A Christmas Tree

Harry Furniss

1910

13.8 x 8.9 cm (framed)

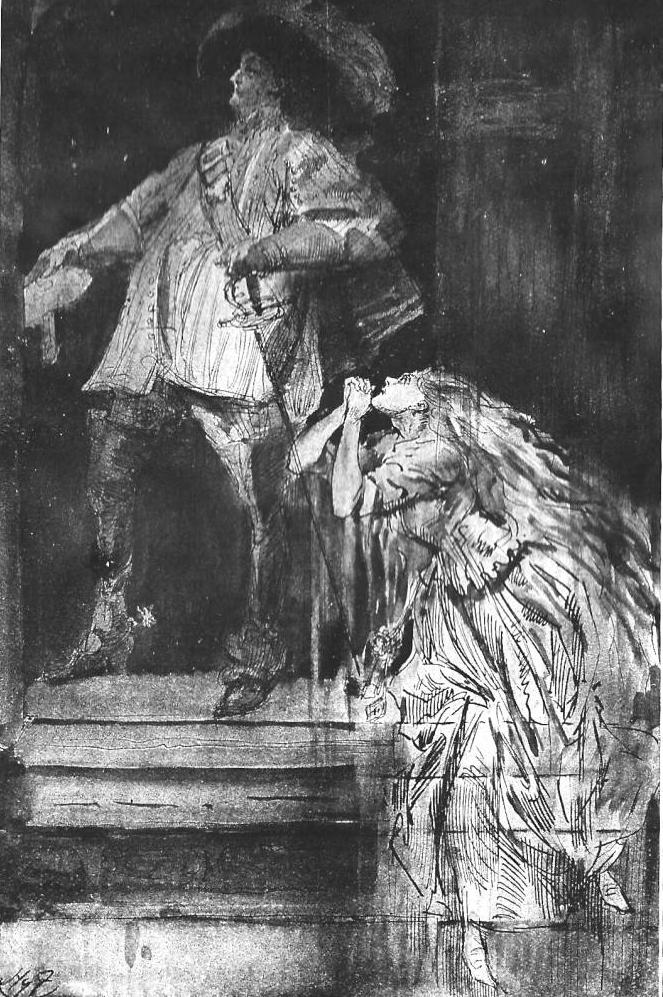

Dickens's Christmas Stories, Vol. XVI of Charles Dickens Library Edition, frontispiece.

Again, as in "Captain Murderer" in "Nurse's Stories," one of the essays appearing in The Uncommercial Traveller, Dickens reveals his abiding interest in tales of horror and the supernatural in this, his chief contribution to the initial Christmas number of his recently launched weekly journal Household Words, although the clicheéd scenario involving an anxious nobleman in the haunted room of a great country house is merely a long paragraph in a personal essay on the joys of the Christmas season, and does not constitute a short story or even a sketch in the Victorian sense. [Commentary continued below.]

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

There is probably a smell of roasted chestnuts and other good comfortable things all the time, for we are telling Winter Stories — Ghost Stories, or more shame for us — round the Christmas fire; and we have never stirred, except to draw a little nearer to it. But, no matter for that. We came to the house, and it is an old house, full of great chimneys where wood is burnt on ancient dogs upon the hearth, and grim portraits (some of them with grim legends, too) lower distrustfully from the oaken panels of the walls. We are a middle-aged nobleman, and we make a generous supper with our host and hostess and their guests — it being Christmas-time, and the old house full of company — and then we go to bed. Our room is a very old room. It is hung with tapestry. We don't like the portrait of a cavalier in green, over the fireplace. There are great black beams in the ceiling, and there is a great black bedstead, supported at the foot by two great black figures, who seem to have come off a couple of tombs in the old baronial church in the park, for our particular accommodation. But, we are not a superstitious nobleman, and we don't mind. Well! we dismiss our servant, lock the door, and sit before the fire in our dressing-gown, musing about a great many things. At length we go to bed. Well! we can't sleep. We toss and tumble, and can't sleep. The embers on the hearth burn fitfully and make the room look ghostly. We can't help peeping out over the counterpane, at the two black figures and the cavalier — that wicked-looking cavalier — in green. In the flickering light they seem to advance and retire: which, though we are not by any means a superstitious nobleman, is not agreeable. Well! we get nervous — more and more nervous. We say "This is very foolish, but we can't stand this; we'll pretend to be ill, and knock up somebody." Well! we are just going to do it, when the locked door opens, and there comes in a young woman, deadly pale, and with long fair hair, who glides to the fire, and sits down in the chair we have left there, wringing her hands. Then, we notice that her clothes are wet. Our tongue cleaves to the roof of our mouth, and we can't speak; but, we observe her accurately. Her clothes are wet; her long hair is dabbled with moist mud; she is dressed in the fashion of two hundred years ago; and she has at her girdle a bunch of rusty keys. Well! there she sits, and we can't even faint, we are in such a state about it. Presently she gets up, and tries all the locks in the room with the rusty keys, which won't fit one of them; then, she fixes her eyes on the portrait of the cavalier in green, and says, in a low, terrible voice, "The stags know it!" After that, she wrings her hands again, passes the bedside, and goes out at the door. We hurry on our dressing-gown, seize our pistols (we always travel with pistols), and are following, when we find the door locked. We turn the key, look out into the dark gallery; no one there. ["A Christmas Tree — Christmas Ghosts," pp. 582-3]

Commentary

The gentle reverie well conjures up the tone and mood of those enormously popular "extra" numbers of 24 pages, which expanded to 36 and finally 48 pages, and achieved sales of some 300,000 copies, but does not appear in chronological sequence in the Furniss volume, but eighteenth, although it was the first of Dickens's post-Christmas Books (1843-48).

First published in the initial Christmas number of Household Words in 1850, the imaginative (albeit somewhat satirical) scenario for a Blackwood's tale of terror and the supernatural,reflects Dickens's adolescent reading. The mature writer's recollection of the fireside telling of such ghost stories in youth is triggered by the smell of roasting chestnuts, but in other respects the brief story is visual and tactile in nature:

in this cinematic sketch of a thoughtful observer's shifting thoughts, Dickens has provided a glimpse into the workings of imagination as well as the toys, books, theatrical productions, fairy tales, and tales of the uncanny, which — as his earlier writings indicate — he viewed as the vital childhood roots of this imaginative realm. [Thomas, p. 71]

The frontispiece in a series such as the sixteen-volume Charles Dickens Library must serve several different functions, alerting the reader to the general nature of the material in the volume, but also preparing the reader for a specific moment in the text, as well as standing alone as a work of art whose composition and colouration or shading render it worthy of consideration without reference to any single passage in the text. That this dark plate, in the manner of Phiz in Bleak House accomplishes all of these purposes in some measure shows Furniss's calibre as an illustrator. However, the reader (until he or she actually arrives at the passage realised hundreds of pages later) probably does not distinguish between the portrait of the seventeenth-century cavalier and the ghost of the bride, even though the line separating the two halves of the illustration suggests the former while the horizontal lines (lower right), continuing through the dress and the bride's feet imply her insubstantial nature. The lithograph of the pen-and-ink study has the added novelty of illustrating a passage not heretofore attempted by even the Household Edition illustrators E. A. Abbey and Edward Dalziel. The first anthologized printing of "A Christmas Tree" in the volume issued by Chapman and Hall as Christmas Stories in 1859 had no illustrations whatsoever, but the Ticknor and Fields Diamond Edition volume of 1867 has the customary eight full-page wood-engravings by Sol Eytinge, Jr. TheChapman and Hall single-volume edition of the Christmas Stories(1871) contains eight illustrations by various artists, pictures to which Furniss would definitely have had access and which the Oxford Illustrated Dickens elected to use in prference to Edward Dalziel's 1877 Household Edition illustrations.

In some respects, Furniss's choice of subject matter for the frontispiece is misleading to a reader not familiar with the Christmas Stories originally published in Dickens's weekly journals Household Words (1850-58) and All the Year Round (1859-67). The majority of these twenty-three selections are not tales of the supernatural (the exception being the framed tale The Haunted House), but rather highly varied tales of a convivial, seasonal nature involving endearing characters such as Richard Doubledick, the Boy at Mugby Junction, Mrs. Lirriper, Dr. Marigold, and Cobbs, the Boots at the Holly Tree Inn. The framed tales, "framed" by Dickens and then completed by such writers as Elizabeth Gaskell and Wilkie Collins, consistently involve memory, nostalgia, romance, sentimentality, and occasionally suspense, melodrama, and character comedy. Perhaps Furniss is suggesting the jovial tone of the reminiscing narrator of "Christmas Ghosts" in "A Christmas Tree" through the adoring look and gentle smile on the face of the bride-ghost, who is as benign as any of the spirits in The Christmas Books of the 1840s. Stupendously popular in both the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1850s and 1860s, these framed tales, beginning with "The Poor Relation's Story" in 1852, were by the end of the century indeed "Ghosts of Christmas."

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. XVI.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Edward Dalziel, Harry French, F. A. Fraser, James Mahoney, Townley Green, and Charles Green. The Oxford Illustrated Dickens. Oxford, New York, and Toronto: Oxford U. P., 1956, rpt. 1989.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 19 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Vol. III.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. Rpt., 1892. Vol. XXI.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. "Christmas Stories." The Oxford Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 100-101.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

Harry

Furniss

Next

Created 14 August 2013

Last modified 18 August 2025