and crafts ideals, yet his praise … was often cautious and qualified’ (p.156). Morris’s reticence is clearly voiced in his ‘Introductory note’ to Gaskin’s 1895 edition of Good King Wenceslas. Having praised the value of medievalist verse and song, Morris notes that:

As this preface is a part of a book and not a criticism of it as a work of art I must not say much about the merits of the pictures done by my friend Mr, Gaskin; but I cannot help saying that they have given me very great pleasure, both as achievements in themselves and as giving hopes of a turn towards the ornamental side of illustration, which is most desirable [preface, no page number].

This seems like praise, but reads on closer inspection as a rather cool evasiveness. Morris was enthusiastic for many other projects and Peterson’s judgement seems just. Gaskin’s publications for the Kelmscott Press and other publishers are nevertheless fine examples of Arts and Crafts book design, an approach which embraced both illustration and bindings. His work is exemplified by Good King Wenceslasand S. Baring Gould’s A Book of Fairy Tales.

Gaskin as illustrator and book-cover designer

ood King Wenceslas was published in 1895 in Birmingham by the Cornish Brothers, who had earlier issued Carols (1890), a book containing several designs by Gaskin and his School of Art colleagues. This company was primarily a bookseller trading in New Street, Birmingham, where it continued until the late 1950s, and the book was probably a vanity project issued in a small imprint; Gaskin dedicated it to his wife and many of the surviving copies are inscribed with his signature. The card binding and unusual format in a size between octavo and quarto are telling marks of minority publication, and it is now extremely rare.

Left to right: (a) Page and monarch forth they went. (b) ‘Bring me flesh and bring me wine’. (c) Pictorial title-page, Book of Fairy Tales, [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Gaskin designed the illustrations, ornamental head and tail-pieces, the type-faces and the initial letters, and the covers. The illustrations were developed in the form of detailed pencil drawings, some of which can be seen in Birmingham Art Gallery, and the effect is calculatedly bespoke. Printed in bold outlines from wood-engravings and (presumably) engraved by the artist, the page surfaces are animated with a striking combination of dramatic narratives and intricate neo-medieval patterns which simultaneously recall illuminated manuscripts, incunabula, and the Kelmscott style.

The bold and dynamic illustrations are especially reminiscent of Burne-Jones’s designs for the Kelmscott Chaucer which, though not published until 1896, must surely have been seen by Gaskin before it was printed. The flat, airless space and strong figure drawing of Burne-Jones’s

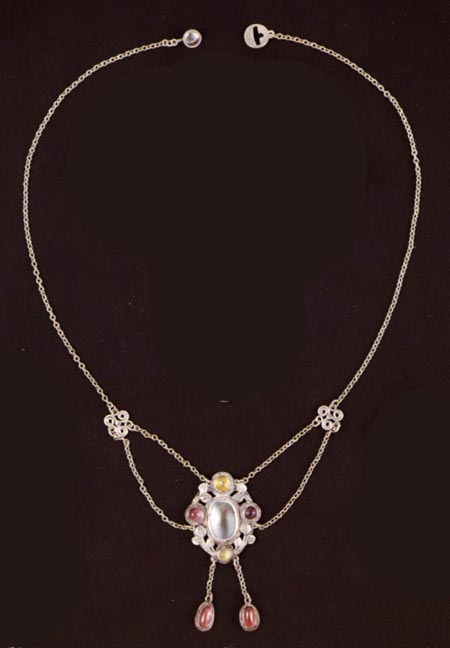

Four examples of Arthur Gaskin (1862-1928) and Georgie Gaskin jewelry work. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Art Nouveau is worth mentioning in connection with Gaskin’s book design because his imagery in some ways reflects the decorative arabesques and modernist simplicity of the emerging style of the nineties. Gaskin’s cover for Good King Wenceslas has a blunt directness which mirrors the spare bindings of Charles Ricketts. In A Book of Fairy Tales, likewise, the illustrations seem both Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau: flat, heavily blocked with strong alternations of black and white or simplified into a series of swirling, tendril-like forms, they are difficult to classify as entirely one style or the other. Indeed, the cramped picture on the front board postulates exactly this tension. It repeats the illustration on the title-page, but places it off-centre; at once a piece of image-making that would not be incongruous in one of Morris’s editions, its asymmetrical arrangement provocatively suggests the sophistication of covers by Aubrey Beardsley and Laurence Housman.

Primarily a practitioner of three-dimensional crafts in the form of metalwork and jewellery, Gaskin is nevertheless an interesting contributor to the development of late Victorian book-art. Largely overlooked, his publications quirkily combine the traditions of craft-work and mass-production, the provincial and the international, the distinctly English and home-made, and the suggestion of a wider cultural reference. In these ways his books closely mirror the character of Britain’s second city as it was in the nineteenth century, and as it remains today.

Works Cited

Book of Fairy Tales, A. Re-told by S. Baring Gould. Illustrations and binding by Arthur Gaskin. London: Methuen, 1894.

Good King Wenceslas: A Carol Written by Dr Neale and Pictured by Arthur J Gaskin with an Introduction by William Morris. Birmingham: Cornish Brs. 1895.

Peterson, William S. The Kelmscott Press: A History of William Morris’s Typographical Adventure. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Last modified 6 January 2014