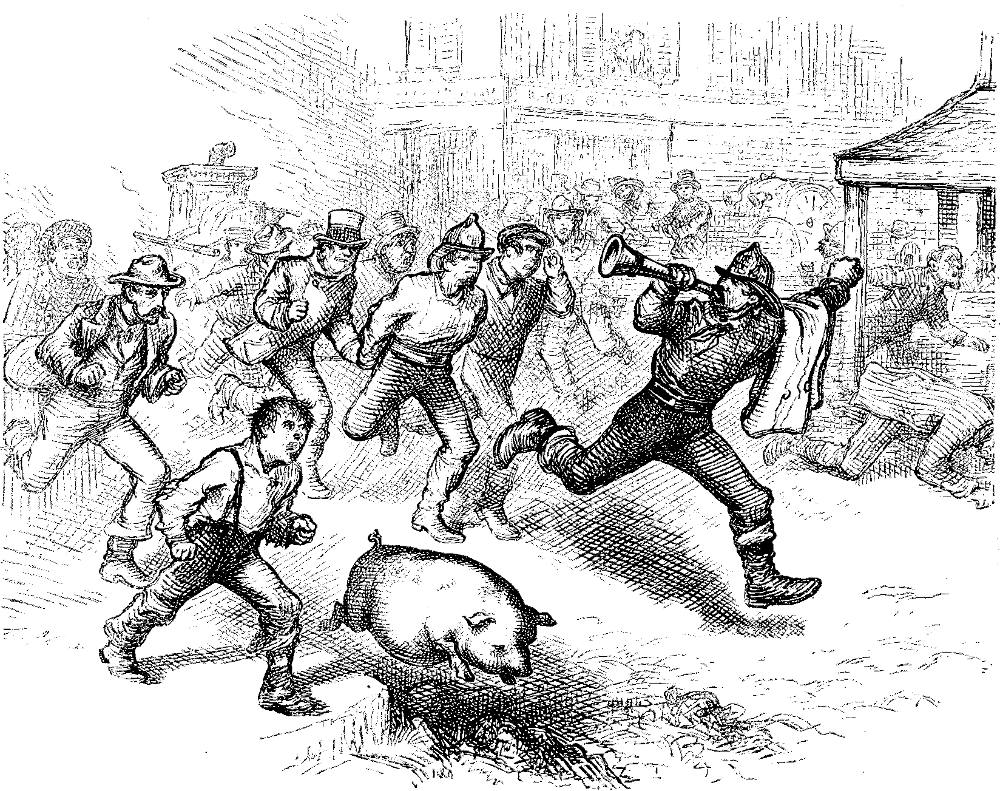

When suddenly the lively hero Dashes in to the Rescue by A. B. Frost (engraved by Edward G. Dalziel), in Charles Dickens's Pictures from Italy and American Notes (1880), Chapter VI, "New York," facing p. 277. Wood-engraving, 3 ⅞ by 5 ½ inches (9.9 cm high by 13.4 cm wide), framed. This theatrical passage offers a light-hearted to Dickens's visit to New York City's Tombs (the municipal jail) and an asylum for the insane. Frost seems to have drawn his study of the exuberant dancers from life, as Dickens offers little background detail about the saloon, ands mentions only a single virtuoso dance performance.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realized: An Exuberant Dance in a Five-Points Saloon

The corpulent black fiddler, and his friend who plays the tambourine, stamp upon the boarding of the small raised orchestra in which they sit, and play a lively measure. Five or six couple come upon the floor, marshalled by a lively young negro, who is the wit of the assembly, and the greatest dancer known. He never leaves off making queer faces, and is the delight of all the rest, who grin from ear to ear incessantly. Among the dancers are two young mulatto girls, with large, black, drooping eyes, and head-gear after the fashion of the hostess, who are as shy, or feign to be, as though they never danced before, and so look down before the visitors, that their partners can see nothing but the long fringed lashes.

But the dance commences. Every gentleman sets as long as he likes to the opposite lady, and the opposite lady to him, and all are so long about it that the sport begins to languish, when suddenly the lively hero dashes in to the rescue. Instantly the fiddler grins, and goes at it tooth and nail; there is new energy in the tambourine; new laughter in the dancers; new smiles in the landlady; new confidence in the landlord; new brightness in the very candles.

Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man’s fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs — all sorts of legs and no legs — what is this to him? And in what walk of life, or dance of life, does man ever get such stimulating applause as thunders about him, when, having danced his partner off her feet, and himself too, he finishes by leaping gloriously on the bar-counter, and calling for something to drink, with the chuckle of a million of counterfeit Jim Crows, in one inimitable sound! [Chapter VI, "New York," pp. 274-275]

Commentary: The Beginnings of the Broadway Musical in Lower Manhattan

Dickens mentions only three New York theatres: the Park, the Bowery, and the Olympic. Only the third, he notes, has much of an audience, probably because it alone features such popular entertainments as vaudevilles and burlesques. He also mentions a strictly seasonal theatre, Niblo's, as sharing the malaise of the two legitimate houses. Ironically, as A. B. Frost, working on the illustrations for the Household Edition in the 1870s would have appreciated, this underutilised, underpatronised summer theatre from the 1840s would become the 3,200-sea venue for the first Broadway musical, The Black Crook, which opened on 12 September 1866, and ran for 474 performances on Broadway. The dramatic dance that Dickens describes seems to anticipate what would twenty years later become the Broadway Musical. However, the animated performance which Dickens describes possesses only the choreography and live orchestra of such a large-cast show, and apparently has no libretto. Moreover, it is staged not in a theatre on Broadway, but in a saloon at the Five Points, then an overpopulated and largely Negro slum in Lower Manhattan. Dickens whimsically describes Almack's Saloon as "the assembly-room of the Five-Point fashionables" (274).

The illustrator describes the scene from the perspective of the musicians, for his vantage-point is immediately behind the blind fiddler. Although it is a Black establishment and majority of the patrons as well as the performers are Black, two of the patrons are the bar (perhaps intended to represent Dickens and his guide) are middle-aged whites in respectable topcoats and top-hats. But Frost has made the two male dancers the focal characters.

A quite different New York scene from the American Household Edition (1877)

Above: Thomas Nast's lively street scene in which a fire crew races through New York's streets on foot, "Fire! Fire!" (1877).

Related Material

- Charles Dickens, the traveler — places he visited

- Charles Dickens, 1843 daguerrotype by Unbek in America; the earliest known photographic portrait of the author

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Chapter IV, "An American Railroad. Lowell and Its Factory System." American Notes. Illustrated by A. B. Frost; engraved by Edward G. Dalziel. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880. Pp. 245-53.

Last modified 12 March 2019