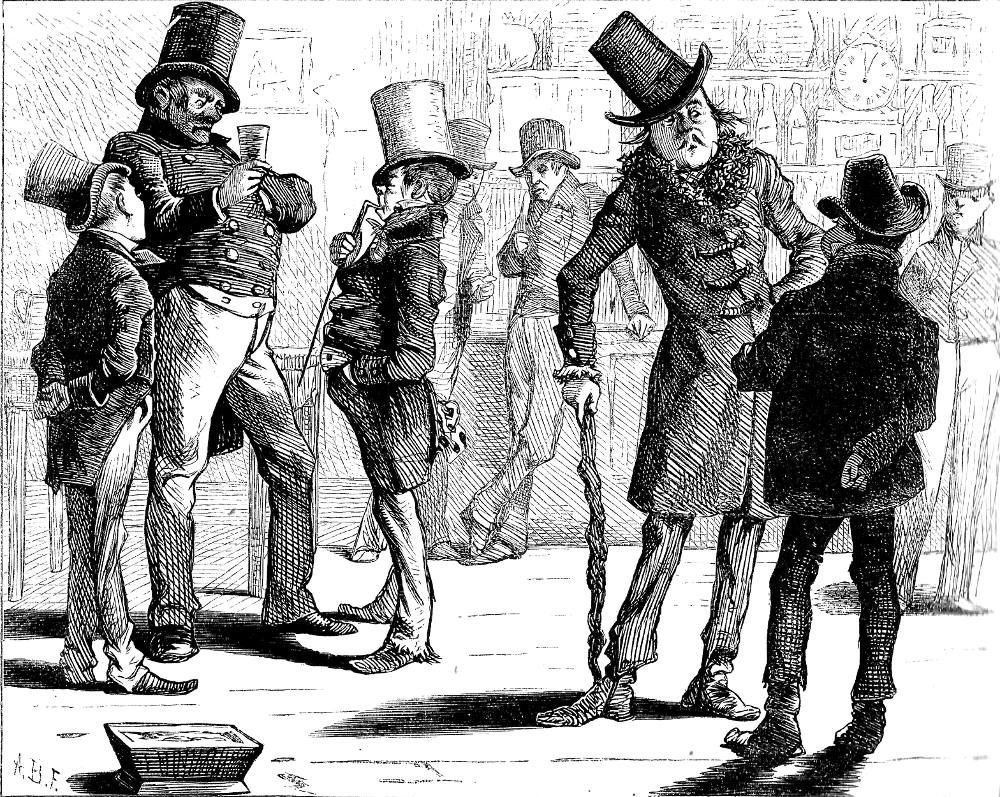

See them at the neighbouring public-house in Chapter XIII of "Scenes" — "Private Theatres," in Dickens's Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People (1877), middle of page 134. Wood-engraving; 4 ⅛ by 5 ¼ inches (10.5 cm high by 13.3 cm wide), framed. Frost had not seen a London theatre, either amateur or professional, until he visited London in 1877. The article entitled "Private Theatres" originally appeared as "Sketches of London No. 19" in The Evening Chronicle on 11 August 1835, under the pseudonym "Boz," which Dickens had been using in that journal since August 1834.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: A Post-Performance Interlude

These gentlemen are the amateurs — the Richards, Shylocks, Beverleys, and Othellos — the Young Dorntons, Rovers, Captain Absolutes, and Charles Surfaces — a private theatre.

See them at the neighbouring public-house or the theatrical coffee-shop! They are the kings of the place, supposing no real performers to be present; and roll about, hats on one side, and arms a-kimbo, as if they had actually come into possession of eighteen shillings a-week, and a share of a ticket night. If one of them does but know an Astley’s supernumerary he is a happy fellow. The mingled air of envy and admiration with which his companions will regard him, as he converses familiarly with some mouldy-looking man in a fancy neckerchief, whose partially corked eyebrows, and half-rouged face, testify to the fact of his having just left the stage or the circle, sufficiently shows in what high admiration these public characters are held.

With the double view of guarding against the discovery of friends or employers, and enhancing the interest of an assumed character, by attaching a high-sounding name to its representative, these geniuses assume fictitious names, which are not the least amusing part of the play-bill of a private theatre. Belville, Melville, Treville, Berkeley, Randolph, Byron, St. Clair, and so forth, are among the humblest; and the less imposing titles of Jenkins, Walker, Thomson, Barker, Solomons, &c., are completely laid aside. There is something imposing in this, and it is an excellent apology for shabbiness into the bargain. A shrunken, faded coat, a decayed hat, a patched and soiled pair of trousers — nay, even a very dirty shirt (and none of these appearances are very uncommon among the members of the corps dramatique), may be worn for the purpose of disguise, and to prevent the remotest chance of recognition. Then it prevents any troublesome inquiries or explanations about employment and pursuits; everybody is a gentleman at large, for the occasion, and there are none of those unpleasant and unnecessary distinctions to which even genius must occasionally succumb elsewhere. As to the ladies (God bless them), they are quite above any formal absurdities; the mere circumstance of your being behind the scenes is a sufficient introduction to their society—for of course they know that none but strictly respectable persons would be admitted into that close fellowship with them, which acting engenders. They place implicit reliance on the manager, no doubt; and as to the manager, he is all affability when he knows you well, — or, in other words, when he has pocketed your money once, and entertains confident hopes of doing so again. ["Scenes," Chapter XIII, "Private Theatres," pp. 134-135 ]

Commentary: Amateurs taking themselves Seriously

The characters in the frame only approximately correspond to the gentlemen-actors whose amateur status Boz describes in "Private Theatres." Although he includes seven named parts from Richard the Third in the headnote, delineating what each amateur will receive for his performance, eight amateurs engage in phlegmatic conversations in the public house near the theatre after the performance. The tall, stout man who dominates the left-hand register is evidently the moldy-looking actor in a fancy neckerchief who has partially corked eyebrows and a rouged face, but Frost has omitted the "fancy neckerchief" entirely, and nobody in his picture has his arms akimbo in self-confident swagger. However, the crowed communicates the sense of Boz's off-duty thespians, and the setting of the clock at five past midnight suggests a post-performance gathering in the "little stage-struck neighborhood" (134) that young Dickens himself as an aspiring actor once frequented.

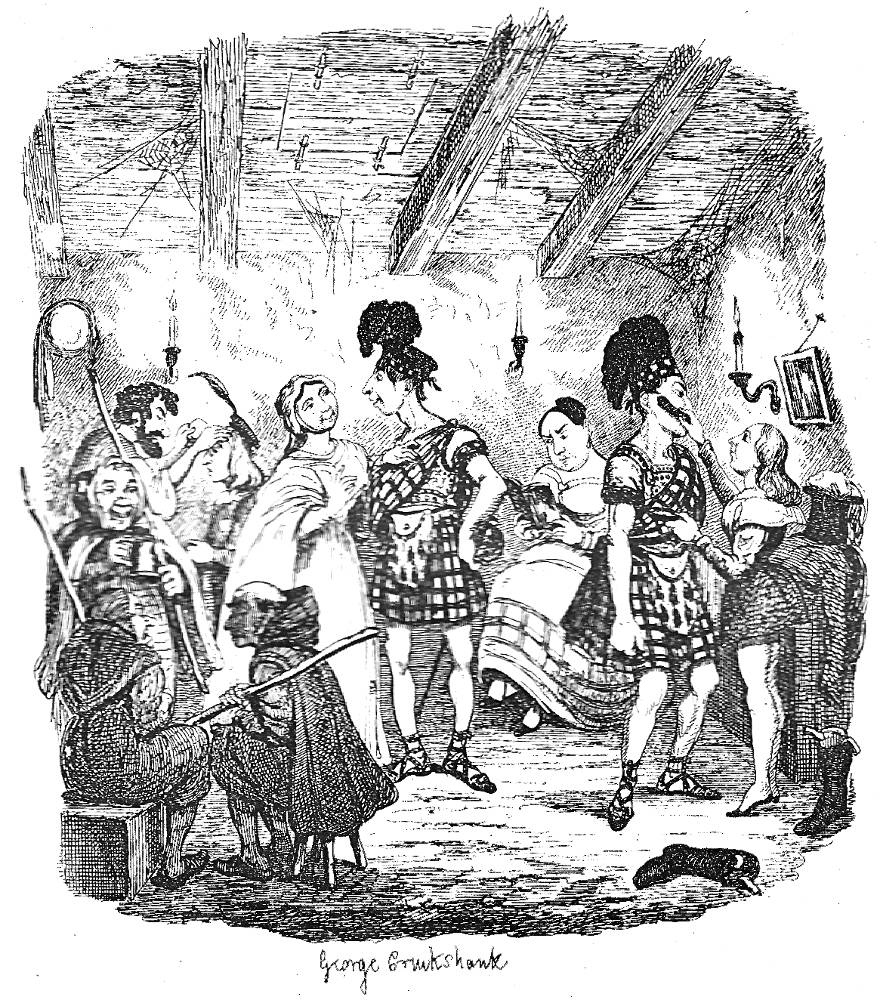

Since the licensing regulations in Great Britain did not apply to private theatres, such places were free to do Shakespeare, even if they did it badly. One can see in the original Cruikshank illustration the cramped area under stage that serves as the Green Room. Frost takes a very different approach, studying the actors as they meet after the performance at a local public house to discuss the evening's performance; but, again, they are assuming roles, not of characters from the popular drama, but of professional actors.

Until 1875 theatres were the chief form of entertainment for Londoners of all social classes, and Dickens as a young man knew the theatres of The City (central London) extremely well, even agreeing (in the months prior to his bursting on the literary scene as "Boz") to an audition which he was fortuitously compelled to cancel because of a head cold. That was in March 1832, when the twenty-year-old law clerk, hoping to begin a career on the stage, had written to George Bartley, the manager of the Covent Garden Theatre.

As a young New Yorker, A. B. Frost would have been familiar with the limited theater scene there: the eighteenth-century playhouses at John Street and Nassau Street, and the far more commodious Park Theatre, which opened in 1798. Like Dickens, he would probably have visited the Bowery, but not the same Niblo's as impressario William Niblo's Garden Theatre that Dickens had visited in 1842 and which burned down seven years later. (Since it had been re-built on the same site, Frost patronized an entirely different Niblo's.) With sufficient "legitimate" playhouses (as well as countless saloon venues), New York City had little need of the amateur houses that London boasted in such numbers, so that the cultural as well as the theatrical context of this chapter in "Scenes" would have been very different for the two Household Edition illustrators, Frost and Barnard.

Related Material

Relevant Illustrations from the Chapman & Hall (1837-39) and Household Editions (1876)

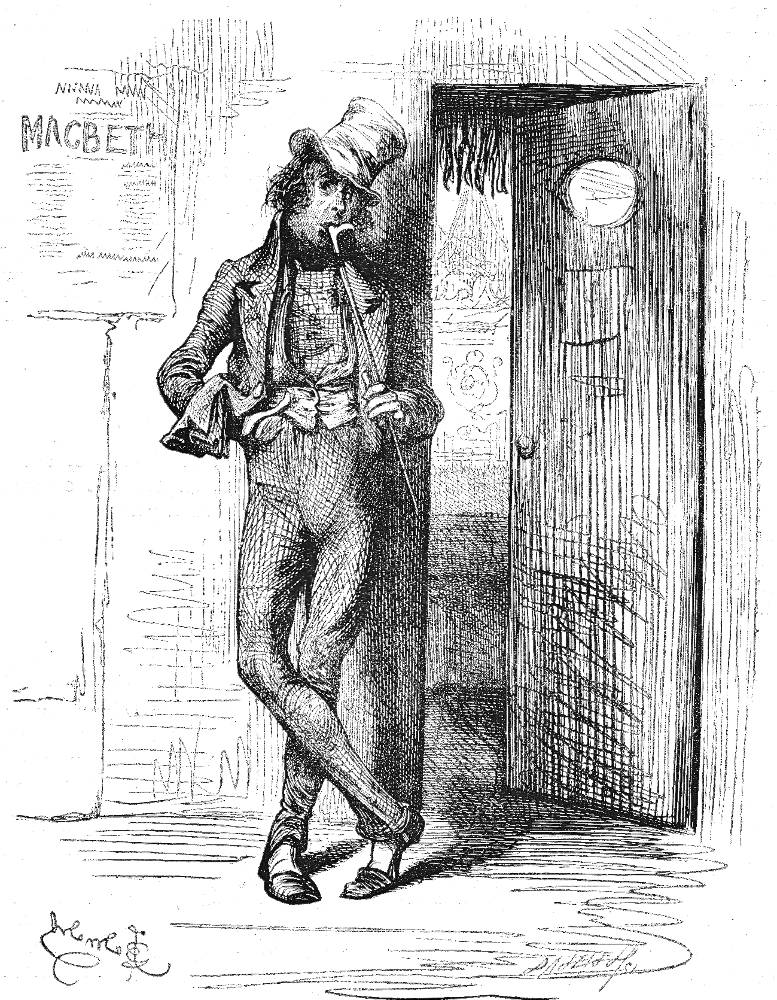

Left: The original George Cruikshank illustration of an amateur production of Macbeth in Amateur Theatres. Right: Fred Barnard's realistic character study of an amateur comedian for the same sketch, His line is genteel comedy — his father's coal and potato. He does Alfred Highflier in the last piece, and very well he'll do it — at the price (vignette for the British Household Edition).

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Private Theatres," Chapter 13 in "Scenes." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1836; rpt., 1890. Pp. 88-92.

Dickens, Charles."Private Theatres," Chapter 13 in "Scenes." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. XIII, 56-59.

Dickens, Charles. "Private Theatres," Chapter 13 in "Scenes." Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz and American Notes. Illustrated by Thomas Nast and Arthur B. Frost. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1877 (copyrighted in 1876). Pp. 133-36.

Dickens, Charles. "Private Theatres," Chapter 13 in "Scenes." Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People. Ed. J. A. Hammerton. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. I, 112-18.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hartnoll, Phyllis. The Oxford Concise Companion to the Theatre. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1972.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall,1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp.1-28.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 17 June 2019