Doctor Marigold's Little Visitor

Harry Furniss

1910

13.8 x 8.8 cm vignetted

Dickens's Christmas Stories, Vol. XVI of The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing page 496.

The 1865 Christmas framed tale Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions contains Dickens's introduction and conclusion, as well as his contribution to the material within the frame, the independent short story "To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt" (since reprinted in Two Ghost Stories as "The Trial for Murder") — and further extraneous material by his lesser staff-writers at All the Year Round as the stories that her adoptive father writes for the deaf-and-dumb child. [Commentary continued below.]

[Click on image to enlarge it, and mouse over to find links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

I am a neat hand at cookery, and I'll tell you what I knocked up for my Christmas-eve dinner in the Library Cart. I knocked up a beefsteak-pudding for one, with two kidneys, a dozen oysters, and a couple of mushrooms thrown in. It's a pudding to put a man in good humour with everything, except the two bottom buttons of his waistcoat. Having relished that pudding and cleared away, I turned the lamp low, and sat down by the light of the fire, watching it as it shone upon the backs of Sophy's books.

Sophy's books so brought Sophy's self, that I saw her touching face quite plainly, before I dropped off dozing by the fire. This may be a reason why Sophy, with her deaf-and-dumb child in her arms, seemed to stand silent by me all through my nap. I was on the road, off the road, in all sorts of places, North and South and West and East, Winds liked best and winds liked least, Here and there and gone astray, Over the hills and far away, and still she stood silent by me, with her silent child in her arms. Even when I woke with a start, she seemed to vanish, as if she had stood by me in that very place only a single instant before.

I had started at a real sound, and the sound was on the steps of the cart. It was the light hurried tread of a child, coming clambering up. That tread of a child had once been so familiar to me, that for half a moment I believed I was a-going to see a little ghost.

But the touch of a real child was laid upon the outer handle of the door, and the handle turned, and the door opened a little way, and a real child peeped in. A bright little comely girl with large dark eyes.

Looking full at me, the tiny creature took off her mite of a straw hat, and a quantity of dark curls fell about her face. Then she opened her lips, and said in a pretty voice,

"Grandfather!"

"Ah, my God!" I cries out. "She can speak!" [Chapter II, "To Be Taken Life," pp. 495-496]

Commentary

Thus, the multi-part story as it originally appeared on 12 December 1865 was a collaborative effort by the "Conductor" and Dickens's staff-writers, who produced five of Doctor Marigold's "prescriptions" or stories that he provides for the second Sophy. Irish writer Rosa Mulholland (1841-1921) contributed "Not To Be Taken at Bed-Time"; Dickens's son-in-law, painter and writer Charles Allston Collins, "To Be Taken at the Dinner-Table"; children's writer Hesba Stretton (the nom de plume of Sarah Smith, 1832-1911), "Not To Be Taken Lightly"; novelist and journalist Walter Thornbury (1828-1876), "To Be Taken in Water"; and Mrs. Gascoyne (probably the obscure novelist Caroline Leigh Smith, 1813-1883), "To Be Taken and Tried." Only the three chapters that Dickens contributed appear in the 1868 Illustrated Library Edition, the British and American Household Editions of the 1870s, and the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition. However, whereas the 1868 edition places Dickens's second contribution, "To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt" (subsequently dissociated from its original context and retitled "The Trial for Murder") before the third, the 1910 edition appends what was originally the sixth chapter in the 1865 novella. Editors of both of the Household Edition volumes have simply inserted "The Trial for Murder" after the Marigold sequence as one of "Two Ghost Stories."

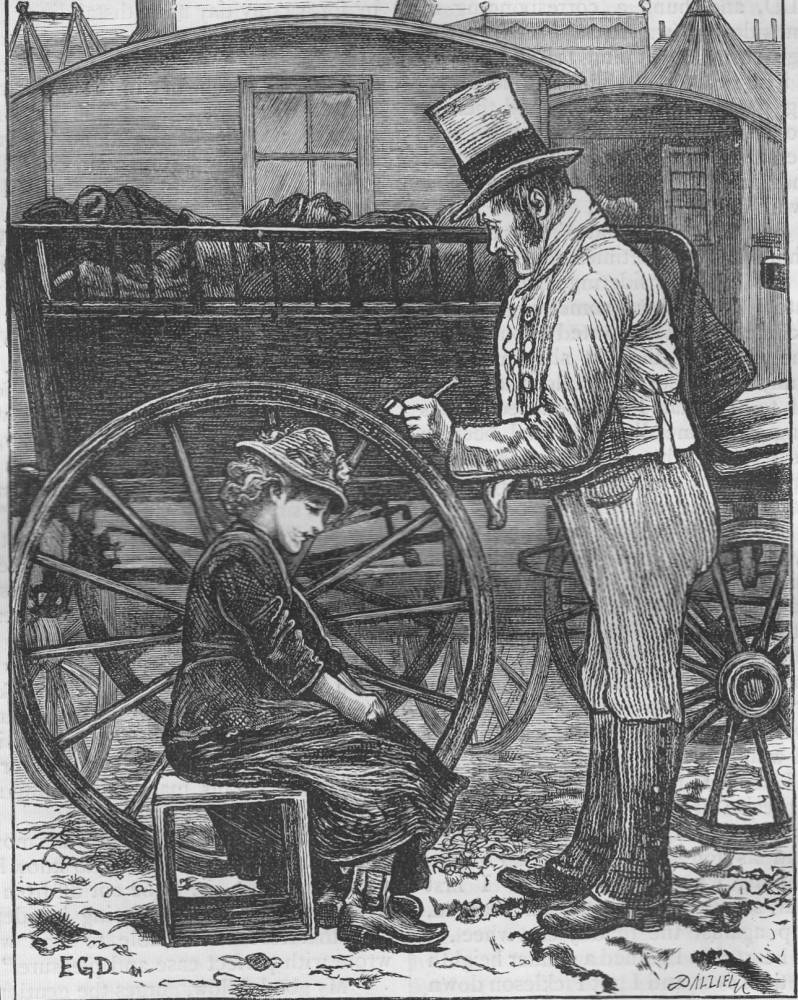

The Illustrated Library Edition's "anthologized" version of the 1865 novella contains Edward Dalziel's Doctor Marigold. The 1876 American Household Edition of Christmas Stories contains E. A. Abbey's sixties style illustrations for The Christmas Books and plates for a few of the periodical stories, including the charming realisation of the visit by Sophy's daughter, "Grandfather!". Edward Dalziel was Chapman and Hall's choice of illustrator for its own Household Edition volume the following year; his execution of the illustration And at last, sitting dozing against a muddy cart-wheel, I come upon the poor girl who was deaf and dumb for this chapter, although hardly as dynamic as Furniss's pencil-and-ink sketch of Doctor Marigold teaching his adopted daughter how to read, does at least (if somewhat unemotionally and statically) explore the physical dimensions of cheap jack and the child, and effectively presents the waggon. Furniss seems to have felt that the Doctor Marigold Christmas story was among the more significant in the two decades of seasonal offerings, for whereas he did not even illustrate The Perils of Certain English Prisoners (1857, Household Words), he provided three illustrations for the Marigold framed-tales, yet only one, for example, for the "two-season" Lirriper stories.

Dalziel's illustration entitled Doctor Marigold in the 1868 Illustrated Library Edition realizes the moment at which protagonist first meets the deaf-and-dumb child whom Providence provides in place of his own daughter, victim of prolonged abuse at the hands of his demented wife, whereas E. A. Abbey's realizes the touching passage in which Dickens describes through the persona of the aged cheap jack the return from China of the second Sophy, now a wife and mother, and her daughter. Significantly, only Doctor Marigold and the granddaughter appear in the illustrations of Abbey and Furniss, whereas in the Illustrated Library Edition Dalziel includes a grownup "daughter of empire" in the frame. Moreover, this Dalziel illustration, although realizing the climactic reunion at the close of what was originally part seven, is positioned only eight pages into part one, compelling a proleptic reading that only reference to this illustration thirty-seven pages later will complete.

Relevant Illustrated Library Edition (1868) and Household Edition (1876-77) Illustrations

Left: E. G. Dalziel's 1868 plate "Doctor Marigold". Centre: E. A. Abbey's "Grandfather!". Right: Edward Dalziel's 1877 illustration "And at last, sitting dozing against a muddy cart-wheel, I come upon the poor girl who was deaf and dumb." [Click on images to enlarge them.]

From its position in the text, the 1868 Dalziel illustration would appear to concern Doctor Marigold, the first Sophy (clinging to him for protection), and young Suffolk wife; closer examination of the reflective and tranquil scene reveals the book-lined walls, which in turn suggest that this scene is comparable to Abbey's realisation of the return. Here, Furniss provides his own version of the reunion realised by Abbey and Dalziel in Dr. Marigold's Little Visitor. In contrast to the pensive stillness of this first Dalziel illustration (which does not reveal that Sophy's child is capable of speech) and the delighted surprise of Grandfather Marigold in his book-lined cart as his grand-daughter rushes in, Furniss presents the moment as overflowing with sentimentality as the lonely cheap jack, in meeting his granddaughter for the first time, is delighted to discover that she can speak, and that therefore Sophy's disability is not an inheritable tendency.

Since he was intimately familiar with Dickens's life through John Forster's biography of his favourite author, Furniss would have recognised through his extensive reading of the Dickens canon that depictions of children and young adults afflicted with complete deafness (aside from the stock stage figure of the aged man who, having become hard of hearing, must carry an ear-trumpet, a figure such as The Aged P in Dickens's Great Expectations) are rare in Victorian fiction, and that Sophy breaks type in going away to school and herself becoming a parent, despite societal apprehensions that such a dysfunction could be genetic. Dickens clearly comes down on The side of the progressives in such matters, arguing through the character of Sophy's daughter that visual and hearing impairments are not necessarily genetically transmitted.

Until the grandchild addresses him as "Grandfather," neither he nor the reader knows that she can speak, for Sophy had written that she feared her daughter was deaf and dumb. Thus, in Abbey's version of the scene, the proleptic reading facilitated by the illustration partially undercuts the suspense as the reader is alerted to the fact, even before starting the story, that the child is capable of speech. Perhaps believing that many Household Edition readers would be familiar with the ten-year-old story, Abbey has chosen to reveal the climax even before the story begins, exciting a certain interest as to how the narrative will arrive at this sentimental climax, foreshadowed in one of the volume's three full-page illustrations. Conversely, Furniss realises the scene without much contextualising detail (the books are just lightly sketched in; the stove and the grandchild's mother and father, all specifically alluded to in the text, are simply to be imagined by the reader), but juxtaposes the pen-and-ink drawing with the text facing. In other words, the reader encounters the text and its illustration more or less at the same time, so that the Impressionistic illustrator felt free to focus on the emotions of the two key figures immediately following the climactic moment.

Significantly, while Abbey has chosen to depict the suspenseful moment as Sophy's daughter enters the library cart and Droctor Marigold turns around upon hearing a child's footsteps outside, Furniss has chosen the moment afterward, so that his emphasis is upon Doctor Marigold's joyful welcome of the little visitor, rather than on the plot secret. The composition places the heads of the grandfather and granddaughter just above centre, and balances the diminutive figure with her straw hat, discarded in haste upon the floor. The carter's leggings, symbolic of his itinerant lifestyle, likewise balance his capacious chair, suggestive of his desire for comfort and family in his old age.

Editor J. A. Hammerton adds the following footnote at the conclusion and immediately prior to Chapter III, "To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt":

[Dickens wrote three chapters of "Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions." To preserve the effect of the story, two of these chapters have here been transposed. The following was Chap. vi. of the original, and "To be Taken for Life" was the concluding chapter of the series. Ed.]

Hammerton thus begs the question, "What was the effect of the original, unillustrated sequence for readers of December 1865? Were the productions of Dickens's staffers really so second-rate that they no longer deserve a reading in order to maintain the original sequence of "prescriptions"? The narrative voice in the Charles Dickens Library Edition shifts abruptly away from the racey verbosity of the King of the Cheap Jacks towards the measured cadences of an educated speaker, so appropriate to foiling the sensational material of the ghost story, unaccompanied by illustration and left to speak for itself without visual comment.

Bibliography

Archibald, Diana. "Laura Bridgman and Marigold's Sophie: The Influence of the Perkins Visit on Dickens." Dickens Society of America Symposium. Victoria College, University of Toronto. 5 July 2013.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 16.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All The Year Round." Illustrated by Fred Walker, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, E. G. Dalziel, J. Mahony [sic], Townley Green, and Charles Green. Centenary Edition. 36 vols. London: Chapman & Hall; New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911. Vol. II.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Edward Dalziel, Harry French, F. A. Fraser, James Mahoney, Townley Green, and Charles Green. The Oxford Illustrated Dickens. Oxford, New York, and Toronto: Oxford U. P., 1956, rpt. 1989.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 19 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Vol. III.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round." Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. Rpt., 1892. Vol. XXI.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. "Christmas Stories." The Oxford Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 100-101.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

Harry

Furniss

Next

Created 22 September 2013